Shining a gaslight on ‘what women go through’ No known cause or cure and often dismissed and misdiagnosed, endometriosis leaves many women immobilized by pain and isolation

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/12/2023 (713 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When Ashley Gobeil was 15 years old, she began to experience incredibly painful periods.

“Like bleed-through-a-tampon-in-two-minutes, on the floor in the fetal position the first few days of every menstruation,” says Gobeil, now 41.

Silenced Symptoms

Downplayed. Dismissed. Devalued.

In this monthly Free Press series, we’ll explore underdiagnosed, underrecognized and undertreated health issues affecting the lives of women, nonbinary and trans people. We will share stories and lived experiences, while also raising awareness.

In this instalment, we look at endometriosis.

Her friends would stare at her open-mouthed when she told them how often she had to change her tampons; Gobeil, meanwhile, couldn’t believe they could keep theirs in all day. The pain began keeping her from school. Suspecting something was very wrong, Gobeil went to her doctor who told her what she was experiencing was normal, and to take a Tylenol.

“This was the beginning of how gaslit and dismissed I was trying to get answers about my own health at age 15,” she says.

It would be another 13 years — along with two high-risk pregnancies resulting in two premature babies and bleeding throughout all of it — before Gobeil would get diagnosed with endometriosis at the age of 28.

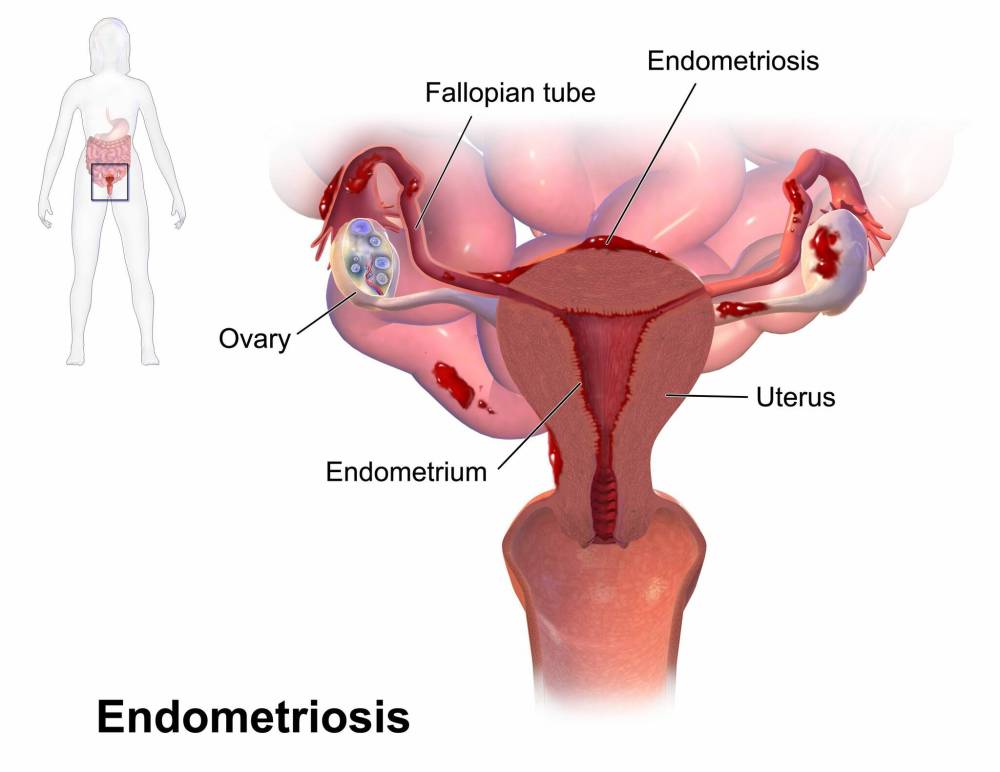

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory disease in which tissue that looks and behaves similarly to the lining of the uterus grows outside the uterus.

This tissue is most often found on or around reproductive organs in the pelvis or abdomen such as the ovaries, fallopian tubes and the surface of the uterus. It can also grow on or around other organs, such as the intestines, rectum or bladder.

The tissue responds to hormones as the tissue inside the uterus does, but because it doesn’t shed during a menstrual cycle, it can bleed, become inflamed and cause scarring. This can cause debilitating, life-altering pain — during menstruation, during ovulation, during or after sexual intercourse, during urination and/or bowel movements — as well as heavy bleeding, nausea, bloating, fatigue and infertility.

“If you have painful periods, you’re more likely to have endometriosis than to not have endometriosis.”– Dr. Devon Evans, a Winnipeg-based OB/GYN who specializes in endometriosis and pelvic pain

Endometriosis affects an estimated one in 10 reproductive-age women worldwide, and 50 to 70 per cent of women who experience painful periods, says Dr. Devon Evans, a Winnipeg-based OB/GYN who specializes in endometriosis and pelvic pain. He is an assistant professor and section head of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery in the department of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at the University of Manitoba and also started the Pelvic Pain and Endometriosis Clinic at St. Boniface Hospital. (“As of right now, it’s just me and the nursing staff and administrative support.”)

“If you have painful periods, you’re more likely to have endometriosis than to not have endometriosis.”

But despite how common endometriosis is, many women struggle to get a diagnosis or treatment. Their concerns are dismissed and they are gaslit about their pain.

“(Endometriosis) is, unfortunately, massively under-recognized and underappreciated worldwide, but has a major influence on people’s lives,” Evans says. “It can affect fertility, it can affect pain, it can affect actual organ function and overall quality of life.”

The road to getting an endometriosis diagnosis is neither clear nor short.

“There’s lots of literature out there, in Canada and elsewhere, that the average diagnostic delay from the onset of symptoms to a diagnosis — or even just seeing somebody who entertains the diagnosis — could be five to 10 years, or longer,” Evans says. The average, according to the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, is 5.4 years.

Historically, the only way to officially diagnose endometriosis has been through laparoscopy. Even though it’s minimally invasive surgery, it still requires a general anaesthetic, and there are long wait times to get in with a surgeon.

The quality of the surgery depends on the training of the surgeon, as well as the actual diagnostic accuracy of the surgery. “So one surgeon may look inside someone’s pelvis and say there’s no endometriosis, but maybe they didn’t know exactly what they’re looking for,” Evans says.

And the longer a diagnosis is delayed, the longer people suffer. Gobeil knows, because she’s lived it.

Her initial endometriosis diagnosis at age 28 was just the beginning of a saga that is still ongoing. Gobeil waited another year for an MRI. That scan revealed she had Stage 4, Grade 5 endometriosis, which is advanced.

“It was growing everywhere, and spreading throughout my pelvic region,” Gobeil says. “So, I had one ovary now that was encapsulated with endo, and very big. In fact, it was actually bigger than my actual uterus.”

High-stage endometriosis — determined by the severity and extent of adhesions, scarring and inflammation — can show up via non-invasive diagnostic tools, such as ultrasound, CT or MRI. But low-stage endometriosis is much more difficult to detect. The spots of tissue might be so small they aren’t picked up by an ultrasound, which is usually the first line of investigation for pelvic complaints.

That’s why it’s particularly difficult for patients to get an endometriosis diagnosis — and therefore earlier intervention — while they are still in their teens; by the time the disease has advanced to the point it’s visible on a scan, patients are well into adulthood.

Complicating things further, an ultrasound on a low-stage endometriosis patient may come back as “normal.”

“And one of the worst things that a doctor or a health-care practitioner can do is to relay that information back to somebody struggling with horribly painful periods, missing school, missing work, obviously having this affect their quality of life, and tell them that there’s nothing wrong,” Evans says.

As Gobeil encountered, those suffering with painful periods often have that pain invalidated and normalized. “A lot of women in their teens, even shortly after they get their period with debilitating pain and are missing school, are told that that’s normal and to suck it up,” Evans says.

And that dismissal can continue into adulthood. Cory Gregorashuk, 42, was missing at least one day of work a month because of her period when she was in her early 20s, and she didn’t have a regular GP.

“I found that any time I would bring it up places I would get sort of pushed along, pushed along, pushed along,” she says.

She says she also encountered biases from female doctors.

“I preferred male doctors. I found female doctors to be unsympathetic,” she says. “‘That’s normal.’ ‘That’s what we go through.’ ‘It’s just cramps.’ ‘It’s what women go through.’ Whereas male doctors would be like, ‘That sounds horrific — do you want a pain med?’”

Gregorashuk was in Grade 5 when she first got her period, and it was always heavy and painful. “I remember things like bleeding all over the bed at my babysitter’s house before school,” she recalls. She describes the pain as a “hot, dark, empty feeling.”

By her early 20s, Gregorashuk was frequently getting what she thought were urinary tract or bladder infections, accompanied by extreme pain, except her symptoms would resolve without antibiotics. Years later, she got a referral to a gynecologist who did a laparoscopy confirming she had Stage 2 (borderline Stage 3) endometriosis on one of her fallopian tubes.

Many patients get stuck in a years-long merry-go-round of referrals, misdiagnoses and waiting.

Alanna Martin, 33, had always had heavy, 10-day periods, but she developed worsening back pain and gastrointestinal issues in her early 20s. Martin works in the trades, and the pain was affecting her ability to do her job, especially after it began radiating down her left leg.

She tried chiropractic adjustments, yoga and massages, but nothing stopped the pain from returning.

At first she was told she had irritable bowel syndrome. Then anxiety. Then pelvic inflammatory disease. When she was 29, she got an ultrasound that revealed cysts on her ovaries.

Finally, at 32, Martin saw a specialist who diagnosed her with Stage 3 endometriosis, was open to discussing surgery for her cysts, and put her on Dienogest, a progestin medication. Martin finally felt like she was being heard.

But that doctor was a maternity-leave replacement; Martin’s followup was with the returning doctor, who was much less supportive. Martin was told she’d always have chronic pain, and was told to double up on her meds. “I left in tears,” she says.

Martin is currently on a waitlist for a new specialist. She says she feels trapped, in her body and the health-care system, which she doesn’t trust.

“At this point, if I get a really bad pain flareup, I just stay home,” she says. “I can’t call my doctor. I don’t go to the hospital. I obviously can’t call my specialist because it takes, like, three or four weeks to see them. I would rather just stay at home in bed for two or three days, sometimes a week, than even bother getting medical treatment.”

Endometriosis has no cure. It can be treated with medication, hormone therapy or surgery. Patients may undergo more conservative surgery to remove endometriosis lesions, adhesions and scar tissue, or they may opt for more aggressive approaches, such as removing the ovaries (oophorectomy) and/or the uterus (hysterectomy).

“The difficulty is, the ovaries are a double-edged sword,” Evans says. “While they are the origin of the hormones and the hormonal fluctuations that can cause and stimulate endometriosis-related inflammation and pain, they also are producing those same hormones that protect bone health, heart health, brain health.

“Removing ovaries prematurely — which we define as before the age of 45 or so — increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, heart attack, stroke, death, Alzheimer’s, osteoporosis and all kinds of things.”

People suffering with endometriosis are often forced to make a choice between longevity and quality of life as a young person, Evans says. “Which is not really a fair decision to have to make.”

The foundational treatment for endometriosis, Evans says, is hormonal therapy. “So suppression of those hormone fluctuations with things like birth control pills, or injections, or patches, or rings, or any type of hormone treatment that gets rid of those hormonal fluctuations that a woman’s body naturally produces,” he says.

But there are issues with hormonal treatments, too — intolerance, side-effects, cost.

“There can be other health implications of using some of those medications for a long time,” Evans says. “And then for people who are pursuing fertility, all of those options also prevent or impair fertility. So, a young person who’s looking to get pregnant, who has endometriosis or suspected endometriosis, can’t really access those mainstay medical treatments for endometriosis and so are left with surgery, pain medication and conservative means to manage their symptoms.

“It’s really tough.”

After Gregorashuk completed her fertility journey with the birth of her son seven years ago — its own separate story of health scares — she started using a hormonal intrauterine device, a contraceptive fitted inside the uterus, to manage her endometriosis symptoms. She still gets cramping, but it’s not as bad. Sometimes, she gets sharp, shooting pains in her rectum which she describes as debilitating. She’s gained weight and often has swollen feet or hands, but she doesn’t know if that’s from the IUD or the endometriosis.

“But I don’t really miss work anymore. I don’t have to use pads with tampons anymore. I don’t have the same cramping for days, that sort of stuff,” she says. “It’s a tradeoff.”

Of course, not every reproductive-age woman seeking endometriosis care wants to have children.

“Surgery that can improve your quality of life is halted because they think that you’re going to change your mind about having kids and it’s just like, where’s the quality of care in that?”– Alanna Martin

Martin says she was initially refused surgery for her ovarian cysts because it might affect her ability to get pregnant — something she doesn’t nor has ever wanted. “I even thought about getting my tubes tied as a teenager,” she says.

“Surgery that can improve your quality of life is halted because they think that you’re going to change your mind about having kids and it’s just like, where’s the quality of care in that?”

This is a frustration echoed by many other child-free women who have encountered similar barriers to pain-relieving surgery. It’s a remnant of paternalistic medicine, Evans says.

“I think most of the people who are looking for that kind of treatment, they’re mostly in their 20s or 30s or 40s — they’re adults. If they have been adequately informed of the pros and cons, the risks, benefits and alternatives to address their concerns and that’s still what they choose, then I don’t think that we should be obstructing their access to that service.”

Following her own Stage 4 endometriosis diagnosis, Gobeil opted for a hysterectomy at the age of 32. Surgeons removed the enlarged ovary, her cervix, her fallopian tubes, as well as her uterus. She kept her left ovary.

”I woke up in lots of pain after my hysterectomy, but also super-relieved and thrilled that my pain was actually going to be gone — that’s what I thought,” Gobeil says, the tears catching in her throat.

Surgeries such as hysterectomies can relieve endometriosis symptoms and pain, but they cannot cure the disease.

“A lot of people think that hysterectomy is a cure for endometriosis and it really, emphatically, is not,” Evans says. “Even after a hysterectomy, if somebody still has functioning ovaries, and they’re still in their reproductive years — or from their teens to their early 50s — they can still have endometriosis-related pain and symptoms. That’s something that needs to be really clear to people before they go ahead with an aggressive surgery.”

Gobeil had a stretch of good health in the years following her hysterectomy. She was able to play sports again. She took up running, and started training for half marathons.

“I loved my new body and I was pain-free,” she says. “I was fit, I was having fun, I was able to play with my young kids.”

But one day in 2018, Gobeil was out running with her neighbour when she began experiencing what felt like menstrual cramping. When she got home, she discovered she was bleeding from her vagina.

After a frustrating encounter with a GP who insisted her bleeding couldn’t be vaginal because Gobeil no longer has a cervix, Gobeil was finally referred back to her OB/GYN and, after a six-month wait, underwent a pelvic ultrasound which confirmed her fear: the endometriosis had come back.

“It was growing in my vagina, around my remaining ovary, and it attached itself to my ureter as well,” she says.

Gobeil began experimenting with medications to manage her endometriosis, including a year of Lupron injected via huge needle with horrible side-effects, including hot flashes, insomnia and pain so bad Gobeil couldn’t put on her own socks or walk up the stairs.

“Every cough or sneeze or sudden movement, everything, it felt like razors were cutting me from the inside. Living, smiling, showering, being intimate with my husband, all of it was impossible to do.”

Gobeil had her second surgery in 2022. Her remaining ovary was removed, along with more endometriosis tissue. But she began bleeding again in January of this year, and had a followup MRI in May.

The endometriosis is back. This time, it’s attached to her bowel, so she is waiting on seeing a colorectal surgeon — but that won’t happen until sometime in 2024. Her dosage of pain medication has increased. Her quality of life has decreased.

“What kind of life is this? I’ll tell you what this is like,” she wrote in a November update on Facebook. “It’s a living hell.”

Endometriosis is an invisible disease, which can also make it difficult for people to understand.

“I look fine from the outside, I look put-together,” Gobeil says. “But my family knows the real truth — I’m not. They see the struggles I do every day. And I hate that my family has this as their mother and wife. It’s very hard for me to understand and accept the fact that nobody signed up for this lemon mom.”

She laughs when she says this, but the pain can be heard in her voice.

Gobeil can’t exercise. She’s gained 40 pounds. Sometimes it takes three hours to get ready to go out. She has to “smile and lie” in public. She wants to show up for her kids. Her “mom-guilt” rages.

“I want to be there for their after-school sports. I want to show up at their concerts. I want to put a smile on my face and be happy, right? But I’m still fighting this life-taker, as I call it. Living with this never-ending chronic pain slowly drains the life right out of you.”

And so, Gobeil carefully rations her energy. She bought a few wigs so she doesn’t have to do her hair.

Martin, meanwhile, has hired a house cleaner and gets her groceries delivered. “I use all my energy to get through the work week and spend the weekends resting and sleeping,” she says.

Sometimes, Martin gets depressed when she thinks about the life she used to have. “I used to play drums in a band, go to concerts, travel,” she says. “Now I stay home and occupy my time with video games. I feel isolated and often lonely.”

Many people suffering with endometriosis have found lifelines online. Social media — and, in particular, Facebook groups dedicated to endometriosis — have been a source of support, validation and information.

Eileen Mary Holowka, 29, did a whole PhD dissertation about that very subject for Concordia University. Holowka, who is originally from Winnipeg and is now based in Montreal, began researching “Networks of Endometriosis: An Analysis of the Social Media Practices of People with Endometriosis” because they were interested in it, but also because they, too, suffered with endometriosis. (Holowka uses they/them pronouns and points out that non-binary folks don’t have great representation in conversations about endometriosis.)

“I always say you shouldn’t have to do your entire dissertation on endometriosis to feel like you have an understanding of it. Even after six years of a PhD, I still am learning things all the time.”

Holowka had never heard the word endometriosis until they Googled their own symptoms.

“That, to me, is a great example of how inaccessible information about endometriosis is, through the medical system, through sex education in school,” Holowka says. “I think these things are changing slowly. But for a lot of people, the internet, and specifically social media, is the best source of information sharing and knowledge sharing about endometriosis.”

It’s a complicated topic, as Holowka explores in their dissertation; social media is also a space in which people who are struggling with their health are preyed upon.

“There’s a lot of scams, there’s a lot of misinformation. There’s a lot of people trying to profit by selling essential oils to people who are sick. But endometriosis awareness has changed so much over the last 10 years, and I think a large part of that is because of advocates connecting on social media.”

Holowka notes that the ways in which social media is dismissed are not unlike the ways in which endometriosis is dismissed.

“It’s a really gendered form of dismissal. But people are practising advocacy, they’re practising community care, they’re practising information sharing. And it’s extremely powerful and meaningful to people as much as it’s also sometimes really toxic and problematic and chaotic, like social media always is. But it’s beautiful. And I think it’s really shaped the future for the disease.”

Gobeil belongs to a Winnipeg Facebook group called Endometriosis Warriors, and is also vocal on her personal accounts about her experiences.

“The stories we share, and the positivity we try to spread, and the knowledge we try to share is really heartwarming to see us all come together, where we’re each other’s support system,” she says.

“But we’re also there to advocate, too, for what we need to say to be seen or heard, because so many of the women in that group have not been seen or heard. And that, to me, is heartbreaking.”

Declining quality of life and frustration with waiting months (or years) for diagnosis and treatment has driven many Canadian patients to pursue treatment overseas, particularly in Romania. Per a Global News investigation, the Bucharest Endometriosis Center sees nearly 100 Canadian women every year.

Earlier this year, Melanie, a 39-year-old Manitoba woman, became one of them. She doesn’t want her last name used for fear of receiving stigmatized care here in Canada.

Melanie was often bedbound with pain that had intensified after the birth of her second child. She felt like she was missing her kids’ childhoods. Because she’d spent years taking birth control, being pregnant and breastfeeding, “it kind of silenced the symptoms, because knowing what I know now, I probably had this since my teen years, because I had the painful periods.”

She also had a feeling of pressure, like constipation. She was told to drink more water and eat more fibre, but the pain got worse. “It felt like there was a butcher knife in my rectum,” she says.

Melanie saw a gastroenterologist, got a colonoscopy and was diagnosed with IBS. She cut out dairy and gluten, but dietary changes didn’t ease her symptoms, and she began experiencing rectal bleeding tied to her menstrual cycle.

Melanie’s mom showed her an article she’d read about a Steinbach woman who’d gone to Romania for endometriosis surgery. “And I was like, this is crazy,” she recalls. “We live in Canada. Why would I go abroad for something like that?”

Then she met up with a friend of a friend who was also going to Romania for endometriosis surgery. Tired of waiting for a specialist here in Manitoba, Melanie rounded up all her medical records and contacted the surgeon in Romania. Within 24 hours, she heard back, and he was able to confirm she had endometriosis and adenomyosis, a condition that causes endometrial tissue in the lining of the uterus to grow into the muscular wall of the uterus.

“I never officially got diagnosed in Canada,” she says.

“I was so mad that this guy from halfway around the world was able to tell me what was wrong with me when I’ve been fighting for six years to get an answer.”– Melanie, a 39-year-old Manitoba woman who was diagnosed and treated for endometriosis at the Bucharest Endometriosis Center

Upon receiving a diagnosis, Melanie felt a mixture of relief and frustration.

“I was just mad that this guy … sorry,” she pauses, her voice breaking with emotion. “I was so mad that this guy from halfway around the world was able to tell me what was wrong with me when I’ve been fighting for six years to get an answer.”

She booked her March 2023 surgery in December 2022. “I could have gone as early as six to eight weeks after contacting him.”

In Romania, Melanie underwent a six-hour surgery during which her cervix, uterus and fallopian tubes were removed — along with about 12 centimetres of her sigmoid colon. “I did keep my ovaries,” she says.

The cost was just shy of $20,000, all in.

“I feel fantastic. No regrets,” she says. “I’m aware that there’s no true cure. There’s a chance that (the endometriosis) could come back. I hope that it doesn’t. But I feel really good with my decision that I think I saw one of the best, that I didn’t have to wait two or three years for anything to get dealt with. I was relieved to know that like it wasn’t in my head, that I wasn’t making up these stories, that it wasn’t that my pain tolerance was low.

“I don’t have pain. I haven’t taken any pain meds since before surgery. I haven’t taken the heat pack out.”

Evans, the OB/GYN, is aware of Canadian patients pursuing care overseas, and has concerns about continuity of care, as endometriosis is a chronic disease.

“People who are struggling with this need longitudinal care. It’s not a one-off thing. These centres outside of Canada that offer surgery for people looking for it — and will do it for you next week if you pay the bill — provide one-off care.”

He also has concerns about patients being properly informed about whether or not an expensive surgery is actually appropriate for them, as well as centres that claim they can cure endometriosis, “which is just a fallacy,” he says.

“Don’t get me wrong, I can see how people end up going that route, and I can see why. It’s important for people before they make that decision to go overseas for a surgery to make sure that the surgery they’re going for is really the surgery that they need. And they’re going there for timely access and not having inappropriate care because of what’s been advertised to them.”

More research. More funding. Better education. Better physician training. More timely access. Improved diagnostics.

These are among the things that would improve endometriosis care in Canada, according to the people treating and living with this disease.

Gregorashuk wants better access to gynecologists. “Why don’t little girls have gynecologists? Why are we seeing general practitioners most of the time? If you have a uterus you could be automatically connected with a gynecologist.”

Melanie agrees. She believes that with more research on endometriosis, she wouldn’t have to see multiple specialists for symptoms that were all related to endometriosis.

Martin knows the health-care system will not change overnight. “But there needs to be awareness for people to not only advocate if they haven’t got a diagnosis but to push to say, ‘Hey, maybe I do have this because symptoms are similar to what I have.’”

From a clinical perspective, Evans would like to see better awareness among primary-care providers and gynecologists. “That it’s not normal to be missing school, it’s not normal to be missing work. And that a negative ultrasound or a normal ultrasound does not rule out endometriosis. That’s a really important message.”

He says there’s increasing international consensus that endometriosis can and should be diagnosed without surgery, or as an option in addition to surgery. He points to the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, which put out a recommendation that endometriosis can be diagnosed through clinical and imaging characteristics consistent with the disease.

“That’s a huge step in the right direction to acknowledging people’s symptoms, and also helping them sort of put a name to their symptoms and start working on how they move forward in terms of the treatments,” he says.

Progress is happening, but it’s slow.

“There’s some work being done on non-invasive ways to diagnose even a low-stage endometriosis, like blood tests and special ultrasounds that can be done by people with extra training,” he says.

“But we’re years away from that becoming a standard sort of thing that a woman can access when she sees her doctor.”

jen.zoratti@winnipegfreepress.com

Jen Zoratti is a columnist and feature writer working in the Arts & Life department, as well as the author of the weekly newsletter NEXT. A National Newspaper Award finalist for arts and entertainment writing, Jen is a graduate of the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech and was a music writer before joining the Free Press in 2013. Read more about Jen.

Every piece of reporting Jen produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.