How winemakers get all those tiny bubbles in the bottle

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

When the Winnipeg Wine Festival pops the cork on two days of swirling, sniffing and sipping at the RBC Convention Centre next weekend, it will once again feature a theme, which usually involves highlighting a wine-producing country or region. Last year featured the overarching “wines of Europe” theme, while this year organizers have eschewed place in favour of tiny bubbles, with sparkling wine taking centre stage.

Not all sparkling wine is created (or priced) equal, of course, with the gamut running from cheap, CO2-injected concoctions to fine French champagne.

One of the main differences in how sparkling wine is made is how and when the bubbles enter the equation. Most sparkling wine on our shelves is made using a secondary fermentation, which is how the wine becomes carbonated.

In Champagne they use what is called the “traditional method,” previously called the “champagne method” until producers in that region of France objected to the word “champagne” appearing on wines from other regions and countries.

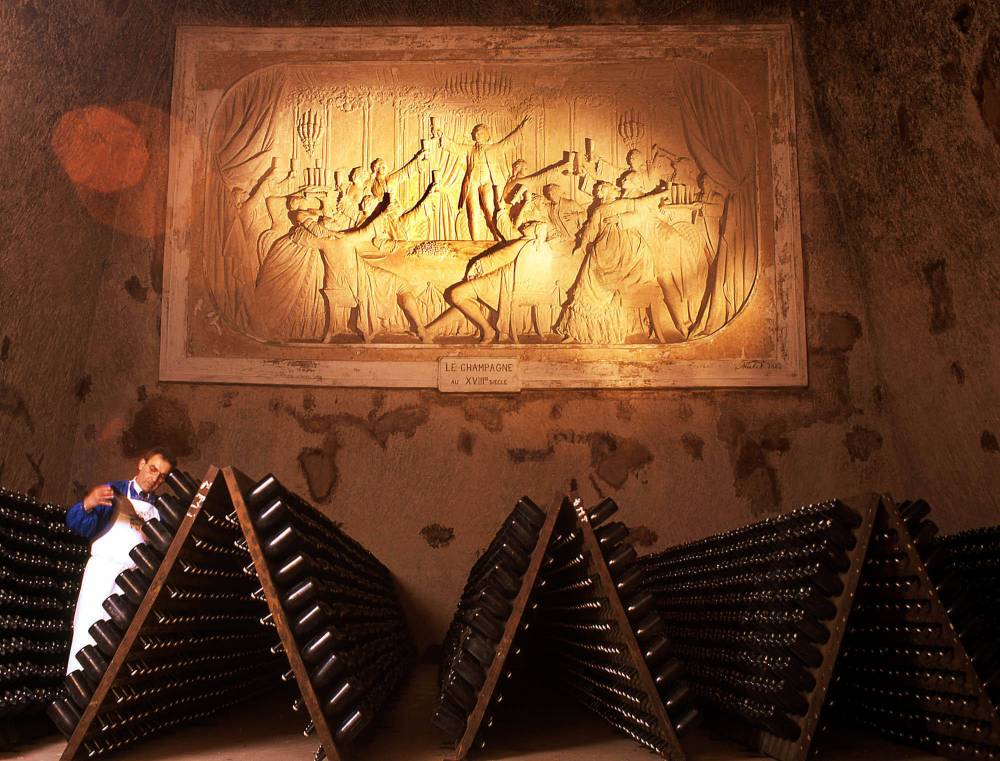

Michel Spingler / Associated Press files During traditional method sparkling wine production, as seen here at champagne producer Pommery in Reims, bottles are racked in an inverted position and occasionally gently shaken/twisted in a process called riddling, which sends the spent yeast cells towards the bottle’s neck. The neck is then frozen, the plug of dead yeast cells removed, and the bottles topped up and re-sealed.

For traditional method bubblies, a still wine is made in the typical method before being bottled and sealed under crown cap, with a small amount of sugar and yeast added. The addition starts the secondary fermentation, with sees the yeast convert the added sugar to alcohol and releasing carbon dioxide, which is trapped in the bottle and creates carbonation. Once the yeast has done its work, the dead cells remain in the bottle for a time to add texture to the finished wine.

To remove the dead yeast cells, bottles in the cellar are inverted and riddled — gently shaken or twisted, traditionally by hand but increasingly by machine — which sees the dead yest cells gather near the mouth of the bottle.

The neck of the bottle is then frozen, the crown cap removed and the plug of dead yest cells taken out before the wine is topped up with a bit more wine, called a dosage. It’s then re-sealed, typically under the flanged cork and wire seen on most bottles on store shelves.

Champagnes, Spanish cava, crémants and many other better-quality bubblies are made using the traditional method, which will typically be indicated somewhere on the label.

A less labour-intensive and less time-consuming way to make sparkling wine is called the charmat method. Again, a still wine is created before being the whole batch is transferred to a pressure-resistant tank, into which yeast and sugar are added. The tank is then sealed, secondary fermentation gets going, and the CO2, which can’t escape the tank, creates bubbles.

The tank of bubbly wine is then sent through a filter to remove the dead yeast cells, and divvied up into bottles. This is how your favourite bottle of cheerful Prosecco is made, along with Lambrusco and many other less pricy bubblies.

There’s also the option of simply injecting CO2 into still wine before bottling, but that’s only really employed for very inexpensive sparkling wines or fizzy wine-based concoctions. We don’t need to talk about that.

Another way of making sparkling wine that’s seen an increase in popularity alongside the minimal-intervention, natural wine movement is what’s called the ancestral method, which is thought to be the oldest way to make bubbly (hence the name).

A winemaker will begin making a still wine, and about halfway through fermentation — the conversion of sugar to alcohol — the lower-alcohol still wine is filtered (sometimes) and chilled to halt fermentation. After some months, the wine is bottled and allowed to warm up. As the temperature rises the primary fermentation restarts, completing the sugar-to-alcohol conversion and creating carbonation that, like in traditional-method wines, remains trapped in the bottle.

The bottles are then chilled and riddled, the neck of the bottle frozen and the plug of dead yeast removed, although unlike traditional-method bubblies there’s no dosage. Bottles are then capped and left to settle for a bit before release.

If you’ve ever had a “pet-nat” (short for pétillant naturel in French, which translates to “naturally bubbly”), this is how it’s made. A warning: ancestral method sparkling wines can sometimes be a bit volatile as they’re being opened, so be sure to pop that cork over a sink or with a towel nearby.

There will be dozens of sparkling wines of all styles poured throughout this year’s Winnipeg Wine Festival, many of which are being brought in just for the fest. To find your new favourite fizz, grab tickets at wfp.to/winefest.

uncorked@mts.net

@bensigurdson

Wines of the week

Codorníu NV Cuvée Clasico Brut (Cava, Spain — $16.99, Liquor Marts and beyond)

A nearly even split of indigenous Macabeo, Xarel-Lo and Parellada grapes, Codorníu’s entry-level Cava is pale straw in appearance, and aromatically brings bright lemon-lime, green apple, chalky and herbal notes on the nose. This traditional method sparkling is nearly bone dry and light-bodied, with zippy bubbles bringing tart citrus and green apple flavours alongside a chalky note and a medium-length lingering finish. A candidate for sparkling wine cocktails, but quite tasty on its own as well. 3.5/5

Acquesi NV Rosato (Piemonte, Italy — $19.99, Liquor Marts and beyond)

A blend of red Barbera and Dolcetto grapes, this rosé bubbly in eye-catching floral packaging is pale pink in colour, offering modest floral, strawberry leaf, raspberry and subtle chalky notes. It’s light-bodied and just off-dry, with lively bubbles bringing red berry flavours alongside peach candy, lemon zest and chalky notes. Made using the charmat method, it’s simple but pleasant, and would work well in a mimosa or sparkling wine cocktail. 3/5

Domaine Leroc NV Roc’Ambulle Rosé Pet Nat (France — around $31, private wine stores)

This minimal-intervention, ancestral method sparkling wine is made from the red Negrette grape; it’s raspberry red in colour and brings tart plum and cherry aromas as well as raspberry candy and lime zest aromas. Bone dry and light-plus bodied, all those tart red fruit notes come with lively effervescence, a hint of tannin from the grape skins, medium acidity and a modest finish (it’s 10.5 per cent alcohol). A fun adventure — but it’s quite fizzy, so open over the sink. Available at De Nardi Wines, Ellement Wine + Spirits, Kenaston Wine Market, The Pourium and The Winehouse. 4/5

Champagne Canard-Duchêne NV Charles VII Blanc de Blancs (Champagne, France — $69.99, Liquor Marts and beyond)

“Blanc de Blancs” indicates this French champagne is made solely from the Chardonnay grape, sourced in this case from the Côte des Blancs region of the iconic appellation. It’s medium straw in colour and offers a lovely nose of bread dough, red apple, pear, fresh-cut flowers and toasted nut. On the dry, medium-bodied and elegant palate, those flavours work harmoniously, with apple, bread dough and lemon curd notes, with secondary chalky and nutty notes adding texture and a lingering finish lengthened by fine effervescence. If you’ve never tried champagne or are looking for a deal, it’s worth grabbing this tasty, complex example before the end of September while it’s on sale (it’s regularly $79.99). 4.5/5

Ben Sigurdson

Literary editor, drinks writer

Ben Sigurdson is the Free Press‘s literary editor and drinks writer. He graduated with a master of arts degree in English from the University of Manitoba in 2005, the same year he began writing Uncorked, the weekly Free Press drinks column. He joined the Free Press full time in 2013 as a copy editor before being appointed literary editor in 2014. Read more about Ben.

In addition to providing opinions and analysis on wine and drinks, Ben oversees a team of freelance book reviewers and produces content for the arts and life section, all of which is reviewed by the Free Press’s editing team before being posted online or published in print. It’s part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.