The route cause

Getting concert promoters to choose Winnipeg is an art — albeit a frustrating one

By: Jen Zoratti

Posted:

Last Modified:

By: Jen Zoratti

Posted:

Last Modified:

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Opinion

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/04/2018 (2835 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

My first concert was not in Winnipeg.

It was December 1999, and my favourite band at the time was the Offspring (I was 14). The band was on the road promoting 1998’s Americana, and when the Canadian tour dates were announced, I was devastated: Winnipeg was nowhere to be found. And so, my mom took me to Edmonton as an early Christmas present.

This wouldn’t be the first such pilgrimage for music. In June 2003, I roadtripped down the I-29 to see my new favourite band, Pearl Jam, at the Fargodome. Winnipeg had been skipped over. Again.

Two years later, I would see Pearl Jam again — but this time, it was from floor seats at the still-new MTS Centre (now Bell MTS Place). Winnipeg’s downtown arena wasn’t even a year old yet and, already, it was fulfilling my concert-going wishlist.

Still, not every music group makes it to Winnipeg. So-called “North American” tours that only include Toronto and Vancouver are commonplace. And some bands have never played here, ever.

“I can honestly share that the question, ‘Why doesn’t my favourite band come to Winnipeg?’ is the most commonly asked question,” says Kevin Donnelly, senior vice-president of venues and entertainment for True North Sports and Entertainment. And he’s the guy to ask; Donnelly and his team are behind the event calendar at Bell MTS Place, Investors Group Field and the Burton Cummings Theatre.

“I get it with frustrating regularity,” he says with a laugh. “My job has always been — and will always be — defined by not what you’ve done, but what you haven’t done yet.”

Donnelly’s white whale isn’t exactly a secret.

“I’ve been trying to get Bruce Springsteen to come to town for two decades,” he says.

“And we’ve had the routing. We’ve had the financial discussions. But this isn’t a box on a shelf. The performer is a human, surrounded by other humans who affect their decisions. Someone’s kid is graduating, or somebody’s competing in a horse-jumping competition that changes the dates of the tour and you’re not on the list for whatever reason.

“Springsteen is one we’ve been close to too many times to count, but still not able to secure it. The building has been available, we’ve met the financial model, all the checks in all the boxes and it still doesn’t land. But I sincerely believe they have an interest to come and perform.”

For music fans, the concert experience begins the moment the house lights go down. But for the people who get Winnipeg’s name on the backs of tour T-shirts, it’s a months-long process that requires no shortage of hard work, hustle and passion — not just for music, but for our town.

So, let’s try to answer the question that Donnelly and others routinely field. Here’s how your favourite bands come to Winnipeg — and the reasons why they don’t.

A tour is born

The formula for getting a band on the road is pretty much the same: the artist goes into the studio, they release an album, then they hit the road to support that album. The artist is surrounded by a team that includes a manager and an agent. It’s the agent’s job to work with promoters and venue managers to arrange tours and negotiate contracts for shows.

“Then it’s when, where and how much,” Donnelly says.

When an agent calls, part of Donnelly’s job is to sell Winnipeg. “But I have to give them the truth about what that band can do here, how much they can charge, how much they can earn, what the risks are, what the rewards might be,” he says. “If I sell them down the river, they’re never phoning back.”

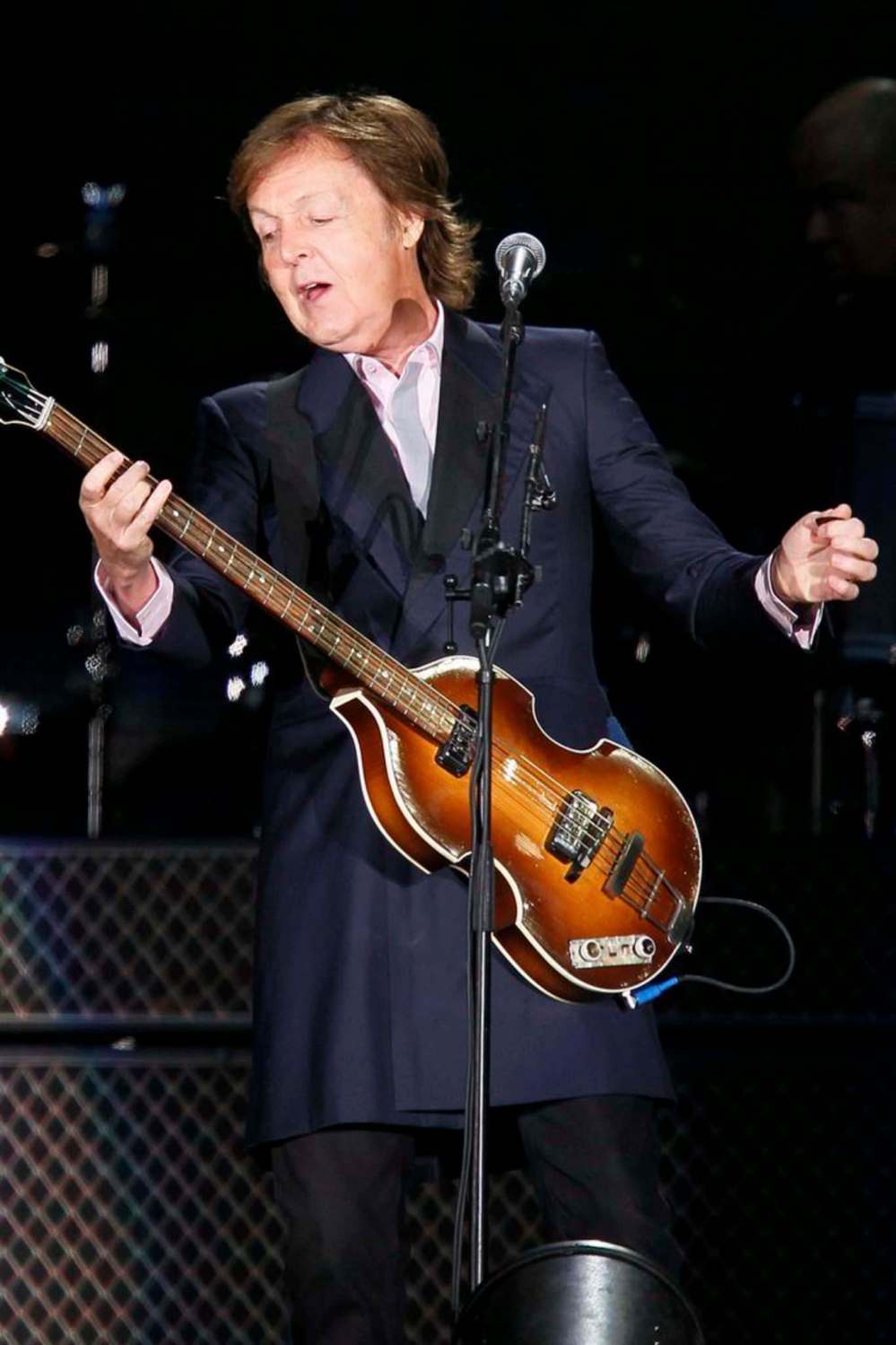

Agencies represent multiple acts. For example, the international agency Marshall Arts represents Cher, Pink, and Paul McCartney — three artists who have all graced True North-operated stages within the last five years. McCartney sold out Investors Group Field in August 2013; Pink sold out Bell MTS Place a few months later in January 2014.

“It’s that relationship, and delivering what you promise,” Donnelly says.

True North is relatively unique in that, as a sports team owner and a venue owner, it’s also willing to buy entertainment when a promoter isn’t willing to come to town.

“I’ll get a call that Band XYZ (is on tour). I’ll ask, does the promoter want to bring them to my town, and if the answer’s no, then I’ll ask why or why not, and if I still think that I see an opportunity where Winnipeg can deliver the requirements for that artist, we’ll pursue it and engage the band directly without an external promoter,” Donnelly says.“Springsteen is one we’ve been close to too many times to count, but still not able to secure it. The building has been available, we’ve met the financial model, all the checks in all the boxes and it still doesn’t land. But I sincerely believe they have an interest to come and perform.”–Kevin Donnelly

“So we become the promoter. True North does all the marketing, we take on the financial risk, we construct the entire business model and execution.”

In fact, it’s that kind of work that led True North to take over operations of the 1,600-seat Burton Cummings Theatre in 2014.

“(The Burt) would wait for someone to say, ‘Hey, we’ve got Great Big Sea, how much to rent?’” Donnelly says. “But when the phone doesn’t ring and we hear about a tour, we’re out there saying, ‘Hey, tell us how much because we believe Winnipeg will go crazy for your artist.’ We’ve been able to move that building from 30 nights a year to 90 nights a year.”

Relationships are key

Chris Frayer, artistic director of the Winnipeg Folk Festival, will often work with agents on building small tours for acts he wants to play the festival. “I built the tour for the Shins last year,” he says. “Similarly, I’m doing the same thing for Courtney Barnett this year.”

Relationships are also key on the festival circuit. Frayer partners with the 80/35 Music Festival in Des Moines, Iowa, and Basilica Block Party in Minneapolis — two other festivals that typically happen on the same weekend as the Winnipeg Folk Festival. “We often share bigger stuff with them: Brandi Carlile, the Shins, Ryan Adams, Head and the Heart,” he says, mentioning previous Folk Fest headliners.

The goal is to keep acts in the neighbourhood, so to speak. A band playing, say, the Pitchfork Music Festival in Chicago later in July may elect to tour out east.

For Kelly Berehulka, senior manager of entertainment at Casinos of Winnipeg, concert programming is a combination of being presented opportunities from artist agencies and using a little creativity to make those opportunities happen. “The ones that really make you feel good are the ones that you’re proactive and you find,” he says.

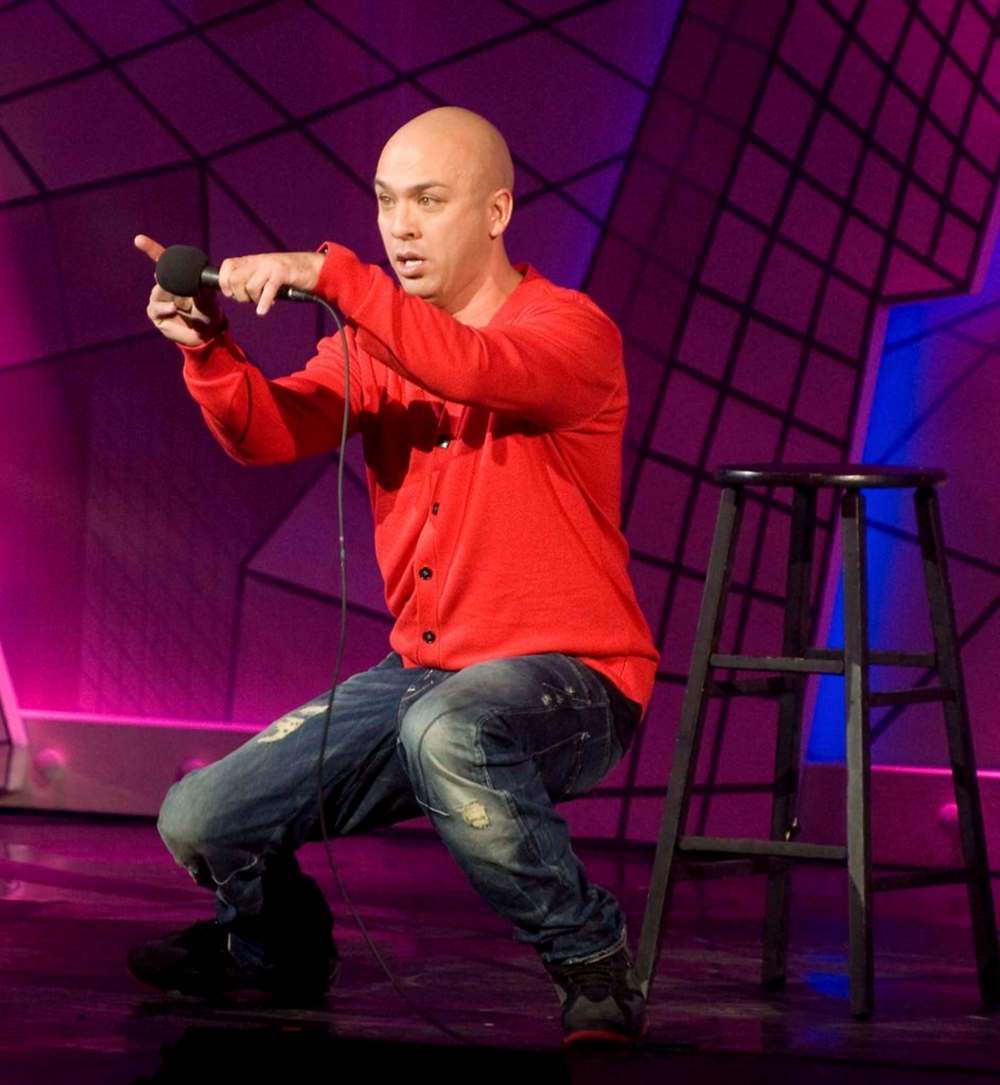

Take the Filipino-American comedian Jo Koy, for example. Berehulka saw his Netflix special, Jo Koy: Live from Seattle, called his agent, and booked a show for last December.

“It ended up being four nights,” Berehulka says. Not just four nights, but four sold-out nights, setting a new venue attendance record at Club Regent Event Centre.

Sometimes, however, months of effort doesn’t yield the desired result.

“I can put a lot of work in and not end up getting the band,” Frayer says. The War on Drugs and the National are two such groups that didn’t pan out for this year’s festival lineup. “But it’s definitely worth it.”

After all, just because someone is a no right now doesn’t mean they won’t be a yes in the future.

A complicated matrix

Assembling the event calendar at a venue such as Bell MTS Place requires precise organizational skills, but it also requires patience. So much patience. And sometimes it’s all about timing.

In a busy year, the arena will host 60 concerts. Donnelly has the Jets and the AHL’s Manitoba Moose to factor in as well. Of course, in an NHL arena, the Jets are priority No. 1. The general manager will ask Donnelly for 80 dates to send to the NHL head office to get 41 home games. And not just any 41 dates, either: Donnelly also has to consider the 41 best opportunities for the Jets to win — including the fewest back-to-back games and the least amount of travel.

Then, he’ll get a phone call from an agent.

“Somebody calls and says, ‘We’re planning a tour. We’re not sure if we’ll get to Winnipeg, but if we do, it’ll be Feb. 1 through 5. We’re just working out if it’s going to be two Chicagos, then it’ll be the 2nd. If it’s three Chicagos, it’ll be the 5th. So hold 1, hold 2, hold 3 just in case, but also hold the 5th.’ So, I’m holding 1 through 5 in any given week for one performer that may not come.”“It’s a very complicated matrix. The stars literally have to align for every tour.”–Kevin Donnelly

If more than one act is angling for the same window of time — it happens — and a better opportunity calls second or third, Donnelly has to call the first tour and ask if they’ve made any decisions and, in some cases, if he can get some of those held dates back.

“It’s a daily challenge,” he says. “An all-day, every-day challenge.”

Those decisions also affect an entire network of people. Let’s say a big-deal concert wanted Bell MTS Place on the 5th of the month, but there is a Jets game scheduled for that date already.

“I’d go back to the tour and say, ‘What are the chances of moving you from the 5th to 6th?’ and he says, ‘None, to say alive, you gotta be five.’ So I would go back to the team and say, ‘Can you go back to the league and see what we can do?’ Then, the league would have to go to the opposing team. It’s a domino effect that goes everywhere.”

And if, in this hypothetical example, Donnelly went back to the tour with an attractive proposal for the 6th, the agent would have to call the next city on the tour.

“It’s a very complicated matrix,” he says. “The stars literally have to align for every tour.”

A 40-date tour means 40 different business deals. Every detail has to be confirmed and committed to. If someone in the middle can’t make it happen, it can change the whole plan.

“The most disappointing one is when you’ve got a tour, you’ve had the discussion, you’re holding the date, you’ve kept your hockey teams away, and then you reach out and say, ‘Hey, we’ve done all this work, got everything in place, what’s the update on the tour?’ And they’ll go, ‘Life changed, I had to reschedule, you’re off,’” Donnelly says.

“When you do the work, and have the patience, and then you fall off and you’re not told why or give the chance to re-position yourself for consideration.”

Timing is also critical for events that happen during a fixed weekend such as the Winnipeg Folk Festival. “Most of the established bands who are coming this year, I’ve been waiting for a tour cycle to hit our window,” Frayer says.

And then it’s a matter of making sure that window includes Winnipeg.

A bump in the middle of the Prairies

Winnipeg is 2,660 kilometres from New York City. Winnipeg is 3,132 kilometres from Los Angeles.

“And when decisions get made exclusively in New York and L.A., it’s tough to stay on the radar,” Donnelly says.

It’s Winnipeg’s geographical location, not its population size, that can make it an unattractive tour stop. Unlike similar-sized American cities in the Great Lakes region, Winnipeg has no supporting markets of an equal size within an easy drive. Most touring acts — even the big ones — are road dogs, and Winnipeg is a 22-hour drive from Toronto and a 13-hour drive from Calgary.

“If I had Calgary or Minneapolis 200 miles away, it would be a different story,” Donnelly says.

What makes a city a “must-play” for a band has also changed. “A wise guy once said that there are four places a band needs to play: L.A., London, New York and the band’s hometown,” Donnelly says.

And then, outside of the obvious big cities, bands would play where they were popular. But thanks to the proliferation of streaming services, there are fewer pockets of regional success. A band that’s big in Dallas can be big in Seattle.

“Everyone can hear the same thing everywhere,” Donnelly says. “You’re not relying on your local FM station to introduce you to a song anymore.”

So then it becomes a matter of population density. “Someone might say, ‘If we’re No. 3 on the pop charts in every town we go to, then let’s go to the town with 4 million people instead of the town of 400,000.’”

On paper, it might seem like Winnipeg would be an obvious stop between, say, Minneapolis and Saskatoon. But then there’s the matter of artist and crew scheduling.

“There’s all these little nuances,” Frayer says. “Some artists only do a certain number of days in a row and need a day off; some need to go home to see their kids. People get exhausted. A lot of artists we deal with don’t fly, so they’re on the road. Agents and managers treat their artists like athletes.”

Of course, as Berehulka points out, Winnipeg is a major market for Canadian artists.

“If you’re a Canadian artist, you’re playing Winnipeg,” he says. “If you’re an American artist, then the venues are dealing with the American dollar. It’s more of a challenge to get them across the border. You have to work with other venues across Western Canada collectively putting in offers on a tour to make it more attractive to, say, Huey Lewis or Foreigner or whoever it might be. There are a lot of marquee U.S. groups who could make their entire living never crossing the border.”

Donnelly echoes that sentiment. “If you’re playing Minneapolis, Boise or Milwaukee suddenly looks more appealing than Winnipeg,” he says. “No border.”

The lousy loonie

Getting top-tier American acts across the 49th parallel for a concert can be difficult, especially when the Canadian dollar is only worth 78 cents in the U.S. Canada’s tax structure is also different. Winnipeg can be priced out.

“I’m routinely having to decline offers because I can’t meet that band’s financial demands,” Donnelly says.

The price of talent is also going up. “We’re not talking three per cent per year — we’re talking 40 per cent,” Donnelly says. In some cases, performers are offered what’s called a guarantee, which is a set fee they are guaranteed regardless of how the show sells. “We’re talking about the same artist guarantees going up 25 per cent in 12 months. And they’re doing it without having a hit.” Big guarantees are riskier for smaller markets.

All of these things will affect where an artist performs. The first leg of a North American tour generally includes roughly 25 “A-markets,” including Chicago, Toronto, Dallas and San Francisco.

“But while Leg 2 used to pick up Kansas City, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Saskatoon, and Boise, Leg 2 is now Chicago, Toronto, Dallas, San Francisco,” Donnelly says. “It’s going back to the same markets for a second time.”

The loonie also affects festival bookings. “We’re not charging 30 per cent more per ticket to make up for the lousy exchange rate,” Frayer says of the Winnipeg Folk Festival. “We’re increasing our budget, and keeping our ticket prices basically the same.”

But it’s not all bad news. “The American dollar has made it more challenging to bring American acts, but what it’s also done is increased how many Canadian acts we’re programming,” Berehulka says, pointing to April Wine’s May 25 show at Club Regent Event Centre, which sold out in three days.

“It gets to the point where we’re just not able to play ball with some of the acts, but that’s fine,” Berehulka says. “It opens up a spot for someone else.”

“Hey, why don’t you get…”

Most music fans have a list of artists they’d like to see come to Winnipeg, and many of them are not shy about sharing it with the people who make those kinds of decisions.

But geography and the exchange rate aren’t the only challenges programmers face. It’s a music-industry maxim that an artist must tour to make a living. That’s mostly true — unless you’re a hip-hop artist.

“The hip-hop market, they drop a record and it’s a big record before they hit the road,” Donnelly says. “So, they only do 25 dates and there’s no second leg. The record is selling.

“Being the No. 1 listened-to genre on the planet, it’s the least touring genre out there. Then the frenzy’s on. Everybody wants Kendrick (Lamar). Everybody wants Drake. Everybody wants Jay-Z. It’s a seller’s market. They get to pick.”

Russ, an Atlanta-based hip-hop artist, is performing at Bell MTS Place on May 25 — the sole hip-hop date on the books so far for 2018 at the downtown arena.

Over at the Winnipeg Folk Festival, Frayer will often get emails from fans suggesting potential mainstage headliners. But he has to consider what makes sense for the festival, on a practical, financial and logistical level.

Frayer says he tends to stay in the Burt/Centennial Concert Hall range — that means focusing on acts such as Lucinda Williams or Wilco. Folk Fest’s focus, Frayer says, is on community and discovery. (Not that the Winnipeg Folk Festival hasn’t had big-name headliners; when Elvis Costello played in 2009, he was the first to perform on Wednesday night, ushering in a five-day format the festival kept until 2015.)

“We still want Winnipeg Folk Festival to be the headliner,” Frayer says. “When we get suggestions about really big bands to book, like Mumford and Sons, or the Lumineers or Arcade Fire, I think what people forget is that not only are those bands hugely expensive — like, my entire budget for some of them — but then all of a sudden it’s, ‘Are you going to the Mumford and Sons show at Birds Hill Park.’ “

Besides, the festival doesn’t have the infrastructure to support a show that can also play an arena.

“I look to someone like Kevin and True North to bring in those shows,” Frayer says. “The Lumineers finally came to MTS Centre (in 2017) and everyone was happy.”

Fans are No. 1

Connecting an artist with their fans — especially fans who have never seen their favourite band live before, or haven’t seen it in 20 years — is what it’s all about. If artists and fans alike leave a concert feeling great, “that helps the entire city,” Berehulka says.

Sometimes making a show happen requires some above and beyond effort, such as driving down to down to Grand Forks to physically retrieve an artist, as Frayer had to do in 2015, when Alex Ebert, the lead singer of Thursday night headliner Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros, lost his passport. “I’ll do anything for our audience,” Frayer says.

The concert-going landscape is also different than it was 15 or 20 years ago. The advent of Bell MTS Place and, later, Investors Group Field meant more opportunities to book bands that previously wouldn’t have played Winnipeg. The Burt is busier than it’s been in years. Smaller venues, such as the Park Theatre and the West End Cultural Centre, also boast full calendars. Casinos used to be the domain of tribute bands and heritage acts; they’ve beome a viable destination for all kinds of artists.

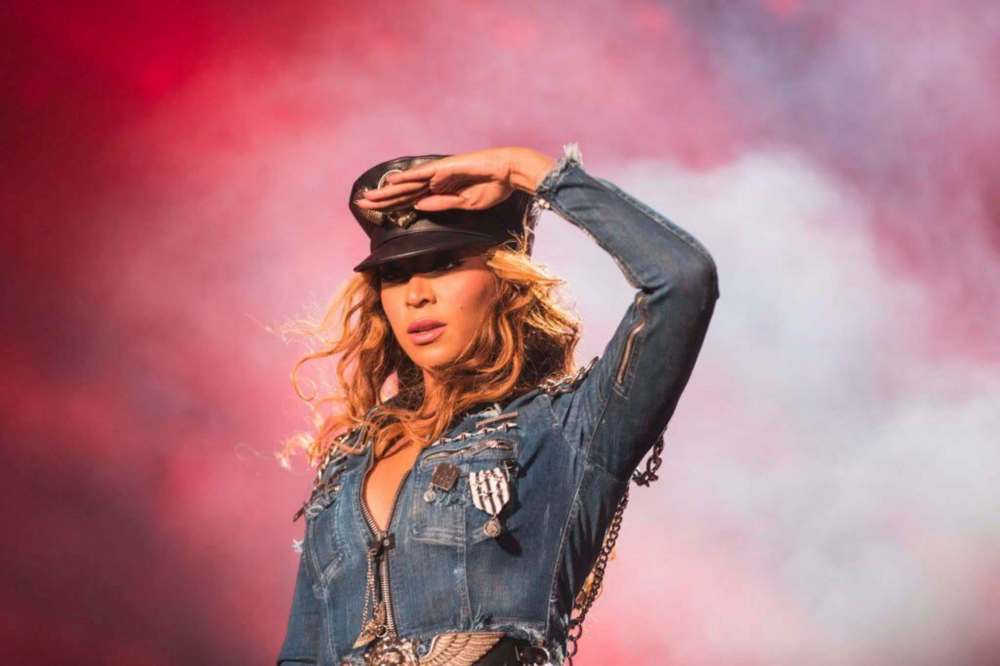

And when Beyoncé and Jay-Z performed at Investors Group Field in 2014, Winnipeg was one of just two Canadian dates on their On the Run tour.“The live music we get right now is insane. You have a higher probability of seeing your favourite band now, obscure or not.”–Chris Frayer

There are more recent wins, too. Berehulka was still buzzing from the weekend when I connected with him. “We had Randy Bachman Friday and Saturday, so after the Randy Bachman show, I’m driving from Club Regent back home to St. James, driving through downtown past the concert hall where John Cleese was letting out, past Bell MTS Place where the Moose were letting out, past the Burt, where Johnny Reid was letting out,” he says.

“In one night, all that was happening. It was cool to see the city energized, and the winner here is the Winnipeg entertainment customer.”

“Teenage me, 20-year-old me would have loved right now,” Frayer says. “The live music we get right now is insane. You have a higher probability of seeing your favourite band now, obscure or not.”

And if not now, there’s always the possibility of the future.

“Every get is important,” Donnelly says. “We might not always get it, but we’re always, always trying.”

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a columnist and feature writer working in the Arts & Life department, as well as the author of the weekly newsletter NEXT. A National Newspaper Award finalist for arts and entertainment writing, Jen is a graduate of the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech and was a music writer before joining the Free Press in 2013. Read more about Jen.

Every piece of reporting Jen produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.