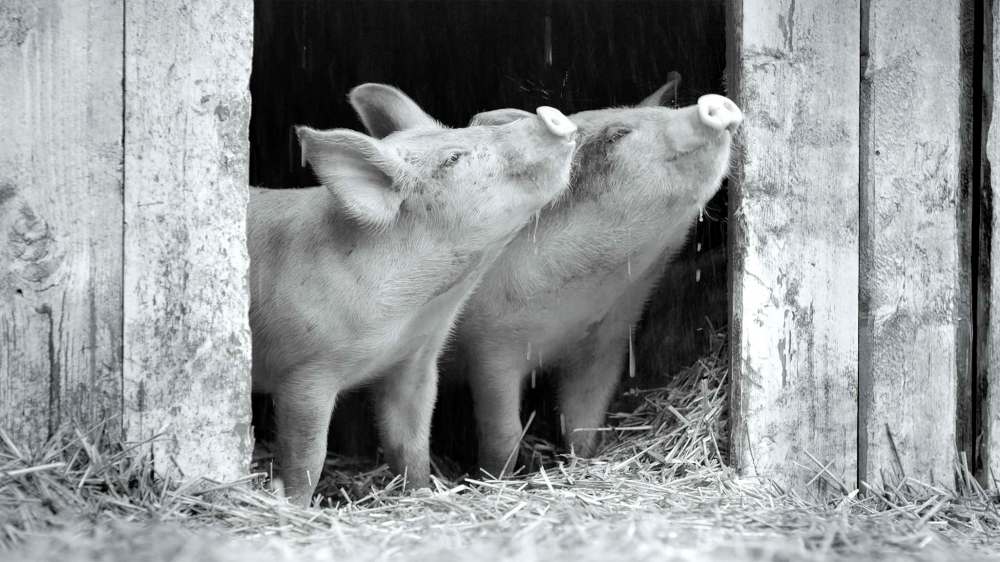

Fine swine

Pair of pig-related films herald return to Cinematheque theatre

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/08/2021 (1547 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

After a pandemic period of online-only programming, Cinematheque welcomes film fans back to the theatre this weekend with a revelatory pair of pig-centred films.

While Pig and Gunda are different in tone, effect and levels of onscreen pigginess, both films in this porcine double bill ask us to consider the connections between humans and other animals.

In the wonderfully, wilfully odd drama Pig, Nic Cage stars as Rob, who lives in an isolated cabin amid the grey-green beauty of the Pacific Northwest. Rob’s only companion is his snub-nosed truffle pig, who shares his supper and bunks down next to his bed when he goes to sleep.

Rob gets a simple subsistence living from his pig’s foraging, while Amir (Alex Wolff from Old), who arrives once a week to collect the precious subterranean fungi and sell them on to hipster Portland restaurants, gets a yellow Camaro and a Gucci belt.

When Rob’s pig is stolen in a violent midnight raid, all he cares about is getting her back. He heads into the city, with a reluctant Amir as his driver.

The presence of Cage, who these days is often seen screaming his way through direct-to-video cheapies, might make you think you’re in for a roaring rampage of revenge.

But in Pig the conflict is mostly interior. Cage is underacting for a change, his mostly silent and soulful presence reminding us of what made him great.

While there are bursts of violence — Rob has blood on his face for almost the entire film — the low-key story, scripted by Vanessa Block and Michael Sarnoski, who also makes a strong feature-film directorial debut, is often philosophical and frequently funny.

As the characters journey through the Portland food scene, outré fairy-tale elements combine with sharp-edged political allegory to hold up a very dark mirror to late-stage capitalism.

There’s a bizarre, baroque underworld fight club for restaurant employees. There’s a scathing satire on the fetishization of foodie “authenticity.” (A server at an exclusive new resto solemnly promises spiritual enlightenment via “emulsified locally sourced scallops encased in a flash-frozen seawater-roe blend on a bed of foraged huckleberry foam bathed in the smoke of Douglas fir cones.”)

Pig is about what we value — arbitrary economic value versus meaningful human value — all mediated through money, power and food.

Eventually, it’s revealed that Rob was once a hot Portland chef, before some unspecified loss — which has to do with a woman’s voice that he listens to on an old cassette player — drove him into the wilderness. One weird blank spot in an otherwise thoughtful film: The men are completely defined by their relationships to women, but these women are all absent.

As the title suggests, the story is also very much about a pig — when Rob is asked, repeatedly, what he wants, he says he just wants his pig back — but that pig, after a brief indelible intro, is mostly absent.

● ● ●

In Gunda, on the other hand, the pigs are present — completely present — in a way that is rarely explored on film.

In this extraordinary experimental documentary, Russian filmmaker Viktor Kossakovsky (Aquarela) follows a mother pig and her piglets as they eat, sleep, wander and squabble. There are no people, no music, no narration, just a deep, quiet focus on domesticated animals going about their daily lives.

The film is entrancingly beautiful, shot in richly textured, high-resolution black and white, often with hypnotic close-up detail. The ambient sound includes birdsong, the buzz of insects, sometimes the muted noise of distant machines.

Gunda makes a convincing argument for the in-theatre experience, and not just because its technical achievements benefit from a bigger screen and better audio. At-home online viewing can be prone to distractions and interruptions, and the film’s pacing, its slowness and closeness, call out for the immersive, intimate experience of sitting in the enclosed dark.

This is a film that demands not just concentrated looking but a kind of cinematic surrender. You don’t just watch Gunda; you give yourself over to it.

There are chickens — including an exuberant one-legged fowl — who arrive packed in a cage and then tentatively explore the freedom of their new yard. We also see a herd of cattle, let out of a barn and kicking up their heels. Tormented by flies, the cows stand in pairs, nose to tail, so they can swish each other’s faces.

Mostly, though, the film follows the titular Gunda, the mother pig, and her babies. We see the birth of the piglets, still slippery and struggling to suckle, and then watch as they grow, trailing after their mother as they explore.

The piglets are appealing, of course, but this is not a cute animal film. Kossakovsky never anthropomorphizes these pigs and cows and chickens. He takes them on their own terms, literally getting down to their level to see the world as they see it.

While we often seem to be mere centimetres away, there are several shots where the animals are at some distance, staring directly at us. They seem to be encountering the cameraperson — and by extension us — as we are encountering them, as fellow creatures, different but connected.

Kossakovsky’s exploration of this connection is rigorously unsentimental. (While the chicken footage comes from an animal sanctuary, the pig sequences come from working farm, where there is birth but also death.) But the cumulative emotional effect is overpowering, particularly in the film’s rending closing moments.

An extraordinary expression of pure cinema, Gunda is, in its own potent and poetic way, also a message movie, making an eloquent plea for the humane treatment of animals, without a single word spoken.

alison.gillmor@freepress.mb.ca

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.