The long, hard road to exoneration Robert Sanderson holds onto hope for a new trial — rather than just a stay of proceedings — so he can be fully acquitted of the 1996 triple murder for which he served 25 years in prison

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/11/2023 (860 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

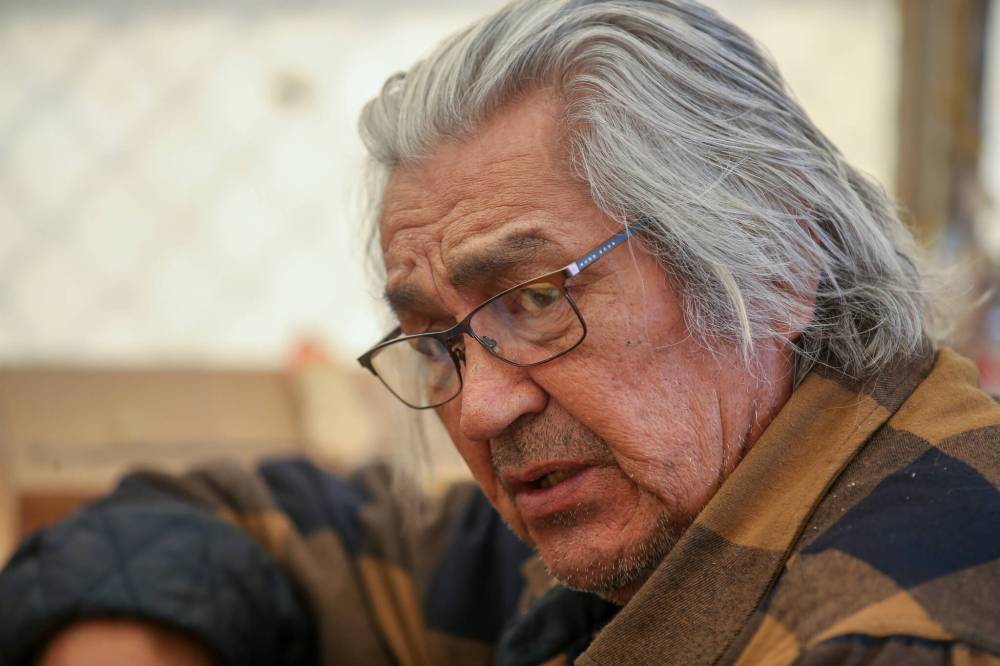

VANCOUVER ISLAND — Robert Sanderson leans his large frame back in a small chair and lights up the first of many cigarettes to come.

This is where he feels most at home: in a large white tent in a nondescript gravel lot on Vancouver Island filled with in-the-works totem poles and a supply of wood. He calls it the “carving shack.”

It’s owned by his good friend and mentor, Tom LaFortune, who is helping Sanderson cement himself as a talented Métis and Ojibwe multi-disciplinary artist and to create a new life for himself in British Columbia.

Sanderson is still adjusting to freedom. He spent 25 years in prison for three murders he says he did not commit.

When the Free Press visited him earlier this year, he’d been out on parole for two years. He’s still amazed by technology like smartphones and self-driving cars, to say nothing of the small joy of walking into a grocery store and buying whatever he wants.

His conditions of release, however, mean he is obligated to inform his parole officer of his movements and meetings, including this interview with a reporter.

He is free, conditionally.

In 1996, Sanderson was arrested and charged in connection to the grisly slayings of three men in what police said was a gang turf war over control of Winnipeg’s sex trade. He pleaded not guilty but in 1997 was convicted of three counts of first-degree murder, along with two other men, and sentenced to life in prison.

Sanderson acknowledges he wasn’t a saint in his former life — the court was told about possible gang affiliation, involvement in prostitution rings and links to the drug trade — but he insists he’s not a murderer.

Soon, the law may agree with him.

In February, former federal justice minister David Lametti made the rare decision to refer Sanderson’s case back to the Manitoba Court of Appeal. This could ultimately lead to his exoneration, freeing him from restrictive parole conditions he will otherwise be bound to for the rest of his life.

“After a thorough review of Mr. Sanderson’s case, I am satisfied that there is a reasonable basis to conclude that a miscarriage of justice likely occurred and that a new appeal from conviction is warranted,” Lametti said in a release at the time.

But the wheels of justice move slowly. Eight months later, Sanderson’s case remains in limbo.

As complicated and drawn-out as this process has been, Sanderson knows he’s a small part of a tangled and growing web of injustice and suspected and confirmed wrongful convictions in Manitoba.

At its centre is one man. Former star Manitoba Crown attorney George Dangerfield today holds Canada’s record for the most wrongful convictions: five cases and six men who collectively spent dozens of years in prison for crimes they did not commit.

Decades after Dangerfield prosecuted these cases, his victims are still fighting for justice.

One 50-year-old case, the fifth confirmed to be a wrongful conviction involving Dangerfield, recently made national headlines.

In 1974, Brian Anderson, Allan (A.J.) Woodhouse and Clarence Woodhouse were convicted of murdering restaurant worker and father Ting Fong Chan as he walked home following his shift. A fourth man, Russell Woodhouse, Clarence’s brother, was convicted of manslaughter. The men, then in their late teens and early 20s, were from Pinaymootang First Nation, located 230 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg.

They said Winnipeg police beat them and forced them to sign false confessions in English, a language none was fluent in. They always maintained their innocence.

In July, two of the four, Brian Anderson and A.J. Woodhouse, became free men. One month earlier, Lametti had ordered a new trial for the duo after Innocence Canada, a national group advocating on behalf of the wrongfully convicted, filed an application for a federal review on their behalf.

At the July trial, a judge fully exonerated them, calling them “innocent” of the crime and apologizing for the justice system’s failure.

Innocence Canada has now filed review applications for both Clarence Woodhouse, who was released from custody last week after his parole was suspended, and Russell Woodhouse, who died in 2011. The outcomes of these applications are pending.

The other high-profile Dangerfield cases that resulted in miscarriages of justice include: James Driskell, Thomas Sophonow, Kyle Unger and Frank Ostrowski, all men wrongfully convicted of murder and robbed of years of their lives.

And as a result, the murders of Perry Harder (1990), 16-year-old Barbara Stoppel (1981), 16-year-old Brigitte Grenier (1990), Robert Nieman (1986) and, now, Ting Fong Chan (1973), all remain unsolved.

As for Sanderson in B.C., he too is hoping he may soon join the growing ranks of Manitoba’s wrongfully convicted.

At the carving shack, Sanderson greets a reporter and photographer on a sunny, windy weekday wearing a grey checkered jacket, a grey shirt and a backwards ball-cap, his long salt-and-pepper hair tied back. He has a deep, commanding voice but a calm manner and easygoing way of speaking.

He settles into a cushioned office chair, surrounded by woodworking projects.

He starts talking about his art — jewelry, digital creations and intricate wood carvings. Art is where his passion lies these days. It’s also where his lawyers would prefer any conversations with reporters stay, conscious of the case not yet being fully resolved.

But his mind is also on his past. And his future.

“Do I put my faith in the Manitoba system? Because (my faith) has been totally shattered.”

“Now comes the hard part — do I put my faith in the Manitoba system?” he says. “Because (my faith) has been totally shattered.”

Sanderson is accustomed to disappointment and not being believed.

In 1996, Sanderson became the police’s focus in a murder investigation partly because they found blood from three men killed at a West Kildonan home in his car, along with a bloody baseball bat. Sanderson told police he loaned out his car but he refused to “rat out” the person to whom he had lent it.

“I’m not saying my car wasn’t there,” he told police the day after the killings. “I wasn’t there.”

But police also found a hair on a foot of a victim at the crime scene. At trial, an expert Crown witness said the hair belonged to Sanderson, based on microscopic analysis.

Adding to that, two witnesses testified against Sanderson and the two other accused, Roger Sanderson (no relation) and Robert Tews.

A 15-year-old, who said she was a former sex worker who worked for Robert Sanderson, testified she saw him leave their hotel room with guns and knives the night of the murder and return with bloody clothes and jewelry.

Brent Stevenson, 20, who was a friend of the 15-year-old and a former gang associate, testified that Roger Sanderson confessed to him that Robert Sanderson and Tews were his co-conspirators in the murders.

A jury convicted all three men, sentencing them to life in prison.

But here’s what the jury didn’t know:

- the Winnipeg Police Service would pay Stevenson $15,000 and relocate him outside of Manitoba after the trial;

- all but one of six criminal charges Stevenson was facing were stayed;

- the 15-year-old former sex worker went on to date Stevenson; and

- in 2004, advanced technology would prove the hair didn’t belong to Sanderson.

These elements would later be known as Dangerfield trademarks:

- withholding information from the defence;

- reliance on dubious evidence;

- making deals with jailhouse informants in exchange for testimony; and

- failing to disclose deals to jurors.

But Sanderson remained in prison. The Manitoba Court of Appeal dismissed his appeal in March 1999 and he was refused leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada that year.

Despite an application for ministerial review in 2017, he was denied bail in 2018.

Timeline

Aug. 6, 1996: Thomas Krowetz, 27, Stefan Zurstegge, 24, and Jason Gross, 22, are found tortured, shot and stabbed inside 319 Semple Ave.

Sept. 20, 1996: Robert Sanderson is charged with three counts of first-degree murder, alongside Roger Sanderson (no relation) and Robert Tews.

Aug. 6, 1996: Thomas Krowetz, 27, Stefan Zurstegge, 24, and Jason Gross, 22, are found tortured, shot and stabbed inside 319 Semple Ave.

Sept. 20, 1996: Robert Sanderson is charged with three counts of first-degree murder, alongside Roger Sanderson (no relation) and Robert Tews.

June 1997 (six-week trial):

Robert Sanderson and both the co-accused men plead not guilty.

Crown prosecutor George Dangerfield argues the murders stemmed from a gang turf war over prostitution. A key piece of evidence: a hair found at the scene that a Crown expert witness said belonged to Robert Sanderson.

Defence lawyers argue the Crown’s key witnesses were not credible, saying Brent Stevenson was testifying in order to secure a deal. He was facing six separate outstanding criminal charges — all but one of the charges were later stayed.

June 27, 1997: All three men are convicted of first-degree murder after a six-man, six-woman jury deliberates for five hours. Each man receives a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment with no parole for 25 years.

March 1999: The Manitoba Court of Appeal dismisses an appeal put forward by Robert Sanderson. He was denied leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada later that year. What emerges at a separate hearing in 1999 for one of the co-accused men: the Winnipeg Police Service paid Stevenson $15,000 and relocated him outside of Manitoba after the trial.

2004: Advanced DNA testing proved the hair analysis — relied upon at trial — was wrong. The hair found on one of the victim’s feet at the crime scene did not belong to Robert Sanderson.

2017: Robert Sanderson submits an application to then-federal justice minister, Jody Wilson-Raybould, for a ministerial review of his case.

October 2018: Robert Sanderson requests bail pending the outcome of the ministerial review, but is denied.

2021: Robert Sanderson is released on parole.

February 2023: Then-federal justice minister David Lametti refers the case to the Manitoba Court of Appeal for a new appeal. Lametti says he is satisfied that “a miscarriage of justice likely occurred.”

— with files from Free Press archives

So Sanderson is cautious about getting his hopes up.

“Does it just sound good?” he wonders of Lametti’s decision to send his case back to the Manitoba Court of Appeal, though noting he is grateful for the boost of confidence. “Or is something going to be done about it?”

It seems Sanderson has come to terms with disappointments of his past, but frustration rises to the surface when he starts talking about his experience with Manitoba’s justice system.

“In my case, they wanted a quick arrest, a quick conviction dealt with,” he says matter-of-factly.

Sanderson was not ready to accept that fate.

“No, you’re not just going to throw someone in prison that’s wrongfully convicted … No, I’m not going to shut up,” he says. “I’m waiting for this to get resolved.”

LaFortune, Sanderson’s friend and mentor, joins him in the tent mid-interview. He has strong feelings about how the Manitoba justice system has treated his friend.

“My thoughts are just that the system is what it is. They don’t correct their wrongs,” LaFortune says.

“It’s just not right. They’re going to pat you on the ass and say, ‘Here’s some money, have a good day,’” he says, alluding to the payoffs other wrongfully convicted men have received.

“That’s just not right. What Rob was talking about is to correct some of the shit that’s been happening to not just him, but a lot of others. That’s a hard road and a long road.”

Sanderson thinks Dangerfield should face consequences. But he knows the lawyer has long since retired and is now elderly. The likelihood of such accountability is slim.

Sanderson believes there are systemic issues of injustice in Manitoba, including racism against the disproportionate number of Indigenous offenders in prison.

(According to Statistics Canada, Indigenous adults accounted for 27 per cent of admissions to federal correctional services in 2016-17 despite only representing four per cent of Canada’s population.)

There’s more Sanderson wants to say about the justice system, but he knows it’s not wise to spill everything on his mind to a reporter before his appeal sees the inside of a courtroom.

While he waits, his hope is for a new trial, rather than a stay of proceedings.

A stay doesn’t acquit him; he wants to hear the words “not guilty” and “you’re innocent.” He never again wants anyone to call him a “convicted murderer.”

“Being able to say I’m a free person,” he says. “That’s what I want back.”

Trevor Hagan / Winnipeg Free Press Robert Sanderson fears he won’t live long enough to see his case resolved.

He worries he might not live to see the case resolved. He recently suffered a heart attack.

While he doesn’t drink or use drugs, there’s the smoking — one cigarette after another throughout the three-hour long interview. He knows he should cut down.

And there are the things he knows he’ll never get back: precious time with his kids and grandkids in Manitoba; relationships with friends and family who died while he was in prison; the chance to form better connections with his Métis and Ojibwa community.

For now, he’s trying to stay focused on what he can control: his art.

He picks up a piece of wood and turns it over in his hands, thinking about what it could become.

katrina.clarke@freepress.mb.ca

Katrina Clarke

Investigative reporter

Katrina Clarke is an investigative reporter at the Winnipeg Free Press. Katrina holds a bachelor’s degree in politics from Queen’s University and a master’s degree in journalism from Western University. She has worked at newspapers across Canada, including the National Post and the Toronto Star. She joined the Free Press in 2022. Read more about Katrina.

Every piece of reporting Katrina produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.