A room with a view

July’s R-rated romp turns all-American road trip genre upside down

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/06/2024 (507 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

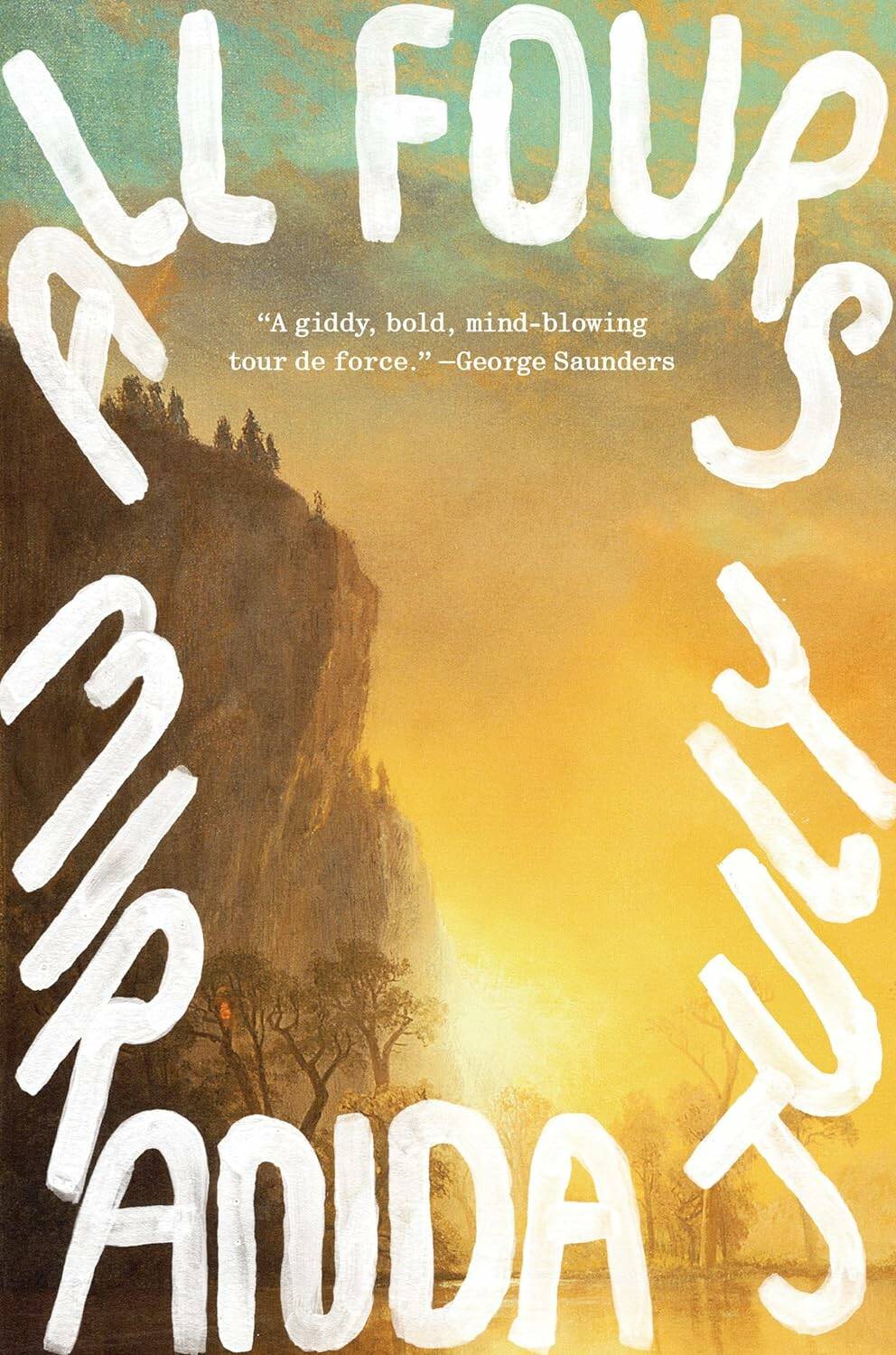

Frank, funny and horny, the latest work from multi-hyphenate Miranda July offers a disruptive and decidedly female take on the mid-life crisis novel. Creativity clashes with domesticity, pansexual desire crashes into perimenopause in this gloriously messy narrative, which is sometimes hilariously offhand, sometimes devastatingly sad but always knife-sharp.

July is a Los Angeles-based writer-artist-actor-filmmaker whose books include The First Bad Man and No One Belongs Here More Than You. All Fours’ unnamed first-person narrator seems to be a lot like July herself. “Picture a woman who had success in several mediums at a young age,” she says, calling up July’s niche kind of fame, along with a certain sense of careless privilege, which July deliberately plays up and then — at strategic points — satirically undercuts.

Our protagonist lives in a seemingly harmonious family arrangement with husband Harris, another impossibly cool member of the creative class, and their gender-non-binary eight-year-old kid, Sam.

Elizabeth Weinberg photo

Miranda July

As she turns 45, she finds herself imagining her life at a midway point, momentarily poised in the air before an inevitable downward trajectory. Having recently received $20,000 for a sentence she wrote that’s been used as a tagline in a foreign whisky ad — see what we mean about privilege? — she floats the idea of marking (or maybe mourning) this hinge-point birthday by driving cross-country to New York, staying at the very swanky Carlyle Hotel and then driving back.

After the issue of perimenopause is raised at a medical appointment, however, and after she finds a chart suggesting her libido is doomed to drop off a cliff at any moment, she ends up taking an odd detour.

At this point, July turns the all-American road trip genre upside down. Her character checks into a cheap motel less than a half-hour drive from her home and blows all the money — yes, all $20,000 — to upgrade her dingy little room. “Why do such a thing?” she asks herself. “What kind of monster makes a big show of going away and then hides out right nearby?”

Enclosed by a soft carpet of New Zealand wool, by curtains that seem to hold the glow of sunset at all hours of the day, by the irresistible smell of Tonka bean soap, the protagonist finds a heady freedom in the break from the routines of child care and householding. “The sudden absence of responsibility was a floaty, frothy, almost hallucinogenic weightlessness,” she suggests.

But what really blows up the narrator’s equilibrium, an equilibrium she has come to distrust, is her obsessive desire for Davey, a heedlessly beautiful twentysomething guy who works at the local Hertz rental counter.

All Fours can be read as an R-rated take on Virginia Woolf’s essay A Room of One’s Own. There are parallels to Rachel Cusk and her form-stretching experiments in literary autofiction. (Many readers will undoubtedly be Googling July’s bio, trying to figure out the fuzzed-up lines between fiction and fact.) And like Cusk, July plays deliberately and defiantly with the issue of “likability,” pointing up the fact it can be an issue for female writers in a way that it’s not for their male counterparts. (Likability is not something that, say, Philip Roth worried about in his late-life works.)

While the narrator spends much of her time in motel room 321, the writing ranges all over the place, purposefully. There are extended, unexpected and cliché-free erotic scenes, which lean into earthy details of urine and menstrual blood and benefit from July’s sense that “ecstasy has a kind of built-in ridiculousness.”

All Fours

There are disquisitions on art and celebrity and hormone levels that feel like tight-10 comedy bits. There are deeply emotional passages when the narrator flashes back to her harrowing experience of childbirth, which involved a fetal-maternal hemorrhage, and then weeks when infant Sam was balanced precariously between life and death in the neonatal ICU.

Some sequences, dizzily engaged with the possibilities of language and narrative, feel surreal. A final section, in which the narrator crowd-sources reactions to aging, identity and relationships from a group of friends, even feels a little programmatic, like a filthy but helpful magazine article.

What keeps everything together is July’s original, idiosyncratic and unafraid voice.

Alison Gillmor writes on pop culture for the Free Press.

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.