As a wildfire closed in, a mandatory evacuation was ordered for Leaf Rapids in late July. It would be two months before the 350 residents could return.

When reporter Nicole Buffie visited the northern community a short time later, she discovered the fire was just one of many blows the former mining boom town has endured in recent years.

Fifty years ago, following the discovery of vast mineral deposits, Leaf Rapids was designed and built in a span of four years and heralded as the town of the future. Today, it's hanging by a thread.

Life in a dying town Summer wildfire threat was the latest nail in the coffin for once-prosperous Leaf Rapids

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

LEAF RAPIDS — Travelling north of the 56th parallel along Provincial Road 391, the boreal forest occasionally thins to showcase where lake meets sky. Ravens patrol the air, pausing to swoop down to inspect the region’s flora, which is visibly scarred by fresh and historical wildfires. On a recent October morning, the changing colours of coniferous trees evoke flames dancing on the water.

Green highway signs direct drivers to Leaf Rapids, situated some 230 kilometres northwest of Thompson along a winding gravel road. Tattered banners fastened to street-light poles at the town’s entrance promise visitors it’s a “a great place to be!” but the people who have spent time here have differing views.

The town’s Facebook page has one review, from 2024, and the reviewer does not mince words.

“This place blows. Don’t bother,” the author advises.

Throughout town, the roads show their age, and unruly brush closes in on some corners.The streets seem abandoned and almost post-apocalyptic when you drive through the once bustling mining town of nearly 2,400 people. A group of teens playing hooky from school and an occasional dog are signs of life, but most neighbourhoods have boarded-up bi-level homes — doors kicked in, windows smashed out and yards littered with garbage and broken appliances.

On the occasional house, nailed-up signs caution trespassers, but they read like empty threats. Some obviously did not heed the warnings and have left burned-out shells in their wake.

Throughout town, the roads show their age, and unruly brush closes in on some corners. Weeds burst through cracks in the pavement, the 50 kilometre-an-hour speed limit signs are faded, stop signs are marred with graffiti, and buildings that once faithfully served church congregations are identifiable now only by the wooden crosses clinging tenuously to the façades.

The wildfire was just one more calamity that has befallen the town in recent years.Some residential bays on the edge of town have been razed by wildfire, which this summer forced the evacuation of about 350 residents for more than two months. Concrete foundations and twisted metal are all that remain.

The wildfire was just one more calamity that has befallen the town in recent years.

Nature is beginning to reclaim the town of Leaf Rapids, which rose seemingly overnight in the woods 50 years ago.

Unless there is significant intervention by government or a private entity — and soon — it is at risk of being swallowed up by the land, its once-promising future eroded by time, economic misfortune and neglect.

It wasn’t always like this.

Fifty years ago, life in Leaf Rapids was a whirlwind.

There were freshly paved roads, construction on every corner and an influx of hundreds of miners and their families following Sherritt Gordon Mines’ discovery of vast copper and zinc deposits by nearby Ruttan Lake.

It was a heady place to be, and accolades soon followed.

The town, built almost in its entirety over just four years, received the Vincent Massey Award for Urban Excellence in 1975.

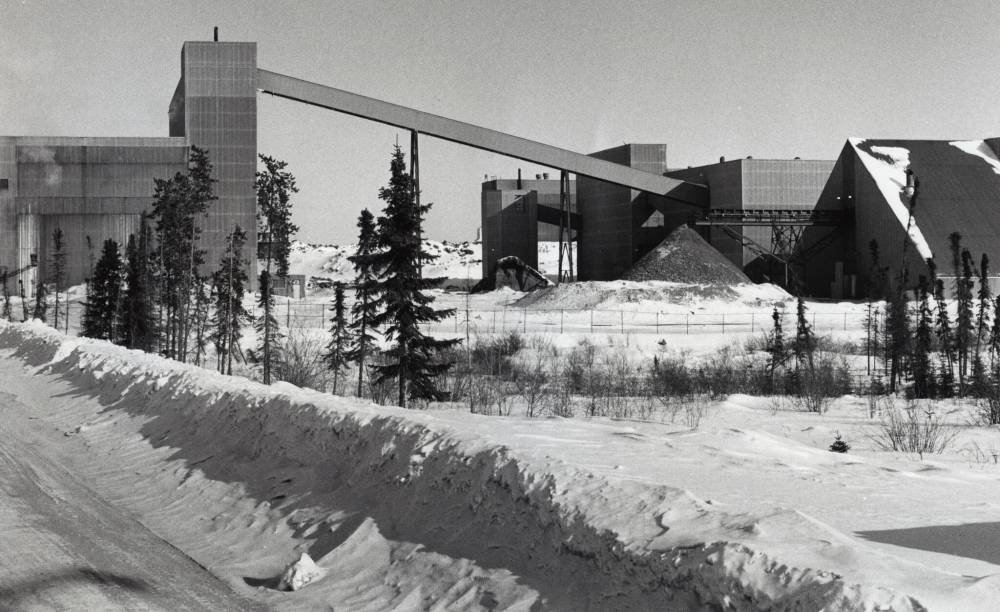

FREE PRESS FILES The town of Leaf Rapids in 1979. When it was built over a period of four years in the 1970s, Leaf Rapids was full of amenities.

The following year, the federal government selected Leaf Rapids as a model town to show delegates attending the United Nations Habitat conference in Vancouver. They came to visit from all over the world and marvelled at the “instant town.”

It was going to be the province’s northern crown jewel.

Typically, during this era, corporations were responsible for housing and services for their workers. The result was often a slapped-together shanty town. The company, not residents, ran the community and made decisions about infrastructure and amenities.

But Leaf Rapids was different from Day 1.

In late 1969, the mining company approached the province about needing to build a town to house its workers for the Ruttan Mine, which would have an operational lifespan of about 27 years and employ around 500 people.

The timing was perfect.

The then-Ed Schreyer NDP government was big on pursuing economic development in the north through its Northern Strategy, which aimed to provide opportunities for businesses and residents and bridge the gap between the sparsely populated region and the more cosmopolitan south.

FREE PRESS FILES Sherritt Gordon president Dave Thomas (second from left) and then-premier Ed Schreyer (third from left) officially open the town centre, an event that also signified the completion of the town’s build.

Following negotiations, the Schreyer government announced there would be a major departure from how mining towns were typically built.

The province, through the creation of a Crown corporation, would be at the helm of the townsite development, and the mining company would be placed on the tax rolls of the new community. This way the company contributed significantly to the tax base but only had one vote in how that money was spent.

“Building the first non-company mining town at Leaf Rapids will bring closer the day when it will be we, and not the multinational corporations, who will control our economic destiny,” boasted Vic Schroeder, who would later serve as an NDP MLA for Rossmere.

The mining company was also onside.

FREE PRESS FILES

“My congratulations are tinged with envy,” Sherritt Gordon president David D. Thomas said in a December 1971 Free Press article in which he applauded the town’s new residents and its bright future, “as the opportunity to be a pioneer in such an attractive and well-planned town is rare.”

FREE PRESS FILES

The townsite was chosen based on its long-term economic viability. The province believed it had untapped tourism and recreation potential as well as the ability to service future mine developments given its location in a richly mineralized area.

As part of that vision, a 230-kilometre gravel highway connected the new townsite with Thompson, further serving as a gateway to the North.

In four short years, Leaf Rapids would be planned and built to completion to the tune of about $18 million. It had all the amenities more populous southern Manitoba communities would envy: a health centre that rivalled any Winnipeg hospital, a curling rink, 14-room school, baseball diamond, tennis court, golf course, soccer field and airport.

There was even a town mascot and a newspaper: Willy the Wolf was a furry fixture at community and school events, and the front pages of the Forum reported school principal resignations and the need for more housing to accommodate the population boom.

“The opportunity to be a pioneer in such an attractive and well-planned town is rare.”

The Town Centre, which Premier Schreyer opened in September 1974 during a glitzy ceremony that included a talent show, community barbecue and grand ball, had all the desired services: a grocery, post office, 392-seat theatre, library, liquor store, jeweller, drug store and bank. It was touted as a cultural exhibition hub that would host workshops, seminars and concerts.

The first residents — a family of four — moved into town in late 1971. By 1976, the town’s population had swelled to 2,067. Leaf Rapids was a booming success.

In the heart of the community, the Leaf Rapids Town Centre stands in striking contrast to the surrounding decrepit homes, many of which residents say should be condemned. Its brown metal roof looms over the concrete parking lot, which, most days, serves as a gathering place for residents and a playground for kids.

To enter the town’s 210,000-sq.-ft. central nervous system is to be blasted back to the past; the interior’s faded pine wood panels and charcoal-coloured floor tiles appear lifted from photos of its 1974 grand opening, an event that symbolized the town’s successful completion.

In one corner of the mall, a boil water advisory from 2013 — which remains in place today — is tacked to the community bulletin board. Darkened windows and shuttered blinds mark nearly a dozen vacant commercial spots along the centre’s long, dim hallway.

NICOLE BUFFIE / FREE PRESS

During an October visit to the town by the Free Press, Ervin Bighetty’s 6-foot-6 frame is towering over a cash register at the Co-op, the largest commercial tenant in the building. He scans a case of water, bread and some Coca-Cola products and fields a request for two packs of cigarettes. Grocery options are slim since residents returned from the wildfire evacuation just days earlier.

Bighetty promises there will be more selection in the coming weeks and wishes the customer well. Shoppers know him by name, and he them.

Bighetty made headlines when he was elected mayor in 2018 for being the youngest and only the second Indigenous mayor to lead the municipality. After his election, he was featured in HuffPost articles and sleek Maple Leaf Foods videos about his plans to change the town’s slipping fortunes.

“I’m gonna do something. I’m gonna do something for the town,” a 28-year-old Bighetty, lounging in the council chamber sporting sneakers, a backwards hat and tinted glasses, tells the camera before it fades. The Maple Leaf video was an advertisement for the Maple Leaf Centre for Food Security, a charitable offshoot of the Canadian corporate food giant that sponsored the community garden Bighetty helped build at an abandoned trailer park on the edge of town.

There is interest in reviving Leaf Rapids.Young and perhaps a bit naïve, Bighetty had a plan to get Leaf Rapids to stand on its own two feet again. Capitalizing on the garden project, which still serves the community today, the idea was to build a series of geodesic domes to grow food, so not only could the town be self-sufficient, but the initiative would create jobs and possibly generate a revenue stream.

Nobody listened, he says, and the idea fell flat.

These days, Bighetty, now 34, advocates for the town from his office at the Co-op, where he manages operations. His tenure as mayor was cut short in 2019 when the province dissolved the municipal council after two representatives were removed for not attending meetings, and a third resigned. As a result, the town was placed under third-party administration, hired and paid for by the province. It is the only Manitoba municipality operating under outside oversight.

Steps down the hall from the Co-op, third-party administrator Way to Go Consulting Inc. uses the municipal office as a satellite site for when administrators Dale Lyle and Ernie Epp are in town. Lyle and Epp are based in southern Manitoba and visit the municipality when needed.

It’s a tenuous arrangement. Residents complain it leaves them without a voice or representation. It also has largely left the community stagnant financially; its budget sits at a mere $1.6 million per year while the total value of taxable private property in Leaf Rapids is about $1.8 million.

Multiple requests to the province to interview the administrators were denied. Their contract stipulates they are not required to speak with the media.

In 2022, the town’s health centre closed after all the nurses had left. Today, there is just one nurse practitioner. Any meaningful medical care must be sought hundreds of kilometres away — in either Lynn Lake to the north or Thompson to the south.

Although the bank closed years ago, Bighetty cashes cheques at his till for a small fee.

“The whole ghost town thing, it’s gonna happen eventually if things don’t change.”

The town’s main economic base is commercial fishing — the Churchill River is just five kilometres away, along with an abundance of nearby lakes — but many guides went without work during the summer months while wildfires raged across the north, further eroding a fragile economy that had already driven many to leave the community.

The main form of communication between administrators and residents is through the town’s Facebook page, but in a community with no cellphone service, word spreads slowly, leaving people feeling left behind and out of the loop.

A bleak outlook pervades the ruggedly beautiful landscape.

“The whole ghost town thing, it’s gonna happen eventually if things don’t change,” Bighetty says. “And that’s what I’m afraid of, that’s what you’re trying to prevent, from this place disappearing.”

Rosalie Linklater is preparing to move from Leaf Rapids, albeit begrudgingly.

She moved to Leaf Rapids from the nearby O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation community of South Indian Lake at age 16 to finish high school. She left when she was 27, seeking a change of scenery, but ended up returning to start a family.

NICOLE BUFFIE / FREE PRESS

“I’ve always been comfortable here because I know everybody. If my kid was on the other side of town I’d get a call right away telling me where they were,” she says.

Parents are innately involved with one another because they’re connected by culture, location and struggle, she explains. But the ties that help bind the community are unravelling.

Her children left for Thompson as soon as they could. Linklater, now 37, is considering a move to the neighbouring community of Nelson House to be closer to them and for a job opportunity with the community’s child and family services branch.

“I’ve always been comfortable here because I know everybody.”

Jobs in Leaf Rapids are sparse. The grocery store and a retail department store are the only meaningful opportunities, but residents claim they are available to a select few.

Linklater briefly held a job at the post office, but her employment ended abruptly when the encroaching wildfire forced residents to flee. The blaze, which would go on to burn nearly 1,763 square kilometres of boreal forest, also nipped at the town’s edges, destroying several properties.

A wildfire encroached on the town in early July, forcing an evacuation.Despite those setbacks, Linklater isn’t quite ready to turn her back on Leaf Rapids. “I don’t want to leave,” she says.

The decision of whether to stay or leave crops up in conversations with other residents, too.

Taylor Vick, 50, lived in Thompson from infancy to Grade 12, then moved to Nanaimo, B.C. He visited Leaf Rapids on a whim 13 years ago while en route to Ontario and never left.

Vick, a tall, slender man with strawberry blond hair and beard scruff to match, was eating instant noodles left over from his evacuation rations and playing video games when a Free Press reporter knocked on his door — left wide open — to ask about the burned-out home next to his.

NICOLE BUFFIE / FREE PRESS

The house was charred more than two years ago, he says, and no one has bothered to clean it up. The grass has overgrown the driveway and all that remains are blackened wooden boards sticking out of the foundation like rotting teeth.

Vick is one of the few people who live in the 15 or so homes still standing on his street, but he likes it that way. It’s private and he’s largely left alone.

He’s also gainfully employed; he’s the town snow plow operator and works eight months of the year, most years.

“I’m pretty much retired already, so it’s a pretty good retirement gig,” he says. “Not too many people are gonna give me a Dodge 2500 Power Wagon with a snow plow on the front to drive around all winter long.”

Does Vick like living in Leaf Rapids? Not particularly, he says, but opportunities for fishing and hunting are abundant and he spends his free time in the wilderness with his friends.

However, he adds, he would consider leaving if he could get the same kind of job somewhere else.

Fifteen years after it was touted as a town of the future, cracks in Leaf Rapids’ sparkling veneer were beginning to show.

Financial records from 1989 for the Crown corporation still overseeing the Town Centre and the public safety building housing emergency services show the province was acutely aware that the “ongoing viability of the corporation depends significantly on the ongoing successful operation of the Ruttan Mine or an appropriate alternative.”

Hudson Bay Mining and Smelting had taken over from Sherritt Gordon two years earlier and, upon discovering additional mineral deposits, claimed the mine would operate well into the next century.

Even if the mine were to eventually close, the Crown overseeing Leaf Rapids’ infrastructure was optimistic it wouldn’t necessarily be a death knell for the town.

FREE PRESS FILES

Workers, however, were not as confident. The 1986 census pegged the town’s population at 1,950 residents. A decade later, the count had been whittled down to 1,504.

On Oct. 29, 2001, less than two years into that next century, Hudson Bay Mining and Smelting announced the Ruttan Mine would be shutting down the following summer, owing to dwindling supply and low market prices for the precious metals. The last mining crew clocked out on June 28, 2002.

“A number of alternatives are currently being reviewed by the Town of Leaf Rapids for the utilization of the mine and/or the utilization of available housing in the Town. The ongoing viability of the Corporation will depend on the outcome of the implementation of the alternatives currently being reviewed,” provincial financial statements from 2002 state.

Following the announcement of the mine’s closure, the province met with local representatives and business and promised to initiate a transition plan for the community.

In a news release at the time, then-Flin Flon MLA Gerrard Jennissen called the town an important centre in northern Manitoba and said carving out a path for its future was vital.

“The point is that we cannot and will not simply give up on Leaf Rapids,” Jennissen wrote.

An archival photo of the Ruttan Mine site. Six companies currently hold a mining claim to explore and extract minerals in the vicinity of Leaf Rapids.While the town was working to establish a new economic base, residents and business were leaving in droves. In 2002, the province took extraordinary measures to keep the Town Centre afloat by renegotiating commercial rents to a flat monthly rate. For tenants of the trailer court situated on provincially owned land, rent was forgiven by the Crown corporation, leaving residents only responsible for property taxes.

The following year, the province reported the Town Centre was no longer self-sufficient, despite “several efficiency initiatives.” The Crown corporation started drawing upon its financial reserves to maintain services.

As the situation became more dire, then-mayor Barbara Bloodworth sent out a global SOS, encouraging people to move to the remote community, boasting about its cheap and readily available real estate.

“The point is that we cannot and will not simply give up on Leaf Rapids.”

“You can move to Leaf Rapids and buy a home for, you know, $20,000 and take the rest of your money and put it in the bank,” she told the CBC at the time.

She was also dreaming big, suggesting the soon-to-be shuttered Ruttan Mine could be transformed into a large-scale marijuana grow operation that would supply medical pot to the federal government.

The town was given $1.25 million by the province to assist it through its worsening crisis.

Despite a glimmer of hope in the mid-aughts, when Fields — a subdivision of Canadian retailer Hudson’s Bay Company — announced it would be opening a department store in the Town Centre, and the town restaurant re-opened, balance sheets continued to drip red ink.

“Revenues have continued to drop since the closure of the Ruttan Mine in May 2002 and as a result the Corporation is undergoing severe cash flow problems. The Corporation is currently reviewing their financial position and the long-term plans for the Corporation.”

By 2006, there were just 539 residents in Leaf Rapids.

Utik Bay splits off from Mistik Road, the main thoroughfare, on the east side of Leaf Rapids. Of the street’s dozen homes, only half show signs of life. The rest — boarded up with rotting plywood, the roofs collapsed — are barely standing.

While her grandchildren play on an abandoned property next door, Beverly Baker is cleaning up her front yard and home just days after returning following the mandatory wildfire evacuation.

Furniture and mattresses riddled with the stench of mildew and rotten food litter the yard. Her home sustained water damage from a temporary sprinkler system that was installed on roofs as a fire suppression tool; the food in her fridge and freezer spoiled following a month-long Hydro power outage.

She, like most others in town, is a transplant from the nearby fly-in community of Granville Lake, some 70 kilometres west. In 2003, the community’s sewage system failed and flooded the streets with waste. The approximately 70 residents were ordered out and nearly all settled in Leaf Rapids.

NICOLE BUFFIE / FREE PRESS

At the time, many of Leaf Rapids’ homes had been abandoned by miners and their families and were left under the jurisdiction of the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. It was an opportunity for Granville Lake evacuees to stay and wait out the remediation of their community. They went back for a time, but in 2006 the sewage system failed again, scattering residents once more.

Baker says she won’t leave Leaf Rapids unless an opportunity arises that includes a job and stable housing, or a return to Granville Lake.

The province says it remediated Granville Lake, and soil samples from 2016 showed no signs of contaminants, but former residents remain wary of the uncertainty, and the infrastructure has fallen into disrepair. Only one man still lives there, they say.

“There’s a lot of despair in this community.”

“I’m staying here because it’s the closest thing to home,” Baker says. “This is where our livelihood is.”

Leaving would be hard for Baker. It’s where she teaches her grandchildren their traditional way of life, where they play and where they feel safe.

“I’ve just gotten used to it because it reminded me of home…,” she says, but adds, “there’s a lot of despair in this community. It’s a dying town.”

The Canadian landscape is dotted by similar stories of disappearing towns, victims of the cruel reality of boom-to-bust cycles.

However, academics argue there is political and public interest in reviving a single-industry town like Leaf Rapids.

Northern sovereignty, First Nations empowerment and critical mineral exploration are all buzzwords sprinkled throughout the current provincial NDP government agenda — and they could unlock a new future for Leaf Rapids.

NICOLE BUFFIE / FREE PRESS

However, because the mine’s closure left a near-unfillable gap in Leaf Rapids’ economic base and there is currently little economic opportunity outside Manitoba’s metropolitan areas, there must be significant government intervention to revive the town, says Allen Seager, a retired associate professor at Simon Fraser University, who specialized in labour history and coal mining.

“If First Nations invest in the town with backing from Ottawa, that could be the way forward for Leaf Rapids,” he says. “It’s a native town now, so that puts a new cast on it.

“Nowadays it’s very hard to just pull the plug. So, there must be some boffins there in (the Manitoba) government who are thinking about this, and hopefully the boffins in Ottawa can think about it as well.”

A government-led working group was formed in 2019 to study the town’s long-term future and there has been talk of turning it into an urban reserve, but discussions were put on hold for unspecified reasons earlier this year.

NICOLE BUFFIE / FREE PRESS

The town’s declaration as a First Nation community would make sense; all but a few residents identify as Indigenous. Bighetty advocated for the move after council was dissolved but was left out of the conversation because he’s not an elected official.

The notion of “home” is complicated in the north, where traditional roots run deep. Granville Lake residents identify as belonging to Pickerel Narrows Cree Nation, despite the community being located within nearby Mathias Colomb Cree Nation territory and under its mandate.

Bighetty, who came from Granville Lake as a child, has talked with representatives from Mathias Colomb about giving Pickerel Narrows ownership over Leaf Rapids.

“(The land) is our traditional territory, from Granville Lake to Leaf Rapids,” Bighetty says. “I see my people suffering without proper housing or food and no one is helping them … It’s the least they can do.”

Kevin McPike, Manitoba’s assistant deputy minister for municipal and northern relations, says there has been little appetite from Indigenous lobbyists like Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak or Mathias Colomb leadership to organize ownership of the land.

The town’s infrastructure must also meet certain standards before the federal government will accept it as a First Nation, McPike explained.

The working group consulted with residents about the option, but they are more concerned about how their needs will be met today than what the community could look like in the future.

“The focus is on stabilizing the community now and providing those supports when they’re needed,” McPike said.

The province has already determined that the town is in no shape to operate on its own and will not hold a general election there in October 2026 when the next round of Manitoba municipal elections is scheduled, despite repeated calls from residents over the years to reinstate local elected officials.

Without proper representation, residents can’t advocate for the community. But no one it seems, including Bighetty, has any interest in stepping up to the plate.

“It’s just a public ridicule,” he says. “So, whoever’s going to be in that council, they can see what I’ve gone through for the last seven years.

“No matter how much you do, people will still come and say you’re not doing enough.”

“No matter how much you do, people will still come and say you’re not doing enough.”

The province says the third-party administration is focused on maintaining basic municipal services heading into winter, but aging infrastructure like the Town Centre and the wastewater treatment plant are not due for any upgrades or renovations in the future. McPike said decisions about infrastructure will be considered as part of any long-term plans for the town.

Meanwhile, residents say about 200 homes in town are vacant and about 70 should be demolished.

With the promotion of critical mineral exploration and a massive revamp planned for the Port of Churchill on the provincial and federal government agendas, Leaf Rapids could again be a hub for companies and their employees, said Glen Simard, Manitoba’s minister for municipal and northern relations.

BRANDON SUN FILES

Six companies currently hold a mining claim to explore and extract minerals in the vicinity of Leaf Rapids, according to the province.

“It’s all part of our focus towards renewal in the north, and we need these communities like Leaf Rapids … to all be ready for what we see as the economic opportunity that’s coming towards them,” Simard says.

Promising words, but the stark reality in Leaf Rapids tells a different story.

Mine Road snakes eastward out of Leaf Rapids for about 23 kilometres before it arrives at a vast, open space carved out of thick foliage. A massive lagoon of ice-blue water appears mirage-like, surrounded by acres of clear-cut land.

There are no obvious signs that 34 million cubic metres of precious metals were once mined here, but a closer look reveals the rock outcroppings from mine waste that still outline the property. The dirt is criss-crossed with deep ruts left by the heavy equipment used to clean up the site.

PROVINCE OF MANITOBA

In 2012, the province spent $54 million to plug mineshafts and work areas with gravel and clay as part of its responsibility to remediate orphaned sites. The kilometre-deep open pit at Ruttan Mine was filled with acidic mine drainage and treated to protect the surrounding northern landscape from future contamination.

The massive steel buildings and mills, which at the mine’s end of life employed 330 men and women, had been previously demolished.

“We need these communities like Leaf Rapids … to all be ready for what we see as the economic opportunity that’s coming towards them.”

The 10 years of rehabilitative work erased nearly three decades of history. Only memories of the mine exist in faded photographs and the scars left behind on the land.

Does a similar fate await Leaf Rapids?

“That’s the thing about these mining towns,” Seager says. “When the companies left, the people left, and that was it.”

Leaf Rapids was once a town of the future. Today, it desperately clings to the present, its legacy already a distant past.

nicole.buffie@freepress.mb.ca

Nicole Buffie

Multimedia producer

Nicole Buffie is a reporter for the Free Press city desk. Born and bred in Winnipeg, Nicole graduated from Red River College’s Creative Communications program in 2020 and worked as a reporter throughout Manitoba before joining the Free Press newsroom as a multimedia producer in 2023. Read more about Nicole.

Every piece of reporting Nicole produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.