Bonded by yaleburgers and shoestring fries C. Kelekis ‘counter’ culture built a lasting legacy in the city it reflected so well

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/02/2023 (1026 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The most famous french fry in Winnipeg was made by a Greek man who came from Turkey.

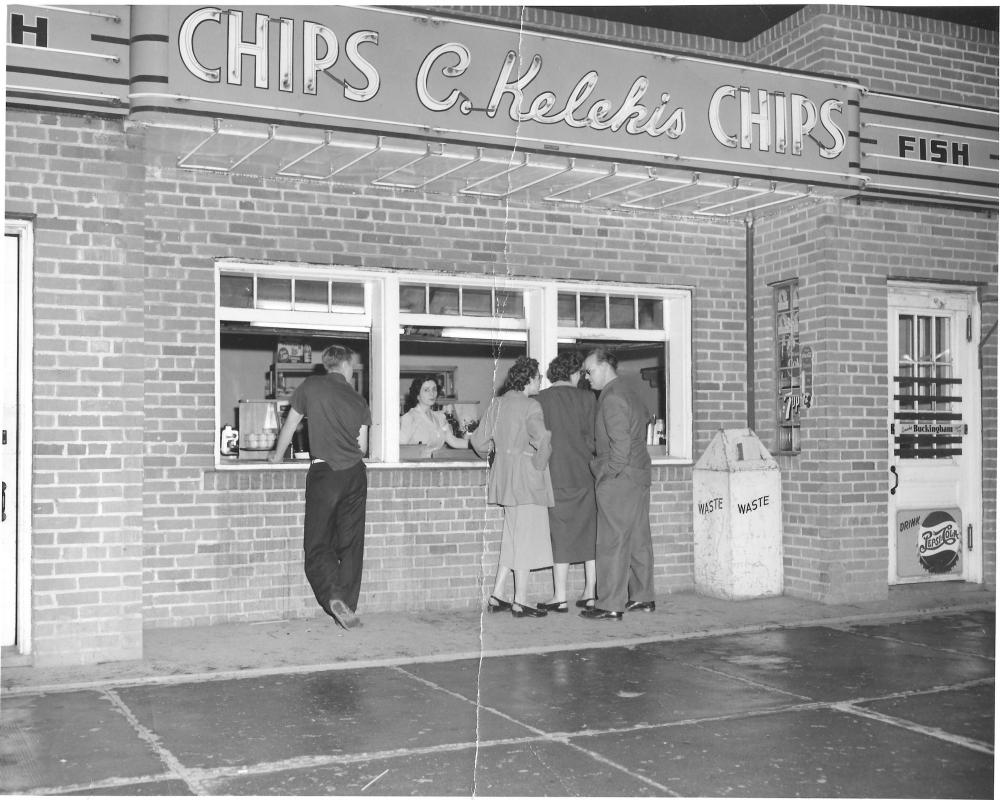

He cut the chips thin, like shoelaces. At first, he sold them from the back of a Model T, which he ferried around the city throughout the 1930s, parking the automobile along the sidewalk and waiting for the hungry to hand him a few nickels in exchange for starchy strings of spud.

He wore an ivy cap and a thick black moustache, a white jacket and a necktie. As much as Chrystomis Kelekis was a gourmet, he was, first and foremost, a businessman. If he was to deep-fry potatoes and sell them to the city as fine-dining, he knew he had to look the part of a distinguished gentleman. Deep down, he viewed finger-food as the great equalizer: every customer, whether rich or poor, looked the same with a splatter of ketchup on his lapel and a pour of hot coffee in his mug.

In due time, the name Kelekis would become inseparable from Winnipeg’s North End: The family restaurant was for 70 years a landmark near the corner of Redwood Avenue and Main Street. It served snappy wieners to prime ministers and to Winnipeg Jets, to Ukrainians and to Poles and to Germans and to Jews. It brought South Enders north and kept North Enders where they were raised. It served millions of pounds of potatoes, sliced into delicate laces and fried until golden in fatty lard.

For former customers, it will be difficult to believe it has been 10 years since the last plate of shoestring fries was served.

When C. Kelekis closed down, in January 2013, it was mourned as if the restaurant — with its orange countertops, walls of photographs, salty smell, and never-ending chatter — had been a living entity.

But it takes much more time to build a legacy than it does to peel a potato.

When he emigrated to Winnipeg in 1918, with his wife Magdelene, Chrys Kelekis was 30 years old, soon to be the patriarch of a family of eight. The descendant of silk merchants, he left Turkey in 1913 to escape persecution by the Ottoman army, who before the First World War targeted Greek residents with massacres and mass expulsions during what is now known as the Greek Genocide.

They first went to Montreal, and then to Edmonton. An asthmatic, Kelekis and his wife settled in Winnipeg for its cold, crisp air.

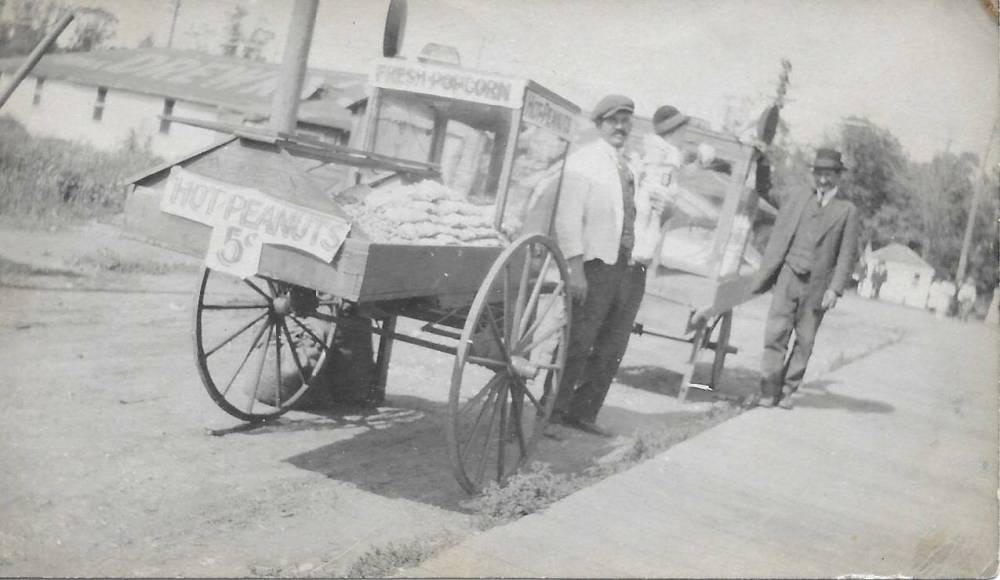

Arriving in a new city, with very little command of the English language, one thing Kelekis did possess was an impetus to earn money independently. Another thing he had procured was a wagon, which he promptly filled with hot peanuts and a mobile popcorn popper. Long before he had a motorized vehicle, and well before he and his family would perfect their famous french fries, Kelekis would pull his cart from the family home on Maryland Street to the old Osborne Stadium — now the site of the Canada Life offices — where the Winnipeg Blue Bombers played their home games.

SUPPLIED Chrystomis Kelekis with his peanut and popcorn wagon.

For five cents a bag, Kelekis sold the roasted legumes and aerated kernels to the besuited and to the besotted, both before and after the match was over.

“A lot of people don’t realize it started with popcorn and peanuts,” says Barb Hall, a retired Winnipeg schoolteacher and one of Chrys Kelekis’s granddaughters.

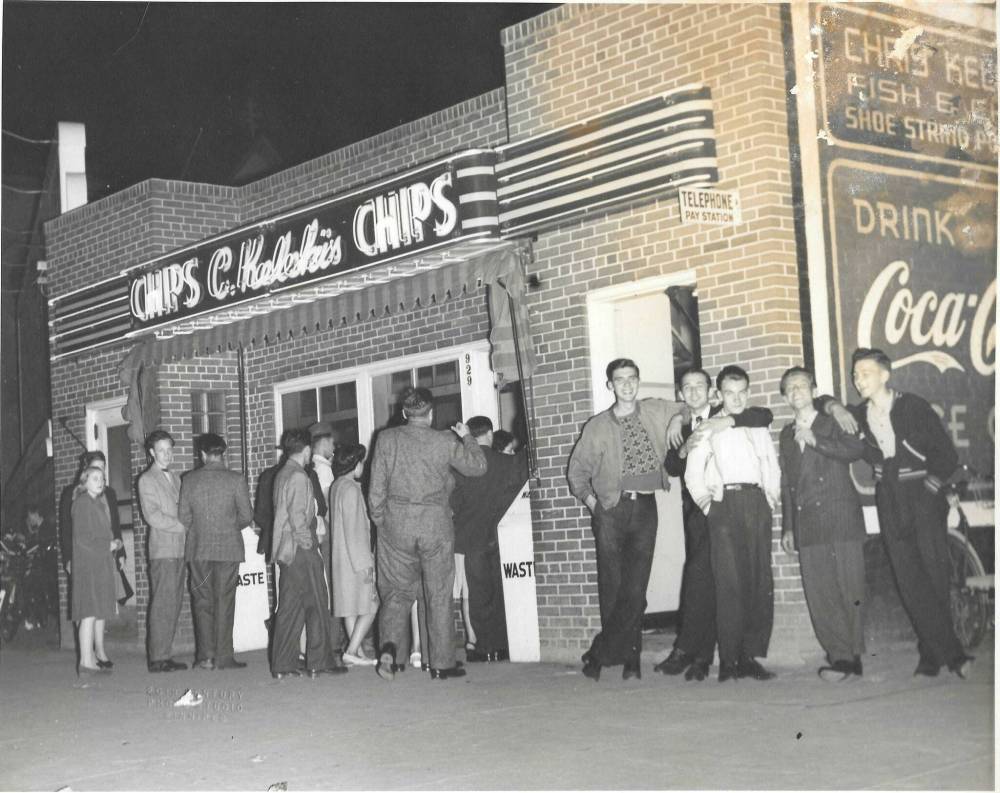

As his children — Evelyn, Sophie, Chryse, Isabel, Fotina, Mary, Becky and Leo — grew up, the Kelekis name was affixed to brick and mortar, first at 929 Main St., and later, at its iconic location near the corner of Redwood and Main. The kids learned the trade, and how to use its tools — the potato peeler, the chipper, the fryer, the cash register — by watching.

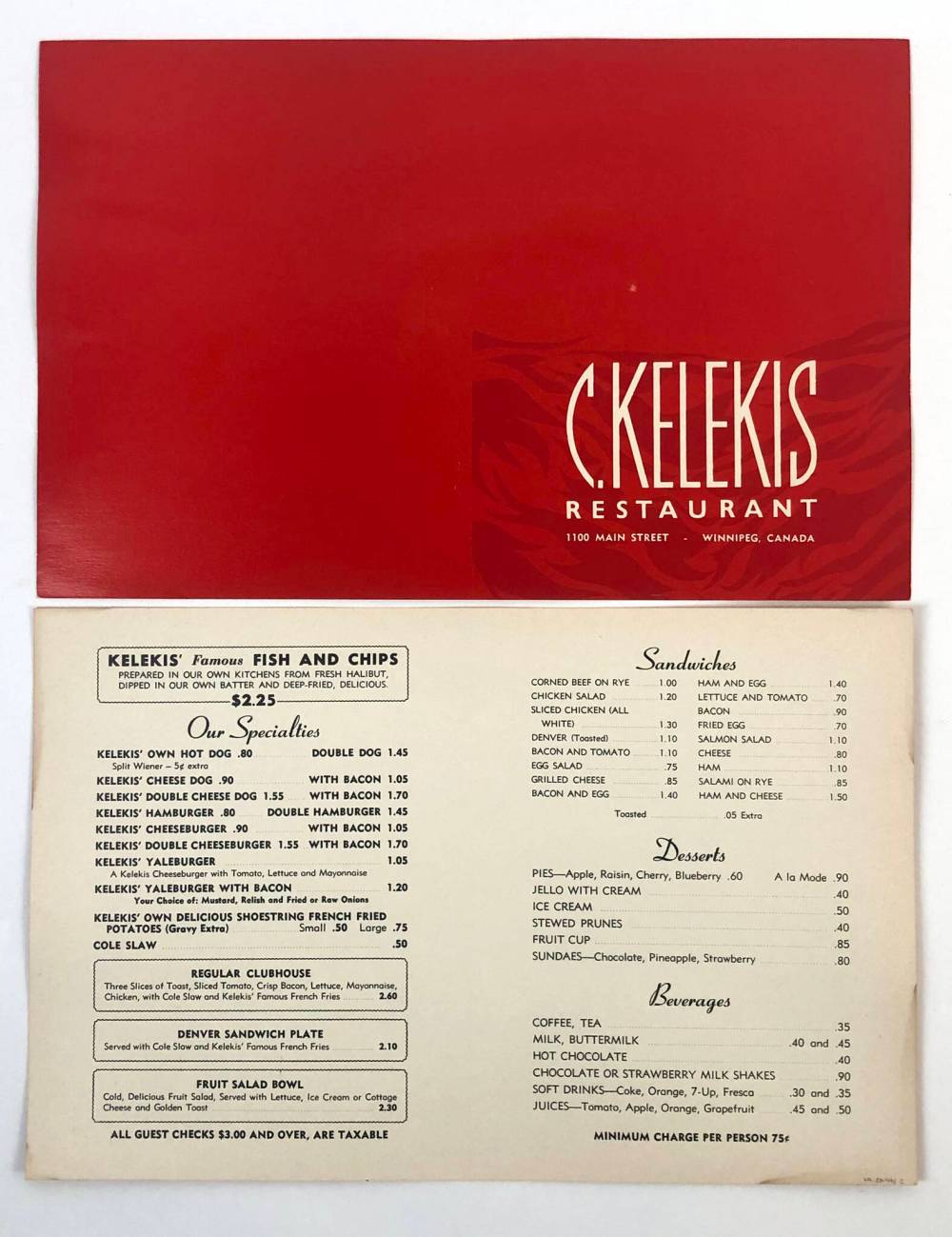

In the 1950s, wearing leather jackets, long skirts, blue jeans and tailored suits, customers stood on the sidewalk at the takeout window, waiting for menu items like Manitoba Sausage double dogs ($1.45), salmon salad sandwiches ($1.10), stewed prunes (40 cents), and Yaleburgers ($1.05). That last sandwich, says Barb Hall, was named after a customer named Yale Lerner. “For some reason he wanted his burger with lettuce and tomato,” she says. “Someone said, ‘We should put it on the menu and name it after you.’” So they did. The version that made the cut had tomato, lettuce, and mayonnaise, as well as a slice of cheese.

SUPPLIED Customer line up outside C. Kelekis’s first brick-and-mortar location on Main Street near Selkirk Avenue.

If not quite a melting pot, the restaurant became a golden-brown cultural mosaic, representing in a highly segregated era a meeting place for people of different backgrounds who shared a common hunger for burgers and conversation.

Chrys Kelekis held court at the countertop with people like future Winnipeg mayor Stephen Juba, the NHL star/bowling alley owner Bill Mosienko, the North End-raised television host Monty Hall (née Monte Halperin), and city councillor John Blumberg.

“At the counter, they tried to solve the problems of the world,” recalls Barb Hall, of no relation to Monty.

In 1957, while undergoing a medical procedure, complications with the anesthetic led to Chrys Kelekis’s death, aged 69.

But the end of his life did not spell the end of his restaurant: he had at least seven apprentices not far away who each shared his last name and his business acumen.

The sisters Kelekis ran the show.

SUPPLIED Uniformed staff and family members at C. Kelekis restaurant.

Sophie became the manager, and steered a tight ship, often telling her cooks to make a meal again in order to make it perfectly. “Some people thought she was a tough nut, but in fact, she was a marshmallow,” says Barb Hall. All the daughters had their roles, but each did a little bit of everything. Evelyn, Hall’s mother, was the master of the fryer, dropping in the shoestrings every day and cleaning out the machine every night.

Isabel greeted the customers during lunch and dinner hours, with her husband Bill seating the diners at their tables or atop one of the lunch-counter stools. She also took on cash register duties when her sister Chryse was greeting. Becky, the only Kelekis daughter still living, helped out in all facets, taking care of their mother and serving as bookkeeper.

Leo did not work as close to the food as his sisters, but as a practising lawyer, with a practice in Elmwood, he took on much of the administrative work. “There were very few squabbles among the girls because he would defuse any hint of conflict,” says his niece Hall.

WAYNE GLOWACKI / FREE PRESS FILES Owner Mary Kelekis holds court at the counter the day before the restaurant closed in 2013.

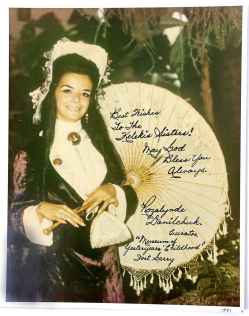

The irascible Mary, who co-founded Folklorama and was a tireless community volunteer, held the unofficial title of grillmaster. “She could whip up dozens of hot dogs and hamburgers in record time,” says Hall. “I’m sure she could have won a contest.”

Some employees worked at Kelekis for as long as 40 years, and would regularly return for guest shifts.

As customers walked into the restaurant, they were greeted first by a Kelekis girl and then by a large map, mounted on the wall before the dining room. Stuck into cartographic locations of cities like Dayton, Ohio and Baghdad were ball-topped pins, each one representing a place where diners had come from. By the time the restaurant closed in 2013, the map looked more pin than paper.

Around the corner, in the back, there was a medium-sized dining room. One wall was adorned by a mural depicting the Kelekis story. On the others were framed and autographed photographs of customers of note, known as the Kelekis Wall of Fame.

The wall was Chryse’s idea, and she decided who belonged, says Hall. Hundreds of people were selected for the honour, and it didn’t ultimately matter whether their fame extended beyond the Perimeter.

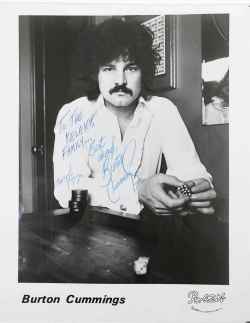

On the wall was the Let’s Make a Deal host Monty Hall, who reportedly used kelekis@yahoo.com as his email address. There were local bands, like the Guess Who and Bachman-Turner Overdrive, that are still spoken about today. There were others, like the Escorts or the Discovery, which have since faded from popular memory. There was orchestra leader Paul Grosney and the multi-talented performer Maxine Ware. Children’s television star Mr. Dress-Up, whose off-screen name was Ernie Coombs, ate there too.

Winnipeg-raised comedy legend David Steinberg, who endorsed Kelekis hot dogs as the best in the world — including, allegedly, to Tonight Show host Johnny Carson — signed his photo thusly: “I’ve made it. I’m on your wall.”

There were also politicians. Every premier from Sterling Lyon through Greg Selinger walked in. Jean Chrétien ate at Kelekis and signed an eight-by-10. In 1974, prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau stared with what appeared to be great confusion at a hot dog before taking a bite, flanked at the countertop by Izzy Asper, then the MLA for Wolseley and the leader of the Manitoba Liberal party.

However, no matter their status, every diner had to go down the dark staircase to the basement to use the bathrooms.

Amongst the biggest names were a vast collection of relative unknowns, such as Itz Jacob, who won the Kelekis-Blumberg Golf Tournament in 1974. There was also a photograph of a girl named Audrey Freeman, a teenager who played left field for the St. Vital Tigerettes beginning in 1941. After every game, the Tigerettes sat at the Kelekis soda counter.

On June 18, 1947, when she was 22 years old, Freeman was asked to pitch during a girl’s senior softball game toward the end of the season against the St. Boniface Athletics. The Tigerettes coach wanted to save the starting rotation for the playoffs. “Well, she ended up pitching a no-hitter,” says her son Wil Henderson.

“Audrey Freeman, the girl that just isn’t supposed to be a pitcher, picked the booster night to hurl her team to a 7-0, no-hit no-run victory,” proclaimed the Winnipeg Tribune.

Freeman, who became Henderson, and her family moved to Calgary soon after, and she didn’t return to Kelekis until the 1970s. From behind the counter, one sister poked her head up. “Audrey?”

“You know, your mom was a pretty big deal around here back in the day,” the sister told Henderson.

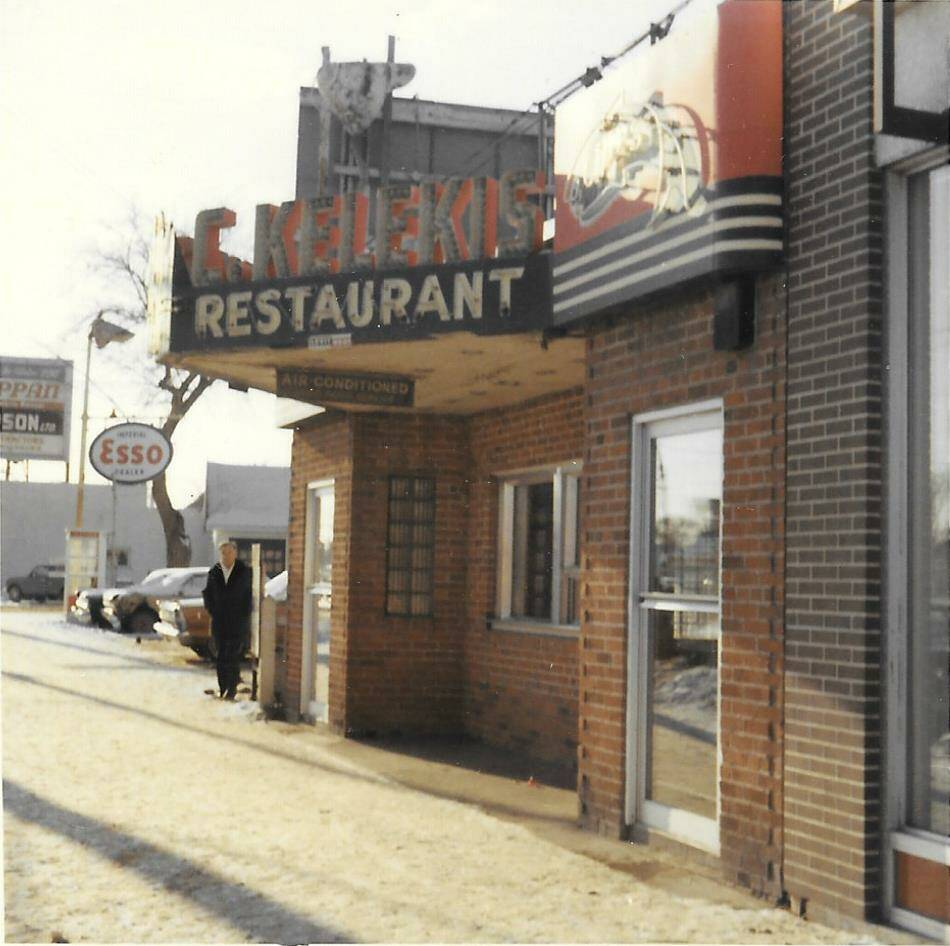

SUPPLIED The iconic storefront of C. Kelekis near the corner of Redwood and Main

Years later, the family returned for dinner during another visit to Winnipeg, when one of the sisters grabbed Audrey’s hand. “There’s someone I want you to meet,” the sister said.

She led the former Audrey Freeman to the other side of the restaurant where she shook the massive hand of the Golden Jet.

“Audrey, this is Bobby Hull. Mr. Hull, this is Audrey Henderson,” the sister — Henderson can’t remember which — said. “She has her picture up on the wall, just like you.”

“(He) shook my mom’s hand and said he was pleased to meet another ‘wall-hanger,’” says Henderson.

As the Kelekis sisters aged, the next generation of the family chipped in. But ultimately, in November 2012, Mary Kelekis decided it was time to shut down. On Jan. 30, 2013, the ‘open’ sign would be turned off forever.

“I’m 88 next month and it’s time,” she said. “That’s the way it goes.”

That triggered a panic, with customers rushing to eat at Kelekis one more, or 20 more, times before it shut off its fryers and flattops.

SUPPLIED A place setting and menu from C. Kelekis.

One pair of customers, best friends Daniel Kroft and Max Lerner, went to Kelekis for the first and last time right before it shut down, ordering the Yaleburger, named for their shared relative.

On the shop’s final day, the Kelekis staff worried whether they would have enough potatoes in the downstairs storage room to meet the demand. It made no sense to order more, but they considered it. When the final debits were made to the cash register, Barb Hall, whose mother Evelyn was the chip-maker, grabbed a few potatoes to make one final bowl of shoestrings. She shared it with her aunts and her cousins.

“There weren’t any left,” she says.

The recipe is not so much a recipe, Hall insists. “It’s a process.” But the other family secrets are out there: the week the restaurant shut down, a book containing recipes hand-written by Sophie was stolen.

Somewhere, a thief is enjoying a cup of coleslaw.

When Kelekis closed down, for the first time since the 1940s, 1100 Main St. had a vacancy.

No restaurateurs stepped in to purchase the building. Instead, a flower shop called Bloomex, which at first displayed coffins and funerary urns in the window, bought the classic diner.

“Every month or so someone comes in and asks for a hamburger,” says Leslie Borys-Hamilton, the floral distributor’s manager. She gestures to the counter behind her. “I say, ‘The grill’s tucked under here, so good luck waiting.’”

The interior of the former restaurant has been painted a lilac purple. Where potatoes were once cut, tulip stems are now snipped. The light switches are still labelled “kitchen” and “gourmet.” There’s a sign in the basement meat freezer reading “Do not place heavy objects on rolled hamburger.” The potato room no longer contains any potatoes.

RUTH BONNEVILLE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS The chipper from C. Kelekis

The back kitchen has been removed, as have the booths, and tables. All of the photographs, along with table settings, the old toaster, and a few menus are archived at the Manitoba Museum. The chipper was purchased by the steakhouse Rae and Jerry’s, but it broke down shortly after arriving.

Inside what was once the Kelekis pastry cooler are ribbons, zip ties, tape, and cat food. “We have a cat,” Borys-Hamilton said.

Coming to work every day, Borys-Hamilton is met with a constant sweep of nostalgia. Many frequent Bloomex customers were also Kelekis fanatics, including a 72-year-old man named Gary, who walks in on Feb. 13 to buy a Valentine’s bouquet.

“How much will you charge me for a bunch?” he asks. “$25 to $35,” she replies.

“Who do you think I am?” he jokes.

“You love her, don’t ya?”

He hands over the cash, and leaves with his flowers tucked under his arm.

RUTH BONNEVILLE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Lesley Borys-Hamilton works at Bloomex, the florist that now occupies the building Kelekis made famous. Borys-Hamilton has fond memories of the eatery, as she and her husband had their first date there.

Borys-Hamilton smiles when asked if she went to Kelekis before it closed.

“Of course,” she says. “Me and my husband had our first date here. We sat right around the corner and split a cheeseburger with mustard, onion and pickle.”

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.