Pillow talk

Smith’s gen-Z characters navigate pitfalls of work, sex and alienation

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

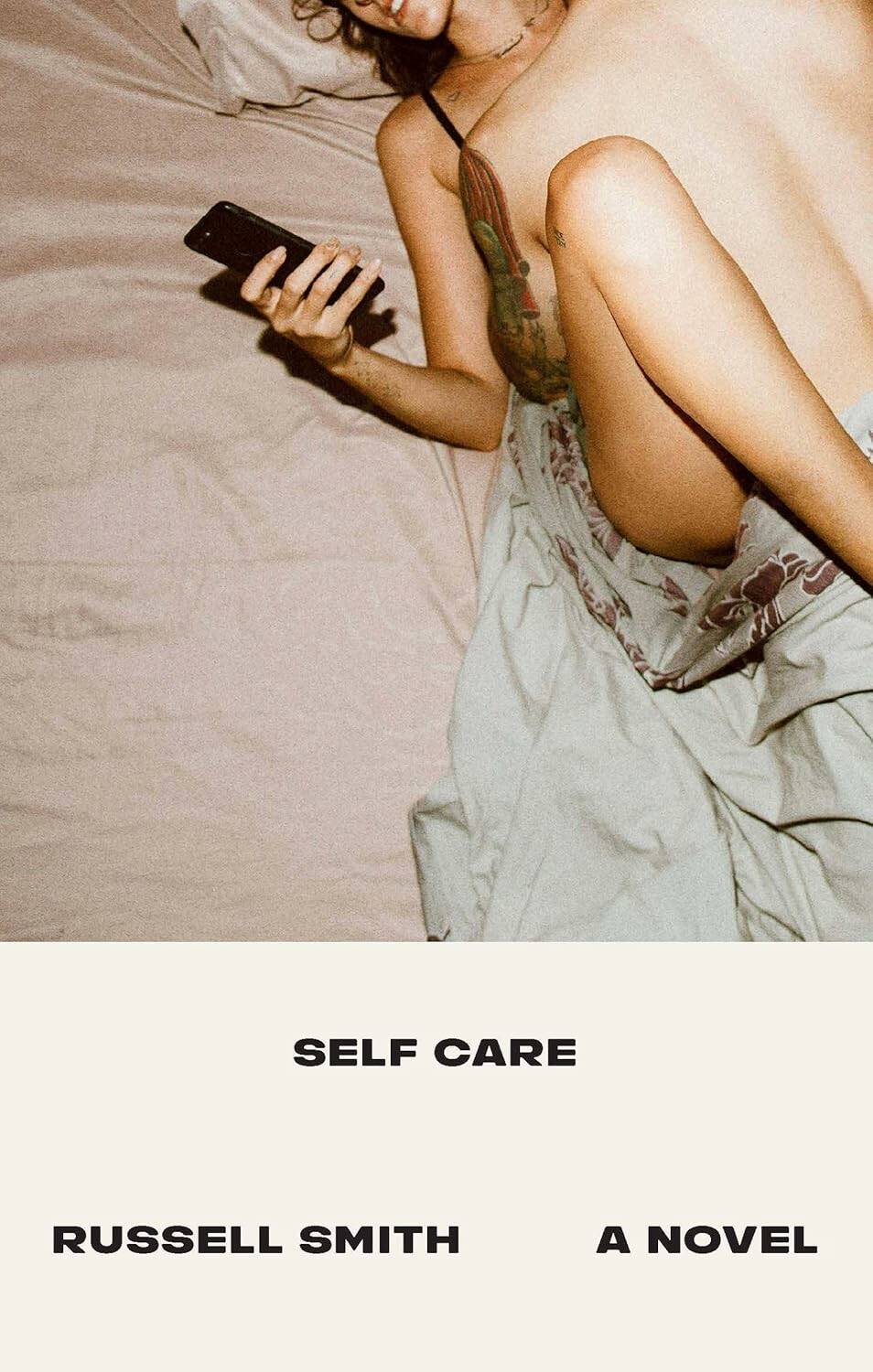

Self Care, Toronto writer Russell Smith’s first novel in 15 years, is bound to make some readers bristle.

In it, the 62-year-old author of How Insensitive and Girl Crazy takes a quasi-satirical look at gen Z, portraying it as an aggrieved generation overdiagnosed with and overmedicated for mental illness, having lots of sex but taking little joy in it.

Of course, it’s a writer’s prerogative to put himself in the shoes of characters who are nothing like himself (though Smith has not historically done so), but when choosing to satirize the complicated lives and unique loneliness of a generation so far removed from his own, he opens himself up to accusations of, at best, a kind of “old man shakes fists at clouds” obliviousness or, at worst, the snide condescension of privilege.

These fears are not entirely misplaced. However, Smith often accurately and anthropologically puts his finger directly on the throbbing purple bruise of modern discontent, disaffection and alienation.

While Smith skewers a lot of gen-Z stereotypes — he’s particularly hard on the widespread use of both mood stabilizers and self-help bromides — Self Care isn’t just poking fun. It is also, in many ways, deeply sympathetic to its characters, who are struggling with a world very different from the ones their parents grew up in.

They are dealing with the fact that a university education is no longer a ticket to the usual markers of success; with the inescapable force of social media, which rewards appearances over accomplishment; with echo chambers that reflect their own beliefs endlessly back at them, stifling growth or change.

The novel’s protagonist, a 20-something journalist called Gloria, pens a weekly self-care column for a website called the Hype Report, though, clearly depressed and unsatisfied, she seems highly inexpert in taking care of herself.

It’s a tenuous, ill-paid job — she lives with a roommate in an apartment in an undesirable neighbourhood — and her boss is now asking her to cover a rash of suicides among arts workers in the city.

Her boyfriend (if you can call him that), Florian, is a handsome, jerky bartender who’d rather scroll his phone than have a real conversation. Her best friend is having an affair with an older married man and posts semi-nude selfies on Instagram to boost her self-esteem.

After Gloria makes an uncharacteristic overture to a young man taking part in a fascist demonstration, she finds herself drawn into a potentially dangerous relationship.

Daryn is part of the online incel (involuntary celibate) community, a misogynist movement that encourages men to blame women for their own inability to attract partners. That aside, he’s also just not her type.

With a deft touch and authentic dialogue, Smith explores the slippery notion of sex and attraction among people who are outwardly ambiguous about traditional relationships and who seem averse to exploring grey areas.

Russell Smith photo

Russell Smith… TK

Gloria wants to hate Daryn — for his politics, obviously, but also for his dumb, uncool runners, his pathetic eagerness, his malleability. But she’s also aware she dislikes Florian for exactly the opposite reasons — his performative allyship, his hipster scarves, his aloof see-you-when-I-see-you lack of commitment.

And Florian has actively tried to hurt her, under the guise of erotic choking during sex, while Daryn is passive and gentle in bed, resulting in her taking on a dominant role that turns increasingly aggressive.

Smith also cannily parallels the paradoxical ways attractiveness is valued in men and women. Daryn considers himself ugly, and uses this to justify his rage at the shallow women who won’t date him; it’s a classic catch-22. Gloria dismisses the validity of his feelings, but struggles with insecurity about her looks, in a culture that tells her to love herself while holding up countless examples of bodies thinner than hers.

When he tells her she’s beautiful, it makes her feel as if a knife had gone in her “and given her a familiar warmth and then a familiar pain, a consciousness that she was not beautiful enough and must not think about that, for it was unhealthy and of course she was fine as she was…”

There’s a queasy sense of impending doom in Self Care that echoes the way the world feels now, especially to younger people — a sense that there’s no way out of a downward spiral. The novel’s conclusion, while not unexpected, is shocking in its sadness and inevitability.

Jill Wilson is the Free Press Arts & Life editor.

Jill Wilson is the editor of the Arts & Life section. A born and bred Winnipegger, she graduated from the University of Winnipeg and worked at Stylus magazine, the Winnipeg Sun and Uptown before joining the Free Press in 2003. Read more about Jill.

Jill oversees the team that publishes news and analysis about art, entertainment and culture in Manitoba. It’s part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.