Pulling back the veil

Residential school hockey tour masked suffering of Indigenous children

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/06/2025 (220 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Long ago, when hockey sticks were wood and goalies stopped pucks with naked faces, a kid named Kelly Bull and his Indigenous schoolmates played the game with such ardour they probably forgot all the ugliness of where they were.

Beyond the Rink tells the painful story, and tells it well, of Indigenous children taking temporary refuge in Canada’s game while enduring control, intimidation, fear, cruelty and deprivation at Pelican Lake Indian Residential School at Sioux Lookout in northwestern Ontario.

Well over 100 such schools, funded by the federal government and operated by religions, came and went over time between the 1800s and the 1990s. Bull’s school was Anglican.

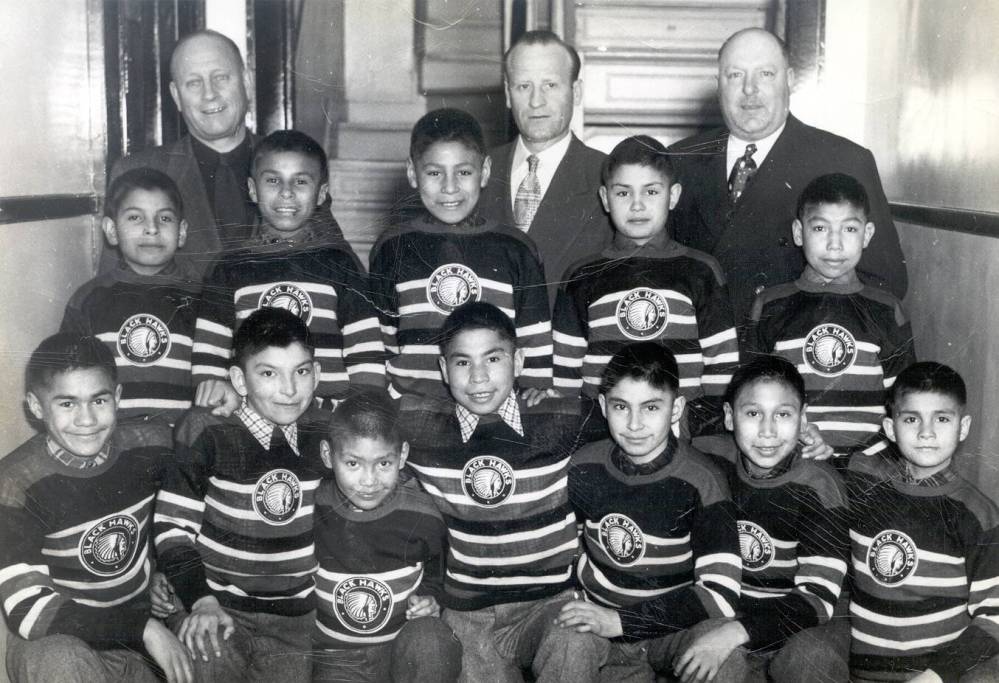

Western Archives and Special Collections, Western University

The Black Hawks (circa 1951-1952) with personnel, including (upper row, from left) Indian Agent Gifford Swartman, local businessman and volunteer Oreste Tintinalli and local businessman and booster Art Schade. The players pictured in the middle row (from left) are Lawrence Carpenter, Albert Carpenter, Kelly Bull, Ernest Wesley and Agrippa Beardy, and in the front row (from left) are Frank Wesley, Chris Cromarty, Lawrence Beardy, David Wesley, Walter Kakepetum, Henry Spence and Angus Wesley.

The Pelican Lake school was for Cree and Ojibwe kids from northern Ontario and eastern Manitoba. It was closed in 1969 after 40 years.

Beyond the Rink candidly documents these kids’ struggle for survival in the face of government-authorized cultural extinction. That’s what these boarding schools were there for: to kill the Indian in the kid. That’s what the government wanted.

The children were removed from their homes and communities, by force if necessary, and taken away to live in isolation, away from their culture, language and the comfortable self-image they knew. Usually, they were picked up at age seven and released once they turned 15.

In Bull’s school he was sexually assaulted by a male supervisor, a female supervisor and another student, and he knew you risked a beating if you spoke even one word of your traditional language, because he saw it happen twice.

These schools could be plain mean. At Pelican Lake one kid’s hockey skates were burned as punishment. Kids were strapped, punched and slapped.

Gar Lunney / Archives and Special Collections, Western Libraries, Western University

Black Hawks player Ernest Wesley (right) faces off against a player from an Ottawa team during the April 1951 tour.

The book is the work of Alexandra Giancarlo, Janice Forsyth and Braden Te Hiwi in collaboration with three of the players who were on the Sioux Lookout Black Hawks hockey team in 1951. It is about the team’s tour of Ottawa and Toronto the same year to show the country that residential schools were doing a good job of turning these Indigenous youngsters into what they defined as real Canadians. The three players were Bull, Chris Cromarty (since deceased) and David Wesley.

Giancarlo is an assistant professor in the faculty of kinesiology at the University of Calgary. Forsyth, of the Fisher River Cree Nation north of Winnipeg, is a professor in the faculty of education in the school of kinesiology at the University of British Columbia. Te Hiwi is now back in his home country of New Zealand.

About 150,000 children went through these schools, and an estimated 4,000 to 6,000 died because of the experience. The schools were poorly built, poorly heated and unsanitary.

Bull, who is Ojibwe, is quoted as describing an incident at the school that taught him a valuable lesson.

“I think the sermon the minister was preaching (in the chapel) was, ‘Love thy neighbour as thyself.’ Well, maybe that’s where I picked up being nice to people, until about an hour or so later (when) we were out in the playground… the principal happened to be walking around amongst kids playing. And he heard two boys conversing in Indian and you should have seen him. Boy, did he give it to them. And I stood there and I watched, and I said: ‘Holy smokes. What’s going on here? Here’s a guy that just finished telling us to love thy neighbour as thyself and he’s pounding the hell out of two defenseless boys.’”

Gar Lunney / Archives and Special Collections, Western Libraries, Western University

In this April 1951 photo, the Black Hawks are shown at the Chateau Laurier in front of a mural by C.W. Jefferys called Indians Paying Homage to the Spirit of Chaudiere.

Beyond the Rink studies the impact of these schools and their self-righteous attempts to gradually wipe out Indigenous beliefs and customs and turn the kids into assimilated Canadians. They also compelled Inuit and Métis kids to attend.

The book says “the entire residential school system was predicated on the assumption that Indigenous Peoples would not survive — in a cultural, if not literal, sense.” It goes on to say that residential schools were only part of the so-called solution — that the federal government also employed coercive instruments on Indigenous people, including “starvation, forced removal and the concentration of peoples onto small and isolated reserves, often away from fertile lands.”

One of the most bizarre moments in the book is of the kids at one Christmas dinner being “allowed” to speak “Indian.”

The objective of these schools is chillingly described around the time the Black Hawks are touring Ottawa and Toronto in 1951. To ensure the schools were successful in wiping out the Indian in these kids required “continuous and total isolation (‘ideally 24 hours a day and 12 months of the year’) from Indigenous culture and home communities.”

Says Black Hawks player Chris Cromarty: “The way the living conditions were. All the direction. We’re doing the same thing every day. Three meals a day. Three churches on Sunday. Going to bed at seven. Getting up at seven. All that kind of stuff. Doing chores on our hands and knees. They didn’t have mops as we have now, so you had to get on your knees with a scrub brush.”

Beyond the Rink

Giancarlo writes of the horrible catch-22 faced by the kids after their time at the school: “Some of the Black Hawks had died ‘horrible deaths’, as Kelly says, mere decades after leaving school, spat out by a colonial system that annihilated their identities as Indigenous people, yet left them unequipped to survive in the white Canadian world.”

Barry Craig is a retired journalist.