World’s fastest pianist keyed up for homecoming

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Arguably the world’s fastest pianist is from Winnipeg.

“I played a lot of football when I was in (St Paul’s) high school. Kelvin was always beating us,” says Lubomyr Melnyk, referring to the alma matter of Neil Young, who, at 80, is four years older than Melnyk.

It’s hard to imagine the diminutive, mystically inclined (and mystically bearded) Melnyk — whose references move quickly from Young to Joseph Haydn, Plato to Martin Heidegger — as a jock.

But it’s also hard to imagine him, or anyone for that matter, playing 19.5 notes per second in each hand, as he did in 1985, setting a practically athletic world record.

Is this a gimmick? How Melnyk explains his unique ability, advertised amid many capital letters and exclamation marks in his marketing materials, may help answer this question.

“The continuous technique is actually a metaphysical technique, akin to martial arts, so that when you generate and make it active, your entire body becomes a spiritual energy motor,” he says.

“The greatest classical pianist will never surpass 14 notes … The continuous pianist does over 19 … this is really a revolutionary new world of the piano.”

If this sounds like braggadocio dressed up in new age hokum, take the time to listen to Melnyk’s self-played compositions (which number more than 24 albums).

There is not a hint of cynicism his music, which bursts with longing for the transcendent.

While the motion is fast, the movement across harmonies is gradual, evoking a bird soaring over undulating landscapes, sunny here, shadowy there.

It’s this flowing aspect which helps to give the “continuous” name to the sound Melnyk has developed. (His second world record is for playing between 13 and 14 notes per second continuously for more than an hour. Many of his works have this quality in miniature — dizzyingly quick loops which gently evolve over 10 to 20 minutes.)

“Classical pianists think they can play the advanced pieces (of mine), and they cannot. They cannot even begin. A piece like Windmills will never, never be accessible to even the greatest classical pianist in the world. Never. We can go for 5,000 years,” he says.

Melnyk’s nose-thumbing at the classical establishment doesn’t stop there; it feels more defiant than cocky when you consider how it’s neglected him. He can sell out the Barbican Centre in London, U.K., but he’s not playing with its house band, the London Symphony Orchestra.

No matter: he’s developed a listenership that far exceeds most touring concert pianists and accolades from several well-placed critics. The Guardian awarded his album Rivers and Streams five stars, while Pitchfork praised his album KMH in a review that placed him in the minimalist tradition.

The comparison is inviting for a number of reasons, not least of all minimalism’s embrace of bearded mystics with a thing for arpeggios, from hirsute American composers Terry Riley and Moondog to Estonian Arvo Pärt.

But Melnyk feels the minimalist label, in his case, is based on misunderstanding.

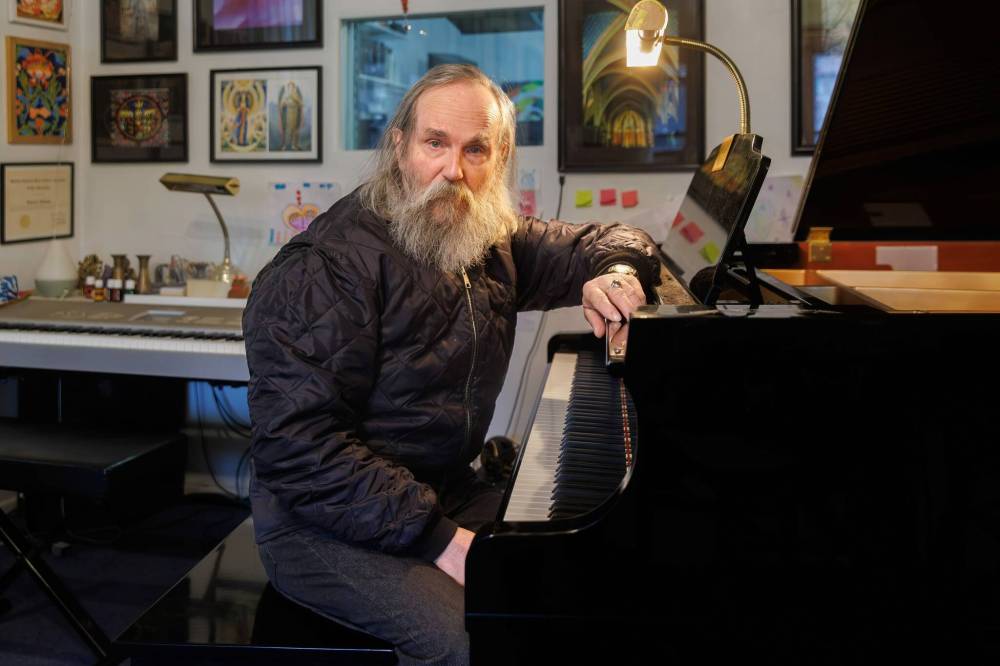

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS

Lubomyr Melnyk set a world record in 1985 by playing 19.5 notes per second on the piano.

“To some extent, my music is a fusion of Joseph Haydn and (New York minimalist) Steve Reich in its origins. Now, Steve Reich has fallen away. Joseph Haydn remains,” he says.

Still, talk to him about Erik Satie — the proto-minimalist who walked the streets of Paris with a pet lobster on a leash, invented his own religion and developed an enduring cult following years after the music academies and establishment dismissed him — and he appears to light up.

Another artist who intrigues him is Lenny Breau. The late Winnipeg jazz guitarist died in relative obscurity, despite pioneering or mastering exceedingly difficult techniques and earning a rep among the likes of Chet Atkins and Randy Bachman as one of the best to ever pick up a six-string.

“How many world-class musicians have come out of this little city? (The 1960s and ‘70s were also) a phenomenal age and produced phenomenal musicians,” he says.

Melnyk, who left Winnipeg for Paris in the early 1970s, lives today in a small Swedish village in the middle of a forest, according to Ervin Bartha of ClearLightSound, the concert’s presenter.

The nomadic musician with Ukrainian roots performs all over the world, and arrives to Canada after performing in Oxford, England. Several of his performances in Ukraine from the past decade can be found on YouTube (typically with an ecstatic comment section), and Melnyk links his music to his identity, saying, “This music would not exist at all if I were not Ukrainian.”

He visits Winnipeg, which evidently has not yet fully recognized him as one of its own, only occasionally these days to perform and record with Bartha.

All the more reason to see Melnyk, one of Winnipeg’s most original musical sons, on Sunday.

conrad.sweatman@freepress.mb.ca

Conrad Sweatman is an arts reporter and feature writer. Before joining the Free Press full-time in 2024, he worked in the U.K. and Canadian cultural sectors, freelanced for outlets including The Walrus, VICE and Prairie Fire. Read more about Conrad.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.