Overhaul upheaval Transit overhaul created significant gaps in service, hitting low-income areas and bus-dependent populations hardest: Free Press/Narwhal analysis

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

When transit flows, a neighbourhood thrives.

When buses are frequent, arrive on time and run into the night, it means more kids make it to after-school activities, more students can get to class on time, more shift workers can get home safely late at night and more commuters can leave their vehicles at home.

The end result is robust movement throughout a community, according to Orly Linovski, an urban planning professor at the University of Manitoba.

That was the vision Winnipeg Transit promised as it rolled out its all-new Primary Transit Network earlier this summer.

The new routes and redistribution of bus stops implemented as part of the transit-system overhaul were intended to deliver faster and more reliable service to better serve all corners of a growing city.

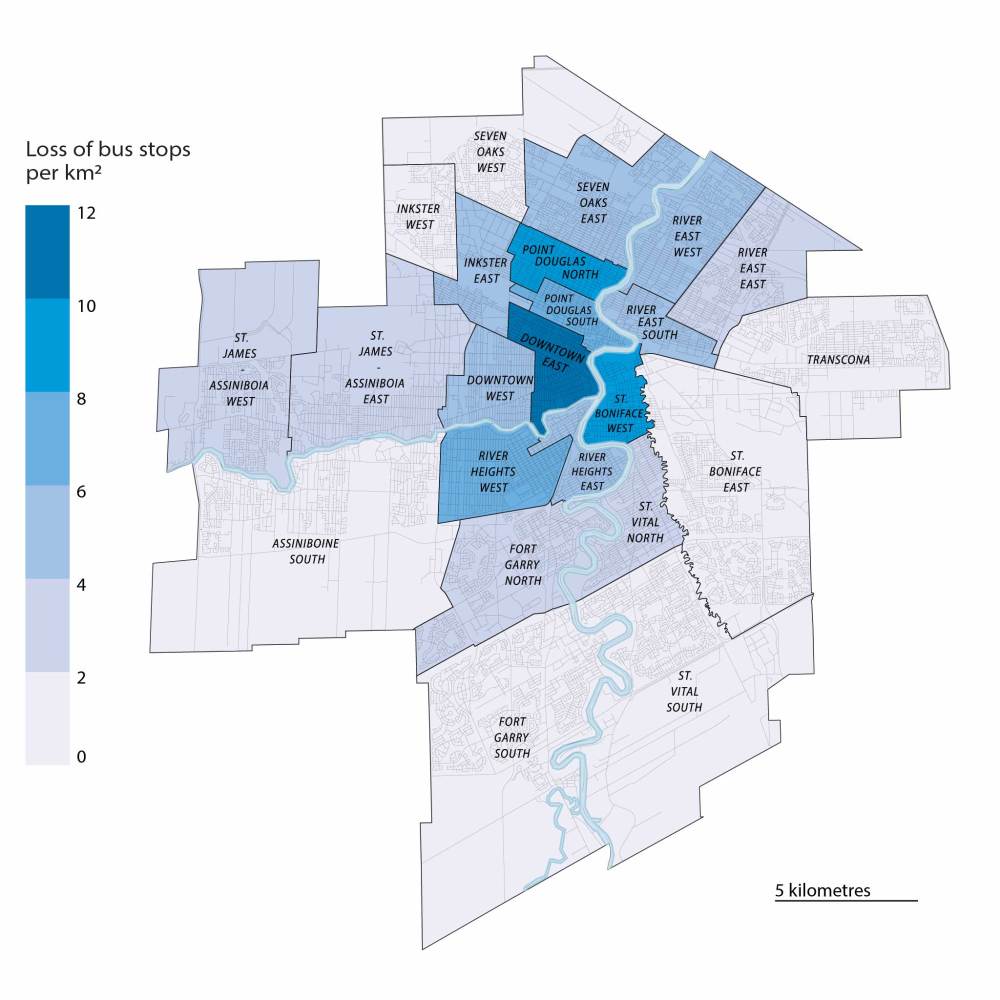

A Free Press/Narwhal analysis of the city’s transit system before and after the June 29 transition date reveals a different story.

The old system’s 87 routes and 5,100 bus stops have been stripped down to 71 routes and about 3,800 stops.

Despite adding a few hundred new stop locations, particularly in fast-growing neighbourhoods along the city’s outskirts, Winnipeg Transit ultimately cut a quarter of the locations where passengers can board a bus.

And the impacts are most stark in the neighbourhoods that need transit most.

The analysis shows historically underserved communities in the downtown, North End and West End neighbourhoods have lost up to three times as many bus stops as the rest of the city and have seen significant reductions in late-night bus service.

(See still images of the maps in the animation above: “before/old network” map and “after/current/new network” map.)

Bjorn Radstrom, Winnipeg Transit’s manager of service development, said the cuts are part of a “balancing act” needed to modernize the transit system.

The new network is the first stage of the city’s transit master plan — a 25-year road map toward a more efficient system, modelled after big-city subway networks, that will encourage more riders out of their cars and onto the bus.

Methodology

The Free Press/Narwhal used schedule and route data from the General Transit Feed Specification, a standardized and open-source transit database, along with stop locations provided by the City of Winnipeg to analyze how bus stop spacing and service access has changed within city neighbourhood boundaries.

Net changes in bus stop density were calculated using mapping software QGIS’s spatial analysis functions.

Demographic data for each neighbourhood comes from the 2021 Canadian census and is made available by the city.

“It was all done for a reason,” Radstrom said in an interview earlier this week.

“There was definitely a decrease in the number of bus stops, but that doesn’t translate into worse service. The thing that makes a difference to people is, how frequently does the bus come and how reliable is it?”

Modal shift — getting a motorist to take the bus, walk or bike — has a clear environmental benefit: reducing emissions and air pollution and improving public health.

Kyle Owens, president of advocacy group Functional Transit Winnipeg, calls transit a “solved problem,” but only on paper, not in practice.

“Great transit does not solve climate change, great transit does not eliminate poverty, great transit does not transform your city into an affordable, fun place to live,” he said.

“But if you want to make progress on any of those things, any amount, you need great transit first.”

Two-and-a-half months into the changeover, some Winnipeggers are reporting the frequency of bus service has improved and they are now able to access a nearby bus stop for the first time.

But they are in the minority. Complaints, Radstrom said, far outweigh the compliments.

Many users have described longer travel times, more transfers and the loss of their usual route home from an evening shift as late-night stops have disappeared.

All this was before the start of the new school year, when thousands more users are testing out the new system for the first time.

University of Manitoba Students’ Union president Prabhnoor Singh has three words to describe the transit transformation: “a complete disaster.”

His own one-way commute from his home in north Winnipeg to the university has jumped from one bus and 60 minutes to a nearly two-hour journey with three transfers.

Now, he chooses instead to drive 40 minutes to get to campus.

“It just shows you how much of a difference this has created, and overall, we haven’t heard much positive responses from our students,” he said.

Liberal MP Kevin Lamoureux (Winnipeg North) said he’s been fielding phone calls, e-mails and questions from stressed constituents since the overhaul.

“One of my constituents actually got his driver’s licence and got a truck because of the bus changes,” Lamoureux said in an interview following a town hall in his riding last month, adding residents have expressed a “very real … anxiety” about the new system.

Lamoureux describes his riding as largely working class, filled with students and an above-average concentration of young people.

It also houses some of the neighbourhoods found to experienced above-average stop losses.

“One of my constituents actually got his driver’s licence and got a truck because of the bus changes.”

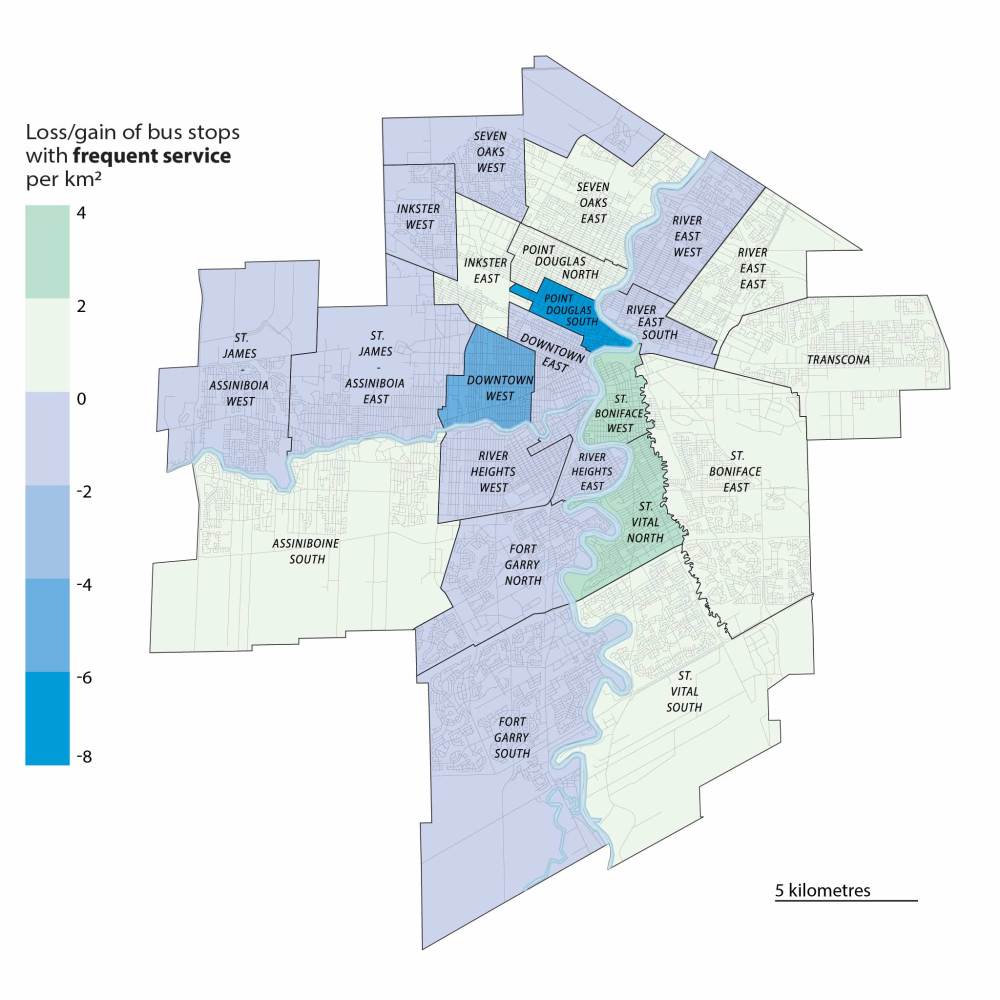

Before the overhaul, Winnipeg had about 11 bus stops per square kilometre. That’s dropped to about seven stops per square kilometre city-wide, according to the Free Press/Narwhal analysis.

The city cut about 2.5 stops for every square kilometre, but those changes weren’t made evenly.

Downtown and North End neighbourhoods — especially Point Douglas and Inkster — lost between two and three times as many stops as the city-wide average, while suburbs like Transcona and Fort Garry South, which have grown rapidly in recent years, saw the fewest stops removed.

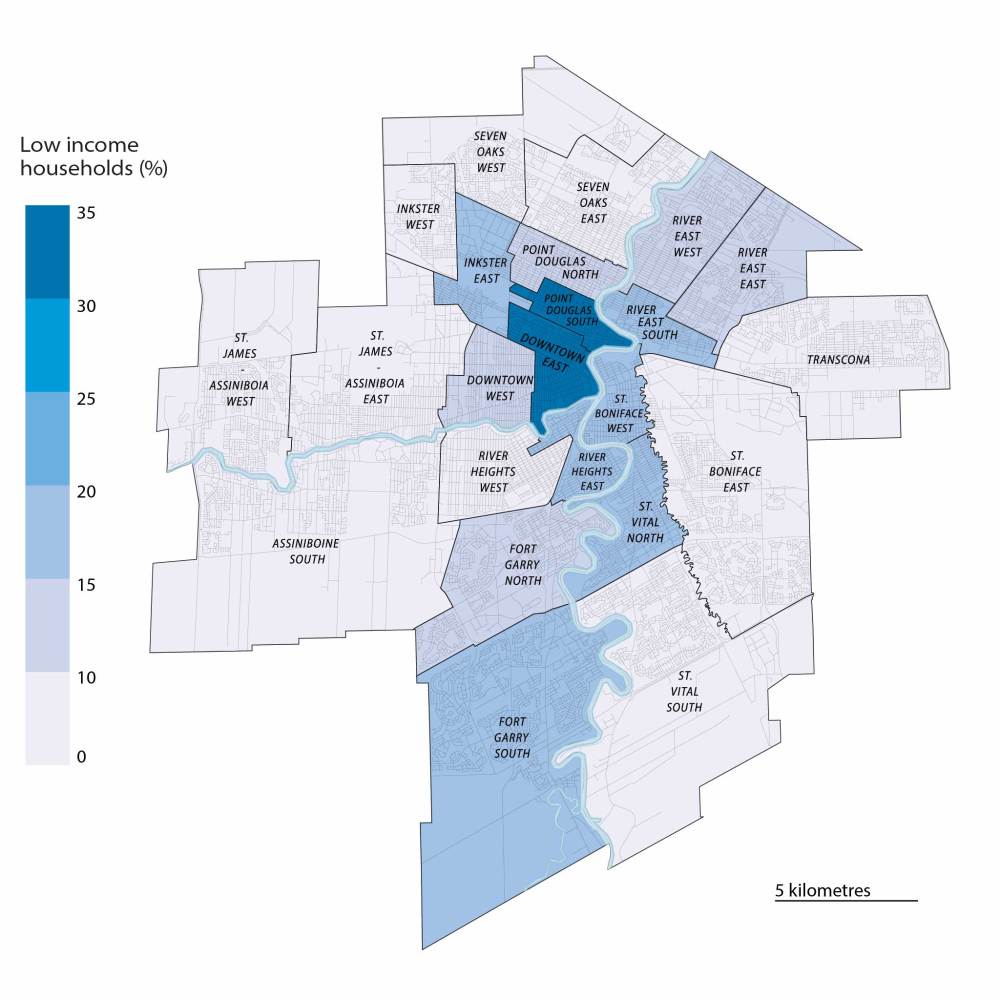

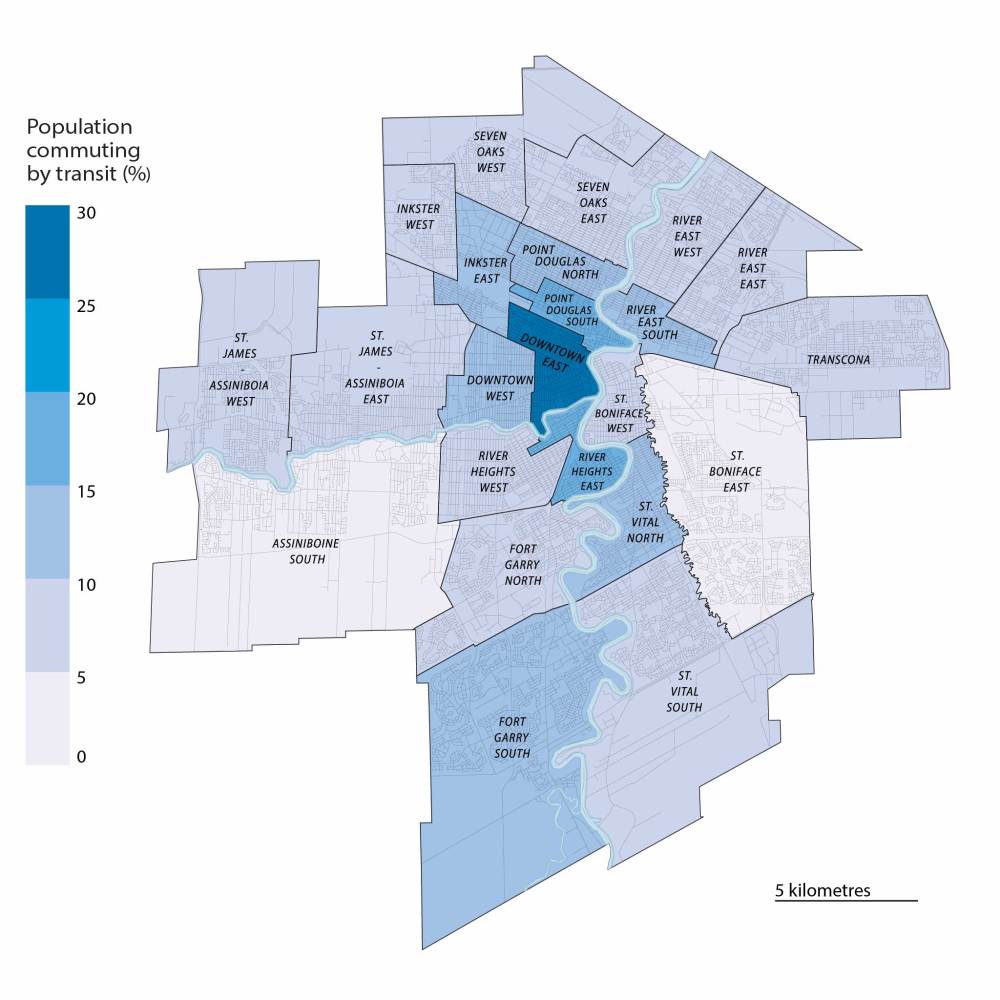

Linovski, the urban planning professor, finds it “especially problematic” that the areas with disproportionate cuts to stops seem to overlap with the neighbourhoods where transit is needed most — namely communities with more low-income families and higher rates of transit use.

Families in Downtown East, Point Douglas South, Inkster East and River East South (Elmwood) are more likely to rely on transit for daily commuting and more likely to fall below low-income thresholds.

All four of those neighbourhoods saw above-average stop losses.

While Linovski recognizes Winnipeg Transit had two distinct goals — to better serve people taking transit, and to encourage people with other commuting options to hop on the bus — she notes those two goals “can be in conflict.”

Encouraging drivers to try other transportation would require a “major investment in funding,” she said.

The full transit master plan upgrades are expected to cost between $540 million and $1.1 billion over 25 years, and will receive contributions from all levels of government.

The city is hesitant to restore stops, noting the annual cost to replace one bus stop on the new, high-frequency routes is nearly $22,000. Replacing all of the stops removed from those routes would cost close to $4 million.

But, as the cost of living continues to rise, improved transit service will become more necessary in neighbourhoods currently feeling left behind, Linovski said.

“We have a duty in terms of human rights to make sure that people have access to their daily needs, health care, education, employment,” she said. “That is part of the values of Canada.

“I often don’t see transportation linked to that.… People have a right to be able to get to the places they need. And for many people in our city, increasingly, that is not going to be by driving.”

While Radstrom acknowledges many of the most affected neighbourhoods are among the city’s oldest and, in some cases, the poorest, they were also areas where there hadn’t been a thorough review of the “legacy” of accumulated stops requested by councillors and businesses.

“If that’s been ongoing since the 1940s (or) the 1950s with more and more stops being added for various reasons that nobody ever documented … you end up with much more closely spaced stops in some of the older areas.”

Radstrom said the cuts in those neighbourhoods were designed to emulate the light-rail transit and subway systems that inspired Winnipeg’s new route layouts. Better spacing creates smoother, faster service, he explained.

“When people are more reliant on transit, they value much more the frequency and reliability of a service that has bus stops that are spaced properly,” he said.

The new system has, for the most part, improved access to frequent routes where buses arrive every 15 minutes or less; analysis shows the proportion of stops served by these routes increased from 13 to 17 per cent.

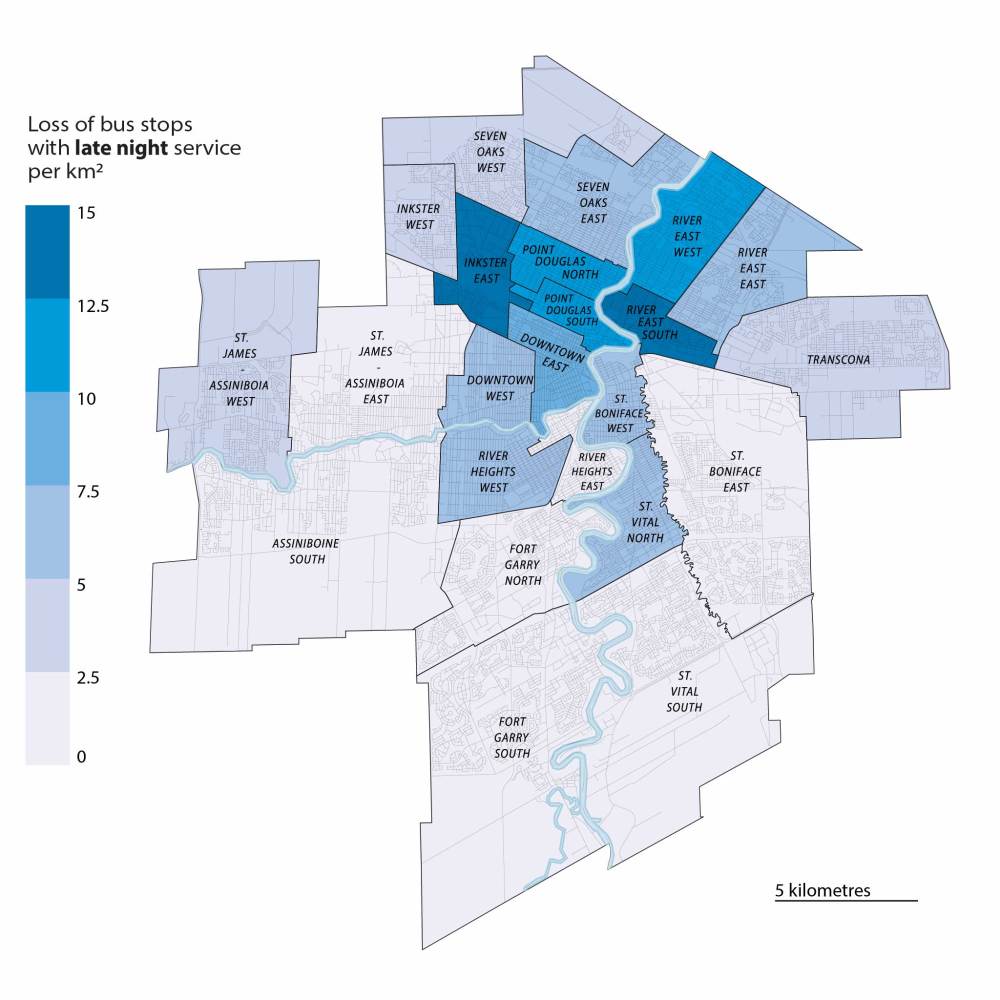

Frequency isn’t the only measure of accessibility that matters to transit users.

More than half of all bus stops were still accessible after 11 p.m. under the old system; now only one-third are.

The city’s north side has been hit the hardest, where as many as 15 stops with late-night service have been removed per square kilometre compared to a city-wide average of 5.5.

Singh, the students’ union president, said he’s heard students are forced to leave class early because there isn’t a late-night bus available. The students’ union, which represents 27,000 members, is planning to meet with city representatives to raise its concerns.

“It’s unfortunate that most of them won’t get good bus service,” he said of the union’s members.

Coun. Ross Eadie (Mynarski) has fielded calls from constituents — notably seniors — who say the removal of bus stops in his North End-area ward has made accessing transit more dangerous.

Fewer stops means longer walks to bus stops through one of the city’s most notorious neighbourhoods.

“If you have to get a bus after 10:30 (p.m.), you’re not walking down Selkirk Avenue, or any street around there, all the way up Mountain (several blocks to the north),” he said.

“It’s very dangerous. I’m really angry about that.”

“I think it’s going to be overwhelming this winter.”

While the city’s on-demand bus service is available to bridge those gaps, Eadie questions whether it will be able to keep up.

Winnipeg Transit’s on-request bus service — which allows riders to request a bus pickup online, via an app or by calling 311 — began as a pilot project in 2021, but was expanded with the Transit overhaul to 12 zones around the city where riders can request a bus to take them from where they are to a bus stop on the primary network.

(Transit Plus continues to provide door-to-door service for registered riders with accessibility needs.)

“Is (Transit) ready for all the seniors who are going to be applying for (on-request) trips?” Eadie said. “I think it’s going to be overwhelming this winter.”

Radstrom acknowledges there have been “challenges” with the new system’s implementation. A “minor rewrite” of some routes to improve arrival times has already happened and a more thorough review will occur in December.

“The service that’s in place now is going to be a bit better than we saw during the summer, but right now we’re undergoing a complete comprehensive rewrite of those schedules, because it’s not good,” he said.

“The buses are consistently late and we have to address that. We also have the reverse problem, where through this bus stop balancing, some routes are operating faster than we expected … which is also not a good thing.”

It’s not yet clear whether the changes are having the desired effect. Ongoing problems with GPS tracking on buses, notably involving downtown routes, is impacting the city’s ability to assess ridership data. The issue surfaced within two weeks after the launch.

“Until we fix that, which is hopefully coming soon, I can’t really say exactly how ridership is doing,” Radstrom said.

There will be alterations, additions and other shifts in service every year, he added, in pursuit of a transit system that is frequent and accessible to as many people as possible.

“By no means do we think we got everything right, right out of the gate. We know that changes are going to be needed.”

Owens, the transit advocate, is hopeful. The new system makes adding routes and stops easier than before, and further expansion is possible so long as there’s political will and the inclination to increase the transit budget.

“The basis of the transit master plan, to triple the number of Winnipeggers with access to frequent service and to lay the foundation of a new structure for transit, for expansion in the future, has happened,” he said.

“What happens next is really something that we have to decide together.”

julia-simone.rutgers@freepress.mb.ca | malak.abas@freepress.mb.ca

Julia-Simone Rutgers is a climate reporter with a focus on environmental issues in Manitoba. Her position is part of a three-year partnership between the Winnipeg Free Press and The Narwhal, funded by the Winnipeg Foundation.

Malak Abas is a city reporter at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg's North End, she led the campus paper at the University of Manitoba before joining the Free Press in 2020.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, September 5, 2025 6:38 AM CDT: Corrects references to on-request service and to Transit Plus