The trails less travelled

Walking historic Saskatchewan paths offers valuable insight into settler-Indigenous relations

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/05/2024 (620 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

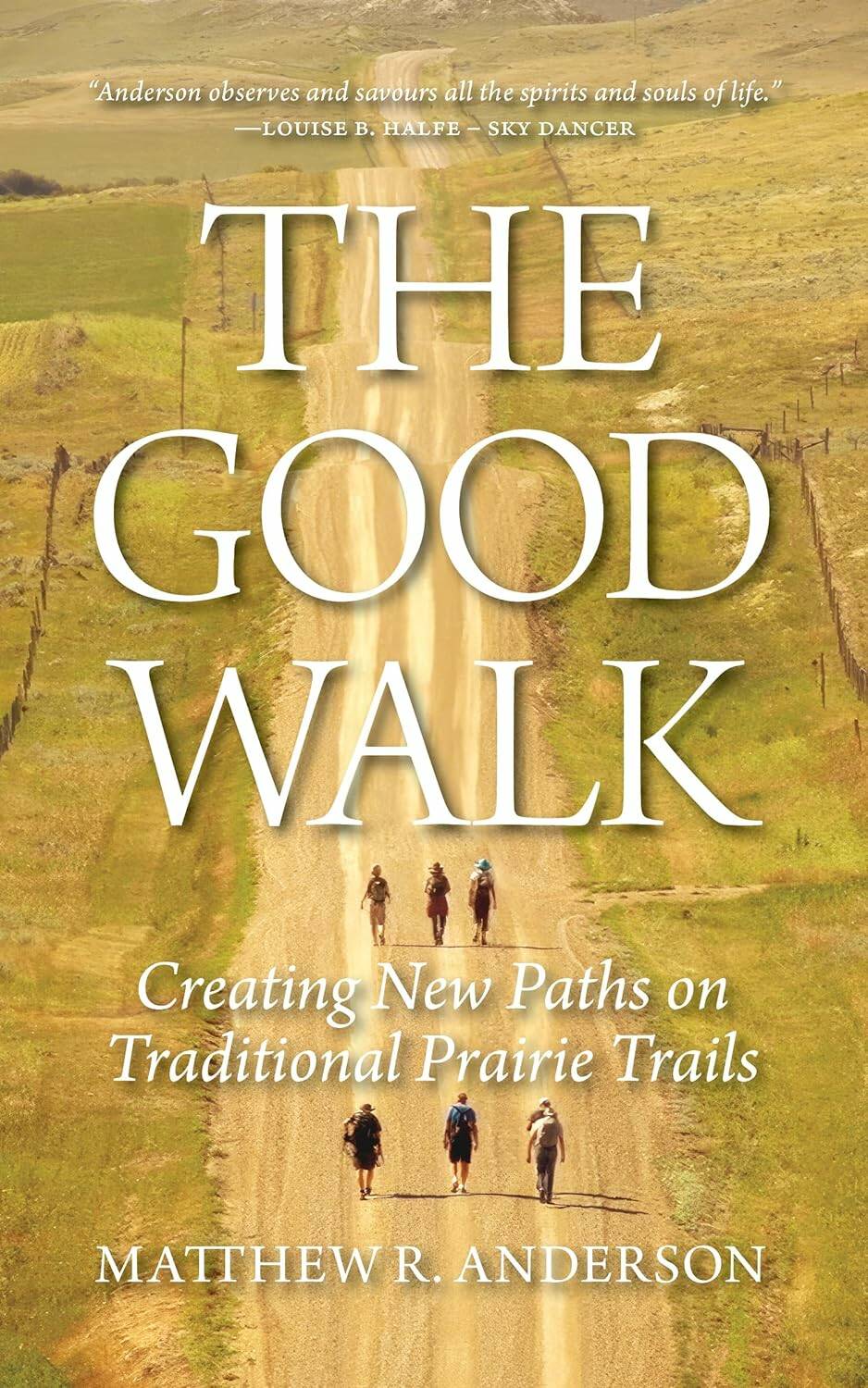

More than a fascinating account of trekking old, barely decipherable Saskatchewan trails, The Good Walk is a gift. It is an opportunity for looking deeper into Canadian history, an invitation to forge new relationships with the land and First Nations peoples.

This is author Matthew R. Anderson’s narrative of rediscovering and walking, with Indigenous, Métis and European-descended companions, two historic 350-kilometre routes — in 2015, the Traders’ Road (also called the North West Mounted Police Patrol Trail) and, in 2017, the Battleford Trail. Other annual Prairie walks organized since then are included in a single chapter but not developed in detail.

Born near the Cypress Hills, Anderson is a settler-descendent and a university lecturer (at St. Francis Xavier, Antigonish and Concordia University, Montreal) and scholar of pilgrimage and Canadian treaties (he co-wrote 2022’s Our Home and Treaty Land: Walking Our Creation Story with Raymond Aldred — revised in 2024). He is also a Lutheran pastor.

Blaise MacMullin photo

Matthew R. Anderson

These are good credentials. History is a continuum as much as any pathway. And here, the trails and relationships need work. Anderson’s writing is neither academic nor preachy. He sets a gentle pace and tone both in describing mindful prairie walks and dealing out hard facts. Footsteps with footnotes.

The walkers contend with prairie conditions (heat, dust, mud, ticks, no mobile phone service) and confront history (Where did people go? Why? What happened to them?). Along the way they receive food, refuge for camping and camaraderie from First Nations communities, Hutterite colonies, settler towns, ranchers, farmers and at such institutions as historic parks/sites and museums dotting the land. Anderson and other walkers offer presentations at these places, spotlighting the reasons for their journey — reviving and publicizing the local trail, encouraging interest in its maintenance, discussing the trail’s history and making new stories and connections in the process.

The Traders’ Road is a millennia-old east-west corridor along a continental divide from the Wood Mountain hills to the Cypress Hills, the highest elevation between Labrador and the Rockies (the walkers started at Wood Mountain Post and ended at Fort Walsh). The south-north Battleford Trail, from Swift Current to Fort Battleford, was established in settlement times by Métis freighters.

These trails have been the way to, and places of, mass bison slaughter, First Nations’ malnutrition, disease, starvation, forced relocation and, for the Métis too, abuse and attempted assimilation. By colonial thinking and policy, there had to be European agrarian settlement and, for that, the land had to be emptied.

The Traders’ Road and Battleford Trail pass through, respectively, Treaty 4 and Treaty 6 territories. Based on Indigenous culture, a holistic appreciation of the treaty negotiations and the context of those negotiations, probably most First Nations peoples and many other Canadians interpret these treaties as not relinquishing but sharing the land. It is a vision that has not been realized.

Anderson, who recognizes First Nations’ land sovereignty, points to European precedent for land sharing that respects people’s relationships to the land and each other. For example, in parts of England, Scotland and Wales, there are the Right of Reasonable Access laws, enabling public passage over historic trails on private land. In Finland and Norway, all have limited and responsible access over most private and rural land, what Anderson says are collective rather than individual rights “in a way much closer to the Indigenous conceptions of rights.” Pointing to a Canadian example of a better way of being, Anderson refers to “commons” lands, a historic concept where pasture is shared by different landowners. This approach, advantageous to the prairie ecosystem, is being used by some ranchers in southern Saskatchewan.

The Good Walk

At its heart, this is a current story. Breached promises, broken laws and inaction by successive federal governments have sown inequality for First Nations and Métis peoples and persistent mistrust between these communities and other Canadians.

A year before Anderson and his companions undertook the Battleford Trail, Colten Boushie, a Cree man, was shot and killed by Gerald Stanley, a white landowner, in contentious circumstances near Biggar, Sask. Stanley, who was charged with second-degree murder, had yet to stand trial and regional tensions were running high (Stanley would be acquitted by an apparently all-white jury; procedures for selecting juries were subsequently changed in Canada). For the walkers passing near the scene, this “dark pilgrimage” was a show of solidarity. Almost 40 per cent of the population of the North Battleford area is Indigenous. Anderson notes that many of the First Nations communities around Battleford are descended from Indigenous peoples expelled from the faraway Cypress Hills at the end of the 19th century.

This was a landscape of fences, “No Trespassing” signs and fear. Although mostly kindnesses were extended to the walkers on this journey, for the first time they encountered unfriendliness, including a man’s warning that they not stray onto his land (the walkers routinely pre-arranged permission to enter private property). Anderson regretfully maintains that their experience would have been less positive had their group not been primarily white.

Throughout Anderson’s narrative are accounts by observers from past times and writers of today. There are historic and contemporary photographs, as well as poems and whimsical sketches of the routes drawn by Anderson himself. These are fluidly interlaced with the immediate experience of fragrant sage and canola, spear grass that impales boots and feet, “calling” hawks, “zigzagging” antelope and rolling vistas where “the effect is like looking at the loose skin of a tawny-golden dog.”

At certain junctures in his account, Anderson hives off amply annotated sources “For Further Reading.” His interpretive comments provide a context for the reader who chooses to engage in these deviations en route.

For those who want to explore further, the reading lists are a compass homing in on specific topics in Canada’s multifaceted history. Collectively, they form a map to a mindset for thinking and possibly relating anew.

James R. Page photo

Anderson and a group of walkers follow a fence in a field west of the town of Val Marie, Sask.

Regardless of where one is on that journey, this book is an excellent (first) step.

Gail Perry is a long-distance walker who writes about history.

Matthew R. Anderson will be at McNally Robinson Booksellers’ Grant Park location to launch The Good Walk on Saturday, May 11 at 7 p.m.