Location, location, location

Art exhibition explores Canadian cities' chameleonic ability to fill in for world metropolises on film

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 31/05/2021 (1645 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Maybe you’ve seen the 2005 film Capote, in which the story moves from glamorous cocktail parties in Manhattan to a terrible crime at a windswept Kansas farmhouse.

The project was filmed in Manitoba, with the Fort Garry Hotel, the Manitoba Legislative Building and Stony Mountain Penitentiary standing in for locations in mid-century America.

That kind of strange cinematic magic is at the core of Impostor Cities, Canada’s official representation at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale. The multimedia installation project explores the ways Canada’s structures and cities double as other places in movies and TV.

Canada is the third most filmed country in the world, after the U.S. and Britain, but it rarely represents itself, instead offering itself up as a flexible, adaptable cinematic doppelganger.

Curated by former Manitoban David Theodore, an associate professor of architecture at McGill University, and the Montreal-based architect Thomas Balaban, Impostor Cities takes a serious but playful look at our Hollywood North status.

What do the chameleon qualities of our landscapes suggest about Canadian identity and Canadian architecture? What happens when real cities transform into fictional cities, through the mysterious alchemy of film, and what does that say about our digital age, as we increasingly experience the world through screens?

According to the curatorial statement: “Canada’s architecture is film-famous, but unlike Paris, New York, Lond on, or Rio de Janeiro, our cities rarely play themselves in film and television. Toronto stands in for Tokyo, for example, while Vancouver and Montreal masquerade as Moscow, Paris, and New York.

“From our streets to your screens, Canada provides the architecture for the ctional worlds we all love. Canada’s cities frame the action heroes of X-Men and Pacic Rim, the dramas of The Handmaid’s Tale and Brokeback Mountain, and even the cosmic exodus in Battlestar Galactica.”

”Canada’s architecture is film-famous, but unlike Paris, New York, Lond on, or Rio de Janeiro, our cities rarely play themselves in film and television.”

As Theodore explains in a recent Zoom call with the Free Press: “One of the settings we had in our mind is when you’re on an airplane and you see five or six films on the back of seats of the airplane at once, and you could be sitting there and seeing four or five different Canadian cities without realizing it, because you’re watching Hollywood films.”

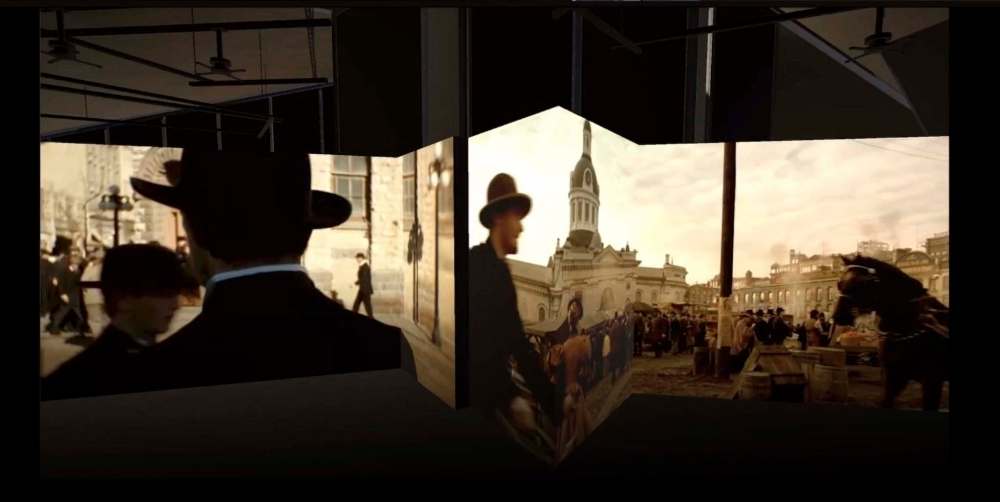

In the on-site installation of Impostor Cities in Venice — which opened on May 22 and will run until Nov. 21 — the Canadian Pavilion has been wrapped in green fabric. Green-screen technology and a smartphone app then conjure up visual images of iconic Canadian structures and cityscapes used in film and TV.

Inside the pavilion, the Screening Room features an immersive four-channel video installation playing clips of more than 3,000 movies and TV shows shot in Canada. In the Library area, viewers can take in interviews with Canadian filmmakers, critics, scholars and writers, including Guy Maddin, David Cronenberg, Elle-MaijaTailfeathers, Mary Harron, Douglas Coupland and Sarah Polley.

The aim, according to Thedore, is to “put people into ‘movie mode,’ which is about attuning you to the way you might experience architecture through watching something onscreen.”

There is also a significant online component to the project — which can be viewed at impostorcities.com — crucial at a time when international travel is so difficult.

(Thedore himself is currently in code-red lockdown in Montreal.) The website features multiple windows in which talking-head interviews alternate with cinematic supercuts, all connected by an evocative soundscape. Even though the project was conceived before the pandemic, its emphasis on screen images means it has been able to adapt, in some ways, to COVID restrictions, and even become accessible to a larger audience.

With our legacy of British influence, our proximity to the United States (“the elephant to the south,” as Theodore calls it), and our wealth of international-style modernist structures, Canada seems to have a lot of buildings “that look familiar but aren’t so recognizable that people will see them and say, ‘Wait a minute…’”

“David Cronenberg suggests that Canadian cities are great because they are really good actors,” Theodore relates. “They change. They’re good at imitating other places, and that’s a positive thing.”

Take the campus of the University of British Columbia. “UBC is the ninth most popular filming location in the world,” Theodore says, partly because its buildings range from Tudor-style traditional to space-age modern, allowing film crews to create the worlds of Smallville or Josie and the Pussycats or Tomorrowland.

Sometimes there are hilarious cracks in the illusion. Theodore cites Jackie Chan’s Rumble in the Bronx, in which Vancouver’s North Shore mountains are clearly visible in the background. But often the movie locale ends up defining how we see certain aspects of our world.

“We have a sequence of 10 to 15 films all filmed at the Lakeview Restaurant, a late-night diner (in Toronto), and that’s what a diner looks like now in movies,” explains Theodore. “If you’ve gone to movies in the last 20 years, you think that’s what a diner looks like because that’s where they film.”

So, what does Winnipeg represent on film? “Winnipeg’s hallmark is Hallmark films these days,” suggests Theodore, speaking of the many Christmas movies that get lensed here, but he also references period dramas such as Capote and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford.

And while the look of the buildings and streets is important, you also need to back it up. “Certain places know how to promote themselves as filming locations,” says Theodore.

“There’s nothing better than proud Winnipeggers trying to identify locations in a film.”–Kenny Boyce

That’s where Kenny Boyce comes in. Manager of film and special events at the City of Winnipeg, Boyce is one of the interview subjects in Impostor Cities.

In a phone interview with the Free Press, Boyce explains why Manitoba attracts film projects.

“They come here for great crews, amazing locations, a very lucrative tax credit and the easy ability to get in and out of neighbourhoods where they can tell their stories,” Boyce says. “In the Sean Penn film Flag Day, we had 10 locations in one day, which is incredibly hard.”

According to Boyce, Manitoba often doubles for the American Midwest, but we’ve also played San Francisco, New York and more. “When we go outside Winnipeg, with Lake Winnipeg, it’s sandy on one side, rocky on the other, so we can play oceans,” he says. “We have a desert.”

And film crews can move not just through space but through time: “We’re lucky to have intact neighbourhoods from all different decades,” notes Boyce. “There are still great areas of the city where you can look down the streets and it looks like the 1930s, ‘40s or ‘50s.”

Of course, what we end up seeing at the multiplex is Winnipeg but also not Winnipeg. “There’s nothing better than proud Winnipeggers trying to identify locations in a film,” Boyce says. “Winnipeggers love to look at their town, but it can be psychologically confusing to us when a character walks out of the Millennium Library and suddenly they’re beside The Bay or in Osborne Village.”

What we see on the screen is our city but also somewhere else, a city that only exists through the movies.

According to the project’s curatorial statement: “Impostor Cities brings us together in a shared cityscape. It is a place that most people have not visited physically, but that exists in the mindscape of nearly every global citizen, constructed through multiple impressions of Canada’s architecture and landscapes” conveyed through film and TV screens.

That’s something to consider the next time you’re scrolling through Netflix: that shining 24th-century metropolis, that zombie-infested wasteland, that spooky abandoned mental hospital, that folksy slice of small-town Americana might be closer than you think.

As Theodore suggests, “You know a lot about Canada through your screens that you don’t know you know.”

alison.gillmor@freepress.mb.ca

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.