Film Group comes into focus

New book traces how Winnipeg’s dedicated cinephiles came together nearly 50 years ago

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/04/2023 (984 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

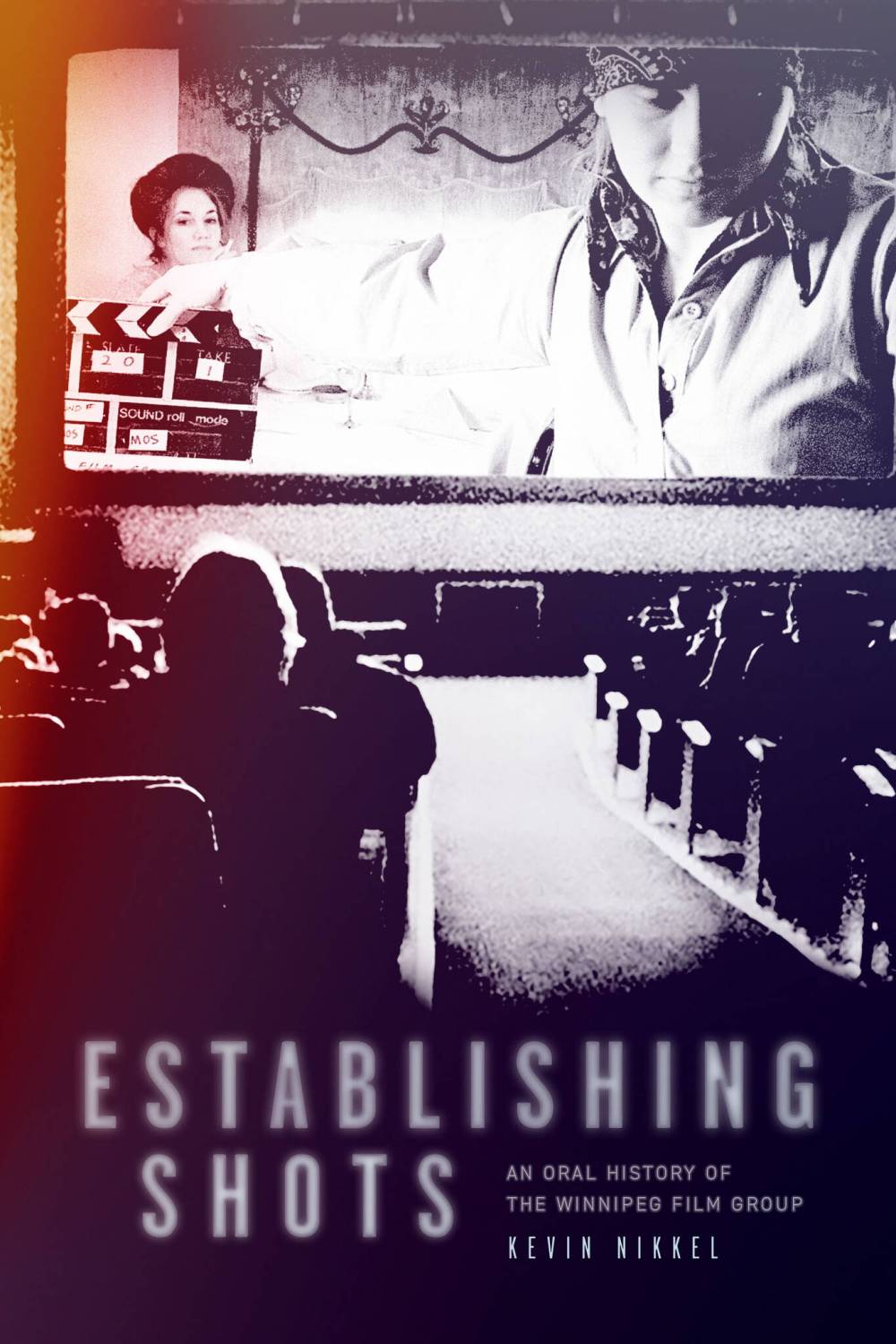

Excerpt from Establishing Shots: An Oral History of the Winnipeg Film Group, by Kevin Nikkel (University of Manitoba Press). A book launch will be held April 12 at Dave Barber Cinematheque.

I imagine a well-worn path in the snow leading to Leonard Klady’s house. An assembly of the same people most Sunday nights, like some sort of religious cult. They gather in a darkened room to watch a print on a 16-mm projector (this being the early 1970s). Klady’s uncle was a film distributor and he brought home 16-mm features every weekend for this dedicated crew of cinephiles. This group, existing in a marginalized city, was about to experience an infusion of new energy and purpose.

Several circumstances acted as catalysts upon this group of film enthusiasts. Film studies courses had begun to be offered at University of Manitoba, as across Canada. In the hinterland regions, individuals were searching to find a voice in what Andrew Burke describes as the “long” 1970s and the “afterglow” of Canada’s centenary celebrations. The protests of the era evoked a spirit of collective action and the need to organize. These factors would set the stage for Klady to organize a national film event in Winnipeg.

PHOTO COURTESY OF BRAD CASLOR

Members of the Canada Council meet with Winnipeg Film Group representatives in the Bate Building, circa 1970s

The Canadian Film Symposium was held in 1974, during the University of Manitoba’s weeklong Festival of Life and Learning. A chance for students to skip classes, watch films and hear lectures, it even included a free concert by the then unknown band Kiss. Expectations were high. Insiders came from across the country to discuss Canadian filmmaking. Cinema Canada journalist Agi Ibranji-Kiss called the week-long event a “merry-go-round” of activities, “running from 10 in the morning to early the next.” Representatives from various funders, distributors and filmmakers used the event to provoke serious discussion. Apart from the premières, cathartic panel discussions allowed Canadian filmmakers to vent about the state of their craft in the face of federal inaction. From the “gloomy mood” of the Film Symposium emerged a written declaration:

The Winnipeg Manifesto:

We the undersigned filmmakers and filmworkers wish to voice our belief that the present system of film production/ distribution/exhibition works to the extreme disadvantage of the Canadian filmmaker and film audience. We wish to state unequivocally that film is an expression and affirmation of the cultural reality of this country first, and a business second. We believe the present crisis in the feature film industry presents us with an extraordinary opportunity.

For the group that met to watch films at Leonard Klady’s house, this was a chance to meet others, filling in their ranks. A local panel discussion was convened that included Klady, Robert Lower, Neil McInnes, Jerry Krepakevich, Ian Elkin, Leonard Yakir, Dave Dueck, Gunter Henning and Leon Johnson. This local panel would prove a catalyst. Penni Jacques, from the Canada Council for the Arts, spoke to the enthusiastic group of locals and encouraged them to form an organization that could be funded by the Council. Two weeks later, members of the new Winnipeg Film Group formalized a “Statement of Principles, Objectives and Structure.”

The Winnipeg Film Group joined a wider movement of artist-run centres happening across Canada, some founded as co-operatives and others as non-profit corporations. In all, there would be 16 artist-run film centres. The movement represented an effort to decentralize resources available to film-based artists through the funding for artist-run centres. Some organizations specialized in distribution, production, training and/or exhibition spaces, and most also filled a gap as drop-in centres for artists. In a city of Winnipeg’s size, the Winnipeg Film Group embodied multiple roles under one roof. The artist-run centres were networked together through various organizations such as the Independent Media Arts Alliance (IMAA). AA Bronson has suggested the phrase “connective tissue” to describe the dynamic networking of individuals within artist-run centres and between centres across the country — essential for developing the extensive art scene we observe today in Winnipeg and across Canada.

Still, the local visual art scene was not completely harmonious. Individuals who emerged from institutions such as the School of Fine Arts at the University of Manitoba did not integrate easily with the crowd that gathered at the Winnipeg Film Group. In the early 1980s, one stream of creatives sheared off to form Plug In’s Video Forum and Video Group, leading to the founding of Video Pool in 1983. Video Pool maintained a distinct identity from the Film Group; co-operation was selective, with suspicion on both sides.

The Bate Building

The Winnipeg Film Group’s first home was established in the Bate Building in Winnipeg’s Exchange District, a dusty structure typical of the declining neighbourhood in the years before gentrification. The Group held regular meetings — gatherings which, due to the copious cigarette smoke, might have been mistaken for AA meetings. The Film Group occupied itself with existential questions and the office acted as a clearinghouse for members. Leonard Klady and Leon Johnston were in charge of writing grants for operating funds, equipment purchases and to support film production.

Establishing Shots: An Oral History of the Winnipeg Film Group, by Kevin Nikkel

There were two poles at the Film Group during these formative years: activists and artists. The former saw film as a hammer to change the world, the latter a brush for self-expression. This enthusiastic group of filmmakers demonstrated the essential qualities of emerging artists: energy, optimism and innovation. Several collective projects offer case studies illustrating how the Group was learning to define itself and work together.

In the summer of 1975, a crew of Film Group members began shooting a documentary about the Winnipeg Folk Festival. The project was shelved for a lack of vision and insurmountable technical problems. A second collective effort was shot the same year: a silent-era-inspired comedy, Rabbit Pie (1976), in which a couple discovers that their restaurant meal of rabbit pie is multiplying all over their table.

In contrast to the failed attempt at a Folk Festival film, Elise Swerhone’s documentary Havakeen Lunch (1979) — a film that observed the last days of a small-town lunch counter — was a much more confident success. Swerhone found funding for her project elsewhere but obtained equipment from the Film Group, a path that others replicated. David Cherniack’s unfinished character-driven drama The Crunch began this way; partially funded by the Film Group, it stalled at rough-cut stage. The Crunch exposed a rift over which films should get funding — some felt the project was not worthy. Questions surfaced. What should be the Film Group’s role in terms of production? Should the Film Group be a producer of its members’ films? The debate simmered right up to the late 1980s, with Gene Walz’s short comedy The Washing Machine (1988) in which a couple struggles over their faulty appliance — a metaphor for the Film Group itself during this era.

Inside the Film Group, the institution’s maturity was marked by the acquisition of a photocopier. Not everyone was as enthusiastic about spending precious grant funds — money that could go toward film production — on office appliances. Ed Ackerman and Greg Zbitnew’s response was 5¢ a Copy (1980), an animation made from photocopied faces and eclectic objects. This office conflict reflected the inevitable friction present in artist-run centres between bureaucracy and artistic practice. For the Winnipeg Film Group at that time, 5¢ a Copy represented an alternative to a growing number of social realist documentary productions. A core of the Film Group was more interested in artistic expression and pushing the edges of experimental film than in changing the world.

Although its tides ebbed and flowed greatly, during this period the Film Group was marked by a high level of community engagement; but as the National Film Board (NFB) expanded its presence in Winnipeg with money for regional projects, many of the Group’s founding members saw this as their chance to find paid work elsewhere. The Film Group would need to find ways to evolve.