Resources, reconciliation and Wetiko

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/02/2023 (975 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

For Manitoban author, filmmaker and environmentalist Clayton Thomas-Müller, healing is about connection to the land.

His family hails from Pukatawagan, also called Mathias Colomb Cree Nation, in northern Manitoba, but Thomas-Müller spent much of his life in Winnipeg’s west end. His story, laid out in his 2021 memoir Life in the City of Dirty Water, journeys through the trauma of his early life and his continual connection to the land, the rivers and his family’s trapline in Puk, as he calls it.

Over the last 20 years, Thomas-Müller has embedded himself in environmental and Indigenous justice organizing. His work has grown from downtown Winnipeg youth programs to speaking on Indigenous and environmental justice before the United Nations, to campaigning with a host of national and international environmental organizations. His work focuses on the deep ties between colonization, displacement, resource extraction and the climate crisis.

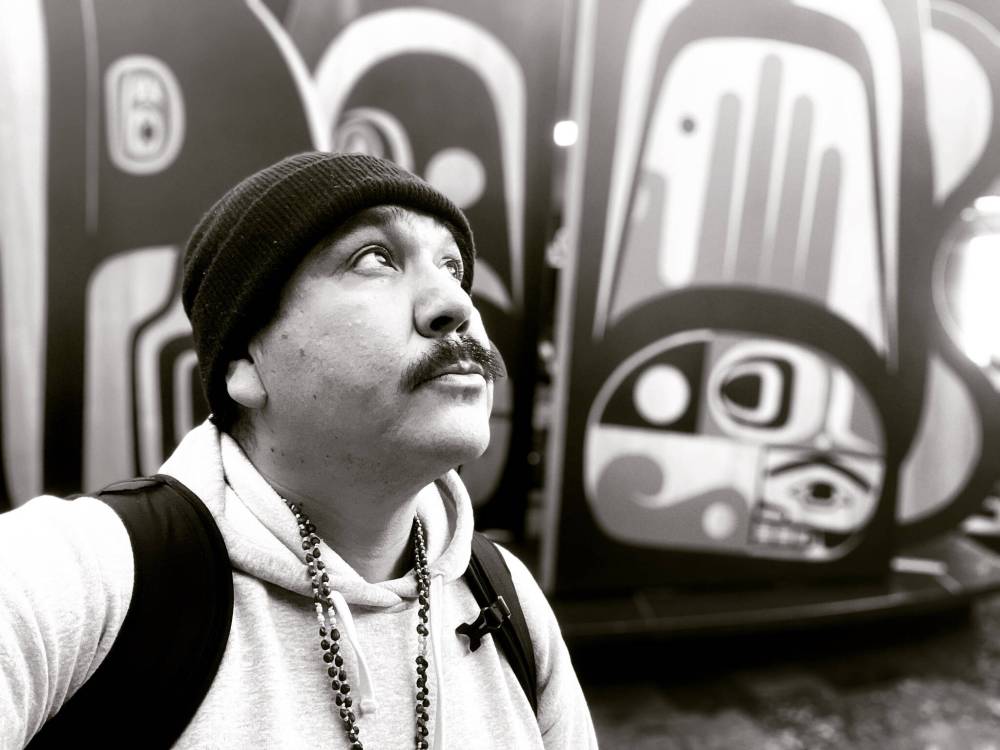

SUPPLIED

‘Putting a net in a lake, pulling it out, getting fish and building a smoker to dry your fish — these are things that everybody needs to experience,’ Clayton Thomas-Müller says, offering one view of personal reconciliation.

In advance of his Wednesday talk, titled Pathways to Sustainable Communities, at Winnipeg’s Park Theatre, we spoke about the connected crises facing not only Indigenous Peoples, but Canadians as a whole — and what needs to be uprooted for healing to grow.

You were in Winnipeg to talk about colonialism, resource extraction and the environment. What draws you into this kind of work?

What brought me into this was suffering. One thing that Native people share, aside from a lot of our cosmology and worldview in terms of the sacredness of place, is our shared experience when it comes to colonization.

Everywhere I go I see the same thing: if you trail back long enough in a family history — and it’s usually only one or two generations, if not that generation — you find unique stories of displacement usually pinpointed to a corporation, or the military or some kind of colonial power.

Can you speak to the long-term impacts of displacement caused by resource extraction?

We’re dealing with this incredible sickness, like a plague, and it’s tied to capitalism and colonialism. In my culture we talk about the rapacious Wetiko spirit. If you get possessed by the Wetiko, you turn into a cannibal. If you encounter a Wetiko, you notice they’ve eaten off the tips of all their fingertips; a Wetiko will eat their own family. It’s not necessarily evil, in our worldview there’s not good and bad, just balance. But if you let the Wetiko out, the Wetiko destroys the world. I believe this sickness the Wetiko brings, this insatiable hunger, is only accelerated by hyper-individualistic consumerism and capitalism. I believe we’ve created such an incredibly bad imbalance across Mother Earth and we’re now coming to terms with that in the context of hard-core climate science.

How have your home communities, Pukatawagan and Winnipeg, been impacted by resource extraction?

For me, there’s a deep spiritual wound, a scar on every Cree person’s heart, with what’s happened to our rivers. Our entire life was based on the river. We would travel at night, with the other animals, on the dog sleds up the ice. We can’t do that safely anymore because of the fluctuation of the water levels. We can’t put our nets in some areas under the ice because, again, of the fluctuation of the water. In the summertime, there are entire islands that have disappeared on my trapline because of the fluctuating water levels and the erosion that occurs when the water goes up and down. The hydroelectric dams were one of the most violent things ever to happen to our people. A lot of people don’t understand that Native people from where I’m from, who live in the city, are environmental refugees.

SUPPLIED

Author, filmmaker and environmentalist Clayton Thomas-Müller hopes that reconciliation and resource extraction happens in the big picture as well as on the personal level.

How do you envision a solution to the interconnected issues of resource extraction and environmental crises?

All solutions to things like the existential threat of climate change point locally. At the end of the day the solution to climate change is community self-determination over our water, our sanitation, our food production, housing distribution, energy — especially energy — and transportation.

That emptiness inside, that hyper-individualism and hunger that the Wetiko spirit causes, we fill it with consumerism but the only way to really fix that sickness is by connecting to the sacredness of place by connecting to nature.

As we start to see more and more visceral impacts of climate change in urban centres, what lessons do you think settlers can take from Indigenous Peoples who have had to face these changes time and again?

Native people are the experts at rapid adaptation and migration because we’ve been forced to become good at it.

We carry these vast libraries of ecological knowledge: millenia of intentional observation; trial and error; and the development of an apex species’ ability to manage an ecosystem in a non-ownership way. For me, this is why language and culture — not just going to ceremonies, but actually getting to go stay out in the bush, to go berry-picking, to have the experience of putting a net in a lake, pulling it out, getting fish and building a smoker to dry your fish — these are things that everybody needs to experience.

I also think people need to stay committed to that conversation — that 60,000-foot question of what it is actually going to take for us to heal from the violence of colonialism. That’s a big question that’s going to take multiple generations to answer, but there are concrete, real-time solutions right now that can address the economic imbalance that exists, the disparity that exists for Canada’s most marginalized population. There are steps we can take in terms of the suite of legislation that this government needs to pass in order to deal with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 recommendations and the suite of legislation this government needs to pass in terms of a just transition in regard to climate change and decarbonizing our economy.

We need to get our fossil-fuel intensive agriculture sector off fossil fuels, we need to get our truck and transport sector off of fossil fuels. That’s a huge responsibility that quite often, I think, freezes people in place. It can be very daunting. That’s why I go back to community self-determination and the small acts. We need to be focusing on what builds power in our communities.

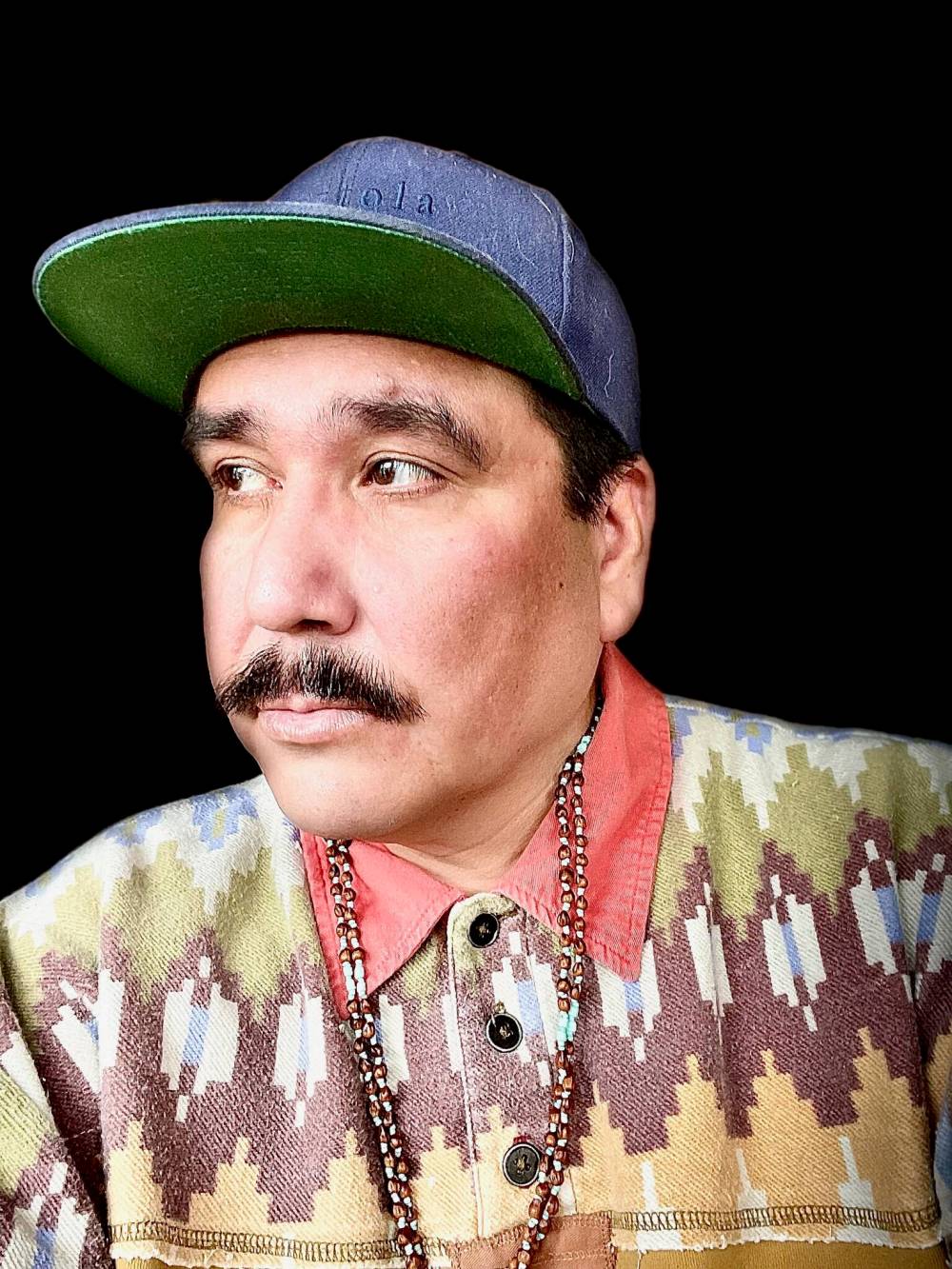

Spencer Mann photo

Author, filmmaker and environmentalist Clayton Thomas-Müller hopes that reconciliation and resource extraction happens in the big picture as well as on the personal level.

How do you put those solutions in motion in Manitoba?

Whatever Canada does in terms of political, economic or social reorganizing in relation to the existential threat of climate change is inextricably tied into whatever actions Canada, the settler-colonial state, takes on the implementation of the 94 recommendations on Truth and Reconciliation. We have to be very mindful to look at things in a collective way, not compartmentalize things, because every part of our life is impacted by these things.

Here in Manitoba, my ancestors’ graves are currently under a massive hydroelectric reservoir created when they built the dams and dammed up our highways — the rivers. My dream is that we would one day see those dams decommissioned, and those places that were flooded would again see the light of the moon. That’s what reconciliation looks like to me.

There are huge opportunities to really honour the spirit and intent of the Treaties when we talk about climate change and just transition. There are a million opportunities and job creations that this huge challenge presents us. The thing we have to do right, as a society, is to make sure that those hit first and hit hardest by the transition off of fossil fuels are first in line with the new economy — and that’s Indigenous Peoples.

julia-simone.rutgers@freepress.mb.ca

Julia-Simone Rutgers is the Manitoba environment reporter for the Free Press and The Narwhal. She joined the Free Press in 2020, after completing a journalism degree at the University of King’s College in Halifax, and took on the environment beat in 2022. Read more about Julia-Simone.

Julia-Simone’s role is part of a partnership with The Narwhal, funded by the Winnipeg Foundation. Every piece of reporting Julia-Simone produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.