Clearing their names Indigenous people are more likely to be wrongfully convicted but less likely to be exonerated; new law aims to tackle inequities

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/01/2025 (356 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The news shook the small community of Pinaymootang First Nation: four of their young men convicted of killing a stranger in Winnipeg.

Garnet Woodhouse grew up with all four on the Interlake reserve, then known as Fairford.

He knew them as quiet, hard-working and kind, and he believed them when they said they were innocent.

“Other families out there, I’m sure they’re feeling the same way — ‘How do we get a lawyer and how do we start pushing this forward in the legal system?’”–Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak

But what could be done? It was 1974 and they were Anishinaabe, ages 17 to 21, who didn’t speak fluent English. It would be their word against that of big city police and prosecutors.

“It was a disaster,” Woodhouse says today of what they went through. “Those guys would never hurt a fly.”

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS Garnet Woodhouse grew up on Pinaymootang First Nation with the four young Indigenous men wrongfully convicted in 1974. The community always believed they were innocent, he said.

The four men are Brian Anderson, Allan Woodhouse, Clarence Woodhouse and Russell Woodhouse. Collectively, they spent more than five decades in prison and then dozens more years on parole. It took 50 years for a judge to finally declare the first three innocent — Brian and Allan in 2023, Clarence last summer. Russell’s case is still ongoing, posthumously. He died in 2011.

Advocates for the wrongfully convicted are pleased to see the cases finally being resolved, but emphasize the men’s ordeal highlights the additional obstacles Indigenous people — who are overrepresented in Manitoba’s justice system — face when it comes to fighting injustice.

Systemic racism, they say, continues to contribute to miscarriages of justice.

And while several initiatives are being proposed that could address those issues — including an independent review commission at the federal level and a provincial-federal task force looking at potential wrongful convictions of Indigenous people in Manitoba — experts say more needs to be done.

Indigenous people are more likely to experience miscarriages of justice, yet that fact is not reflected in exoneration statistics, experts say.

“The criminal legal system has a disproportionate impact on the lives of Indigenous people in Canada,” said Emma Cunliffe, a law professor at the University of British Columbia’s Allard School of Law. “They’re disproportionately likely to be criminalized and incarcerated for offences and behaviours that, for a differently situated accused person, would not result in criminalization or incarceration.

“That essentially creates a greater pool from which wrongful convictions can arise.”

Indigenous people account for 32 per cent of all prisoners in the federal correctional system, despite making up five per cent of Canada’s population and about 18 per cent of Manitoba’s population. Half of all federally incarcerated women are Indigenous, according to 2023 data from Public Safety Canada.

In Manitoba’s jails, those rates are higher. Here, 85 per cent of female and 77 per cent of male offenders identify as Indigenous, according to data provided by the province. For youth in correctional facilities, those rates are 83 and 87 per cent for girls and boys, respectively.

Despite these rates of incarceration, Indigenous people across Canada are less likely to be granted a legal remedy in a wrongful conviction case.

Of the 30 remedies — meaning a new trial or appeal — ordered by the federal justice minister since 2003, five involved Indigenous people, including Brian Anderson, Allan Woodhouse and Clarence Woodhouse, according to data provided by the federal Department of Justice.

One remedy was for a Black Canadian. None were for women.

Systemic racism plays an undeniable role in these statistics, experts say, but so do other pitfalls of the justice system.

For instance, in the current system, after exhausting all appeals, there is one last avenue of recourse — an application for a ministerial review by the federal justice minister. The application must include new and significant information that could lead the justice minister to determine the person has “likely” suffered a miscarriage of justice. This can include scientific evidence such as DNA that proves the person wasn’t responsible, information that confirms an alibi, proof that valuable evidence was not disclosed at trial or that a witness gave false testimony.

This in-depth re-investigation work typically requires a lawyer’s assistance — which means either having the resources to pay for one or relying on innocence advocates to take up the file.

Innocence advocacy groups, such as the esteemed not-for-profit Innocence Canada, or smaller endeavours operated through universities, tend to focus on cases where “factual innocence” can be proven — showing that the person convicted did not commit the crime. They also tend to focus on more serious crimes, such as murder, where sentences are typically longer. This is largely due to limited resources and the time and work it takes to prepare an application. The result is that anyone falling below the bar of factual innocence regarding serious crimes are unlikely to get the necessary expert eyes on their case before bringing it to the federal justice minister for review.

Innocence checklist

Wrongful convictions, or at least “unsafe verdicts” — that is, those that can lead to a wrongful conviction or a miscarriage of justice — may emerge from cases that include one or more of the following:

Prosecutors withholding disclosure: This occurs when the Crown has withheld evidence, either intentionally or unintentionally, that could impact the outcome of a trial. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled in a landmark case from 1991, R v. Stinchcombe, that the Crown must disclose all evidence to the defence.

Wrongful convictions, or at least “unsafe verdicts” — that is, those that can lead to a wrongful conviction or a miscarriage of justice — may emerge from cases that include one or more of the following:

Prosecutors withholding disclosure: This occurs when the Crown has withheld evidence, either intentionally or unintentionally, that could impact the outcome of a trial. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled in a landmark case from 1991, R v. Stinchcombe, that the Crown must disclose all evidence to the defence.

Hiding witnesses: Preventing potential witnesses for the defence from testifying.

Police misconduct or corruption: This includes false testimony, coerced confessions, poor or missing record keeping, withholding evidence from the Crown or a pattern of past misconduct.

Alternate suspect: The presence of evidence suggesting someone else committed the crime, confessions of incriminating evidence involving someone else, or a witness identifying someone else as the culprit.

New or changing science: When science has evolved to the point that evidence presented at trial could be tested or re-tested and exculpate the person convicted.

Diminished mental capacity: If the defendent has a serious mental illness or intellectual disability. Contributing factors here could include someone’s youth, unsophistication or lack of education.

Witness incentives or jailhouse informants: This can include deals or incentives such as perks or benefits offered in exchange for testifying. This can also include threats if they don’t testify.

Maintaining innocence: If the defendant insists they are innocent.

Unreliable eyewitness identification: Especially relevant in cases where someone has identified a stranger through a process that suggested they were correct, when that may not actually be the case. Also included is if there is a lack of other evidence corroborating the eyewitness identification.

Pretrial publicity: Cases involving intense media scrutiny prior to trial that puts pressure on actors in the justice system to conclude a matter. This can include cases where public figures, including police, have commented publicly on the defendant’s — or witness’s — character, past or reputation.

Racism: This can include racism on the part of police, the Crown, judges, etc.

Tunnel vision: When police or prosecutors zero in on one suspect or theory to the detriment of the investigation and justice, including possibly disregarding alternate suspects or theories.

Noble cause corruption: When police or Crowns feel justified in taking illegal or unethical action to secure a desired outcome, such as in cases where it’s suspected the defendant may be a bad actor of sorts and belongs in jail even if they didn’t commit the crime they’ve been charged with.

Types of wrongful convictions

There remains a lack of consensus on what should be characterized as a “wrongful conviction” — which can involve proving factual innocence — or “miscarriage of justice,” where the justice system failed. Some legal experts argue that in cases where people plead guilty to more serious offences than they could have been charged with, receive too harsh sentences, or aren’t provided with a proper defence, this should be considered a miscarriage of justice.

The following are examples of wrongful convictions:

False guilty pleas: When someone pleads guilty to a crime they did not commit for a range of reasons. This can include accepting a plea deal to avoid trial or having already served enough time on remand to be freed after entering a plea.

Wrong perpetrator: The wrong person was convicted. Someone else committed the crime.

No crime: The crime is imagined, in the sense that no crime occured but police and the Crown believe an offence was committed. An example is when a child dies by natural causes but the justice system determines criminal intent was involved.

— Information drawn from interviews with legal experts, as well as Kent Roach’s book, Wrongfully Convicted: Guilty Pleas, Imagined Crimes and What Canada Must Do To Safeguard Justice, and Carrie Leonetti’s academic article, “The Innocence checklist.”

The Criminal Conviction Review Group, a body of lawyers that assesses the files, has only received about 220 applications since 2003. The group does not track official demographic data on who is submitting applications.

But change could be coming.

Bill C-40, the Miscarriage of Justice Review Commission Act — also known as David and Joyce Milgaard’s Law — introduced by former federal justice minister David Lametti in 2023, proposes to broaden the review process by making the decision body independent of the political system and conducting outreach with marginalized groups. The bill, which received royal assent in December, would also lower the standard for wrongful conviction decisions — switching from cases where there is a reasonable basis to believe a miscarriage of justice “likely” occurred to those where it “may” have occurred. The hope is that this change will encompass more cases.

In New Zealand, a similar independent review commission established in 2019 is seeing higher rates of applicants from Maori and Pacific peoples. Prior to the new commission, even though Indigenous people make up more than 60 per cent of the prison population in New Zealand, less than 16 per cent of applications for remedies came from Indigenous people. Now those rates are closer to 50 per cent, according to the country’s Criminal Cases Review Commission data.

Canadian Senator Kim Pate points to statistics showing how few Indigenous people in the justice system are being offered legal remedies.

She fears the progressive changes proposed in Bill C-40 will be stunted by a lack of resources.

“If there is underfunding, the chances of the Indigenous women being prioritized are not great,” Pate said. “If you’ve got limited funds, the chances are that those kinds of biases will continue to be exercised.”

Sen. Kim Pate fears the proposed independent review commission will be stunted by inadequate resources.

Pate, who co-authored a 2022 report calling for the cases of 12 Indigenous women, including two in Manitoba, to be reviewed as potential miscarriages of justice, worries Indigenous women will continue to be underserved by the proposed commission.

One of her key concerns is that there will be no allowance for the review of sentences.

“It may be that the person was somehow criminally responsible for some part of what happened, but it should have been a different conviction,” Pate said. “The way to remedy it may be a different conviction and a shorter sentence, or to shorten the sentence if the context was not taken into account.”

She offered the example of Helen Naslund, a woman in rural Alberta who was sentenced to 18 years in prison in 2020 after pleading guilty to killing her abusive husband in 2011. After public outcry and an appeal in 2022, Naslund’s sentence was reduced to nine years minus time served. The Appeal Court took into account “battered woman syndrome,” a psychological condition stemming from continuous abuse by an intimate partner.

And while proponents of Bill C-40 say the new commission will use outreach to encourage disadvantaged individuals to apply, some remain skeptical.

Canadian Registry of Wrongful Convictions co-founder Amanda Carling says building trust with marginalized communities is critical for the commission.

“If you’ve got limited funds, the chances are that those kinds of biases will continue to be exercised.”–Sen. Kim Pate

Amanda Carling, a lawyer and co-founder of the Canadian Registry of Wrongful Convictions, which tracks historical cases across the country, said any outreach initiatives need to be carefully thought out.

“The way that the new commission goes about doing outreach is going to be really important,” said Carling, who is Métis and grew up in Winnipeg. “Making sure that the staff are from community and seem approachable (is necessary) … When non-Indigenous organizations are doing this work, from the perspective of community members, they’re just part of the same system that oppresses.”

Experts have also voiced concerns over the lack of guaranteed Indigenous representation in the commissioners’ role, something New Zealand has mandated.

“I think Indigenous people have every reason to lose confidence in the justice system and … we need to show that there actually is a place that they can go to have injustices rectified,” said Kent Roach, a professor of law at the University of Toronto who also co-founded the Canadian Registry of Wrongful Convictions and was part of consultations on Bill C-40.

MARTA IWANEK / FOR THE FREE PRESS

Roach said he hopes the proposed commission in Canada will be sufficiently independent from politics and somewhat removed from the current colonial system so it cultivates trust within communities. He agrees with Carling that this requires meaningful outreach.

There’s no question racism was a factor in the convictions of Brian Anderson, Allan Woodhouse, Clarence Woodhouse and Russell Woodhouse.

“Systemic racism impacted the investigation, the prosecution and the adjudication of this case,” Crown prosecutor Michele Jules said at the July 2023 hearing for Brian Anderson and Allan Woodhouse.

She called no evidence, saying the case “fell well below” the standards for prosecution in 1974, and “wouldn’t even come close” to meeting today’s standards.

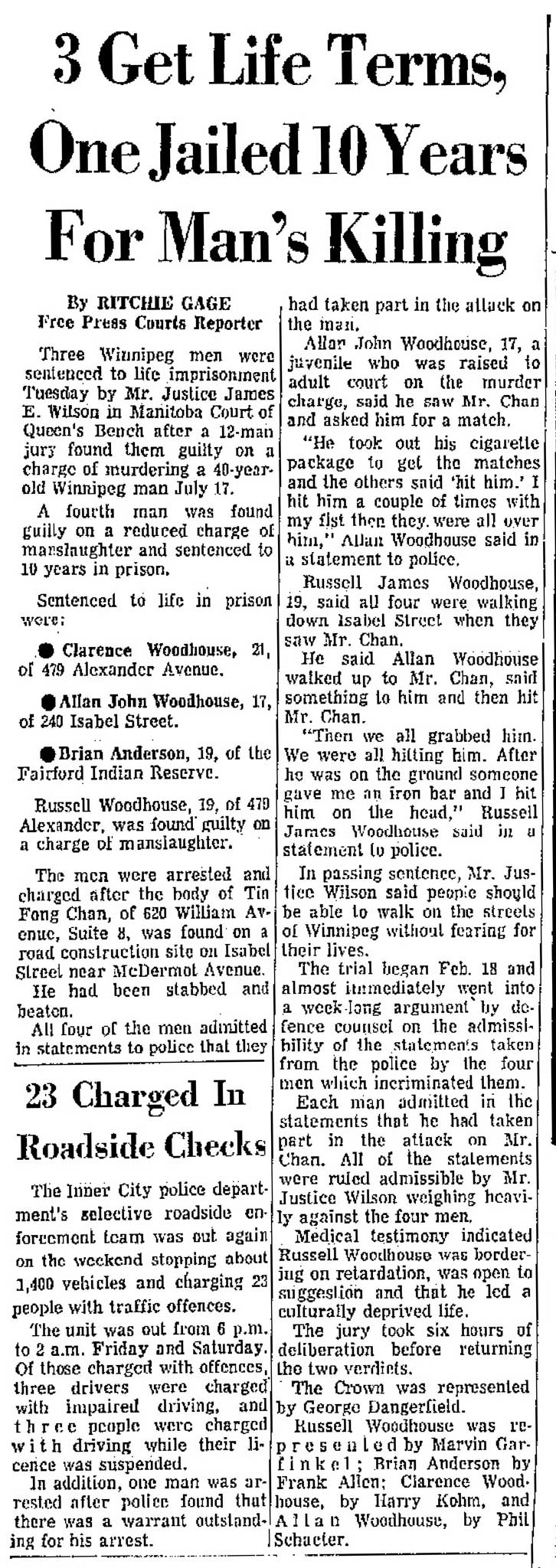

A clipping from the Winnipeg Free Press on March 6, 1974 about the sentencing of Clarence Woodhouse, John Woodhouse, Brian Anderson and Russell Woodhouse.Court heard the men were beaten by police and forced to sign false confessions written in English, despite none of them being fluent in the language. Clarence Woodhouse required the assistance of a Saulteaux interpreter to testify.

All four told the court they were not involved in the murder of Ting Fong Chan, a restaurant worker and father of two. They said their confessions had been extorted. Brian Anderson said police slapped and punched him.

The judge refused to believe him.

“The story is incredible unless one accepts the fact that these things do go on in police headquarters at the Public Safety Building but there is no evidence of that beyond what this young man says,” said Justice James E. Wilson in his ruling. “I reject as a complete fabrication this evidence that police officers, certainly in the circumstances which were detailed to me here, would lay themselves open to the difficulties which they could face if statements were obtained in this fashion.”

At Russell Woodhouse’s sentencing, Wilson used overtly racist language.

“This is not a jungle where we live. It is not a wild land. We are not subduing this land from anybody, we are not still taking it from wild people,” he said.

Brian Anderson, Allan Woodhouse and Clarence Woodhouse were all convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Russell Woodhouse was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

George Dangerfield, a former Manitoba Crown who was later linked to four other wrongful convictions, was the prosecutor. He praised the police for their hard work in a 1976 letter addressed to the chief constable of Winnipeg police.

“May I take this opportunity to say once again how tremendously impressed I was with the work of the members of your police force connected with this case,” Dangerfield wrote, as detailed in submissions prepared by Innocence Canada.

He singled out the officers accused of beating the men and forcing them to sign confessions, saying that without the confessions “this case would have been lost entirely.”

The comments from Dangerfield and Wilson were in stark contrast to how Manitoba Court of King’s Bench Chief Justice Glenn Joyal responded in 2023.

“You are innocent,” he told Brian Anderson and Allan Woodhouse, echoing the same comments when Clarence Woodhouse’s case came before him a year later. Joyal apologized to the men and said the entire case against them was rooted in systemic racism.

“You are heroes in every sense of the word,” he said.

In 2023, Court of King's Bench Justice Glenn Joyal formally apologized to Brian Anderson, Allan Woodhouse, Clarence Woodhouse and Russell Woodhouse for the court's systemic racism that led to their wrongful convictions.In an October interview with the Free Press, Joyal said systemic discrimination in the judicial system must be called out and addressed.

“Our systems aren’t perfect, our institutions aren’t perfect,” Joyal said. “We are going to fail sometimes. Every example of a miscarriage of justice is an example of a systemic failure.”

Asked why he chose to go so far as to declare the men “innocent” — something judges rarely, if ever, do — Joyal said he felt obligated to do so in light of the miscarriage of justice they suffered.

“We have to make these people whole,” Joyal said.

In the wake of this case, Indigenous leaders have called for broader judicial reform.

“I can’t sit here as National Chief and be confident that there’s still not wrongful convictions happening,” said Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, in an interview with the Free Press. “How do we safeguard ourselves against that?”

Woodhouse Nepinak is hopeful Bill C-40 will address systemic racism in issues of injustice, something critics are skeptical it will have the capacity to accomplish. She would also like to see a cross-Canada commission focused on potential wrongful conviction cases involving Indigenous people.

“Let’s set up an entity and go across the country, figure out where the gaps are and where they were,” she said.

Cathy Merrick, the late Grand Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs who died in September, described the acquittals as potential “catalysts of change.”

“The criminal justice system has failed Indigenous people… It is clear that there are other cases out there. The court can’t solve these issues by itself.”–Lawyer Jerome Kennedy

“This is a sign that we can confront the systemic injustice that plagues our society,” she said at a press conference the day after Brian Anderson and Allan Woodhouse were declared innocent.

“It’s not OK. It’s not a mere blip or a mistake. It’s a pattern of injustice and discrimination that must be addressed.”

Woodhouse Nepinak would also like to see an independent body probe the actions of the police officers at the centre of the case involving Anderson and the Woodhouses. She wonders how many other cases those officers might have influenced.

In its submissions, Innocence Canada points to other cases of probable false confessions where the same officers were involved. In one, a 1977 rape and murder case, the same detectives obtained purported voluntary confessions from three Indigenous men. Their lawyers later proved their clients had alibis and claimed they did not confess, and the charges were stayed.

“Coming only a few years after the arrest of Mr. Anderson and Mr. Woodhouse, this case adds considerable weight to their claims of how they were treated by members of the same police squad,” Innocence Canada wrote.

Asked if police have launched any internal probes into the actions of the officers involved in the 1974 case, Winnipeg police would only say they consider the investigation into the murder of Ting Fong Chan to be “open.”

“As such we are unable to comment on the status or developments in the investigation.”

Innocence Canada has also been calling for change that targets systemic racism in the justice system.

During the hearing for Clarence Woodhouse in October, Innocence Canada lawyer Jerome Kennedy proposed a provincial-federal task force that would work with Indigenous leaders to identify potential wrongful conviction cases involving Indigenous people. The lawyers’ submissions also noted certain individuals, including these young Anishinaabe men who didn’t speak fluent English, may be especially vulnerable to false confessions and be “prone to accept and believe police suggestions made during the course of the interrogation.”

“The criminal justice system has failed Indigenous people,” Kennedy said in court. “It is clear that there are other cases out there. The court can’t solve these issues by itself.”

These calls are not new. The 1991 Aboriginal Justice Inquiry of Manitoba revealed damning evidence of systemic racism within Manitoba’s criminal justice system and within the Winnipeg police department.

The inquiry, co-led by the late Murray Sinclair, a provincial court judge at the time, was called in response to the killings of two Indigenous people in Manitoba — Helen Betty Osborne in 1971 and the Winnipeg police killing of Island Lake Tribal Council executive director J.J. Harper in 1988. The final report made 296 recommendations to address discrimination against Indigenous people in the justice system.

“A lot of that work is still sitting on the shelves collecting dust,” said Woodhouse Nepinak. “Some work has been done on some of these reports, but we have a long way to go.”

As recently as 2017, a Manitoba case highlights the ease with which a miscarriage of justice can occur.

That year, 32-year-old Richard Joseph Catcheway pleaded guilty to charges of breaking into and entering a Winnipeg home.

But Catcheway, who grew up in the Manitoba foster-care system and suffered from fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and addictions, couldn’t possibly have done the crime. At the time of the break-in, he was 200 kilometres away, serving time for another crime at the Brandon Correctional Centre.

Still, he served six months in jail for the break-in before anyone realized he was innocent.

In 2018, the Manitoba Court of Appeal quashed his conviction. The case raised questions about whether Indigenous people sometimes plead guilty due to lack of resources, language supports or understanding to advocate for their innocence.

For Woodhouse Nepinak, these matters are personal.

“In my own family, this has happened,” she said of wrongful convictions.

Russell Woodhouse, a relative, was like a second father to her, she says.

After his release from prison, Russell Woodhouse helped raise her on Pinaymootang First Nation. After being subjected to a wrongful conviction and systemic racism in Winnipeg, he preferred to be home in the community around people he could trust, Woodhouse Nepinak said.

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS National Chief Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak, with her dad Garnet Woodhouse, says more safeguards are required to prevent wrongful convictions.

She’d always wanted to help him clear his name, but without money for lawyers, the family was at a loss.

“It was complicated,” she said. “Other families out there, I’m sure they’re feeling the same way — ‘How do we get a lawyer and how do we start pushing this forward in the legal system?’”

She is hopeful Bill C-40 will make the application process less daunting for those who don’t have the resources or legal know-how to support their loved ones.

She says it’s “appalling” it’s taken so long for Russell Woodhouse and the other men — including Russell’s brother, Clarence — to be exonerated, but she is grateful for the work of Innocence Canada. The not-for-profit filed an application for a posthumous ministerial review of Russell’s case last year. The file remains with the federal justice minister.

As for Garnet Woodhouse, he hopes Russell will one day get the justice he was denied while he was alive.

He says when he’d ask Russell just what had happened in Winnipeg all those years ago, he always gave the same answer.

“We never did anything wrong.”

katrina.clarke@freepress.mb.ca

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Righting the wrongs

A Free Press examination of miscarriages of justice and the legacy of legendary prosecutor George Dangerfield

Born and raised in and around Toronto, Dan Lett came to Winnipeg in 1986, less than a year out of journalism school with a lifelong dream to be a newspaper reporter.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.