The meteoric rise and tragic fall of the Toilers A Canadian dynasty in the early days of the sport of basketball, Winnipeg’s hoop heroes’ dreams of international glory crashed down to Earth in a Kansas corn field nearly a century ago

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/04/2023 (970 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In basketball, to be told you have no right hand is an insult akin to telling a bassist they have no sense of rhythm, or a poet they know not what it means to suffer.

Without the presence of a second competent dribbling hand, a defender can be certain which direction the offensive player is headed when they roll to the basket for a layup. Without the threat of a crossover, there is little space for surprises.

The potential energy of the ball as it rocks steadily like a metronome — from right hand, to left hand, and back again — is the open secret that separates the good basketball players from the great ones.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS A.C. (Colonel) Samson served as team president.

What was left of A.C. (Colonel) Samson’s right hand was a knob and a thumb, with the stubs of his fingers jutting out like crooked tombstones.

The accident happened in 1895, four years after the game of basketball was invented by an Ontarian theologian and athletic experimenter by the name of James Naismith, who through round glasses saw the future of team sports in the form of peach baskets and hardwood floors at the Young Men’s Christian Association in Springfield, Mass.

Despite his name, the Colonel’s injury was not military in nature, but that did not mean it did not occur in the line of duty.

Allan Connell Samson was born in the middle of a pack of 13 children in Edinburgh, and was carried across the Atlantic Ocean as a six-month-old to Winnipeg, where he grew up quickly. Shortly after finishing his grade school education, the pre-teen went to work for the Manitoba Free Press, where the boy became a pressman.

With hands not yet altered by gravity and time, he learned to work the machinery, living behind the scenes and witnessing through his fingers the stories of a changing city and world.

It was a dangerous job, and a thankless one; the pressman does not get a byline. But the Colonel took pride in the work, even as the tools of his labour ensnared his dominant hand in their unforgiving gears.

The Colonel adapted: he relearned to grip a pen and how to wield a fishing reel, which he would use to cast out at West Hawk Lake, where a bay now bears his family name. But it went without saying, in those insensitive days, that without a right hand, basketball was not a sport for him.

However, the Colonel’s friends and colleagues from the YMCA adored the game, and the novelty of building a legacy in what was then a new sport.

Basketball was dismissed by some as a fad, and was considered to be somewhat juvenile. But even before the alley-oop and the three-pointer, the game had a jazziness to it, even in its freshly invented terminology and its more rigid, infant form, built around set plays, not fast breaks. The ball was bounced and swung, and the players aimed for a swish, longing to avoid the percussion of a rimshot.

In Winnipeg, William Alldritt, the British-born YMCA assistant physical director and a staunch United Christian, saw basketball much as did Dr. Naismith, who was a Presbyterian minister: the ultimate team sport, where sharing the rock was the only way to advance a communal cause.

In October 1910, Alldritt, 39, and a few other YMCA regulars, including a man known as Waddy Ferguson and another called Steppy Fairman, decided to put the game’s promise into practice, drafting the founding papers for a men’s basketball team to be based out of the downtown gym.

Destined for hard work, and in fear of and in service to the Lord, they called themselves the Winnipeg Toilers.

Just west of a looping Red River, across from the western point of what is now Kingston Crescent, the young and eligible bachelor Waddy Ferguson had bought himself a slice of land.

Ferguson was an original Toiler, known for a strong set shot and tenacious defence, defining traits for those early Toilers teams, according to newspaper accounts.

JOHN WOODS / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Toilers Park on Riverside Drive.

On the property, which today would have cost him millions of dollars, Ferguson lived alone, but he also set up, with Alldritt and the YMCA’s support, a training camp, where each year, the Toilers would prepare for their season, in which they’d vie for the city and provincial championships.

Some players were fixtures at Waddy’s for the better part of the 1920s and 1930s: George Wilson, a star forward who, with his family, operated a Main Street furniture shop; Hugh Penwarden, a diminutive forward known by fans as Mickey Mouse; Ian Wooley, a skilled big man; Bruce Dodds, an athletic guard; and Lauder Phillips, a powerful centre from Winnipeg’s North End who stood at 6-foot-1 and was employed as a sheet-metal worker at the Canadian Pacific Railway’s Weston Shops.

In addition to studying the playbook, the team spent a good deal of time studying the good book. But Ferguson was a bachelor, so Toilers Camp became known as a party spot.

In the 1920s, as the Toilers began a run of seven consecutive Crowe Trophies as Winnipeg’s top amateur club, the Colonel, by then the team president, was invited one evening for what turned out to be a blind date with a woman from Virden named Eva Larmer. He didn’t like the name Eva, he joked, so he asked if he could call her Larry. She said yes.

Larry and the Colonel were married on the cusp of the economic crash of 1929, which sent Larry to work as a registered nurse to buttress her husband’s pressman income, which remained steady as his employer, then the Winnipeg Tribune, kept printing.

By 1932, the Colonel and Larry had one son, with a daughter on the way, and the Toilers had blossomed, under the management of their former star George Wilson, into the top team in the country.

“This was at a time when senior men’s basketball was the highest level played. Better than university, high school or junior,” says Ross Wedlake, the chair of the Manitoba Basketball Hall of Fame and one of the province’s foremost historians of the game.

“In other words, they were the best.”

“This was at a time when senior men’s basketball was the highest level played. Better than university, high school or junior… In other words, they were the best.”–Ross Wedlake

In that year’s western final, the Toilers faced off against Alberta’s Raymond Union Jacks, a bitter rival who lost to the team the previous year by default because their court was in an opera house, and the stage was deemed too close to the baseline.

The Toilers “did not want to endanger their players by playing in a barn,” according to Naismith To Nash, an invaluable resource for early Canadian basketball history.

The Union Jacks were irate and threatened to leave the athletic association. Their coach Dave Powelson asserted in the Lethbridge Herald the Toilers were vindictive over past losses. “The Toilers are merely trying to win titles in the executive committee room which they are not willing to play for on the gymnasium floor.”

When they met in the next post-season, the Toilers swept the Union Jacks in two games, winning 33-30 and 36-23 to advance to the Dominion championship.

Of the Toilers’ 69 total points, a 20-year-old sharpshooter named Joe Dodds, the younger brother of Bruce, scored 23, and Mike Shea Jr., in his first season with the club, added 12. Lauder Phillips, then 22, scored 13.

SUPPLIED The Toilers ruled the Canadian basketball scene in the late 1920s and 1930s. Back row (from left): Lyn Sinclair, coach; A.C. Samson, president; Lauder Phillips; Al Silverthorne; George Wilson, manager; W.A. Alldritt. Front row (from left): Ron Burgess;, Bill Thorogood; Mike Shea; Ian Wooley, captain; E. Pearson; Joe Dodds; and W. Walkey.

The team was loaded with local talent and athletic eminence: Al Silverthorne, 27, had been a star at Kelvin High School; Ian Woolley, 27, was the team’s stretch-centre, able to play guard as well, and the younger brother of Foster Woolley, who played for Canada at the 1932 Winter Olympics at Lake Placid; Hugh Penwarden was a champion lacrosse and soccer player, the brother of Reg Penwarden, the top sprinter in Manitoba; Mike Shea’s father was the sports editor of the Winnipeg Free Press.

The Dodds brothers were stars, frequently deploying a long set shot, which today would be worth three points.

With a third national championship on the line, the Toilers played the Saint John Trojans on their New Brunswick turf. In the first game, a bucket by Silverthorne beat the buzzer to give Winnipeg a 39-37 win. In Game 2, Shea, with 10 points, single-handedly equalled the Trojans’ entire offensive output.

The Toilers returned to Union Station, received by a champion’s welcome.

News spread south of a rising dynasty, reaching the managers of the Tulsa Diamond Oilers, a team rich in resources both natural and financial.

Sponsored by the Mid-Continent Petroleum Corp., the Diamond Oilers, led by an all-American forward named Charles Hyatt, were the national champions of the American Amateur Athletic Union circuit, cementing them as the best team in the U.S.

More than a decade before the inception of the National Basketball Association, the sport’s promoters were seeking a way to legitimize their noble game.

Thirty years earlier, the commissioners of the American and National Leagues had a similar notion: with their game of baseball attaining mainstream attention, they decided it would be a marketing bonanza to pit the winners of both leagues in an ultimate head-to-head matchup that became known as the World Series.

WINNIPEG FREE PRESS ARCHIVES The Toilers’ bid for North America supremacy came up short against a powerhouse squad from Tulsa, Okla., the Diamond Oilers. A crowd of 2,000 watched the teams battle it out on the court.

Here was the pitch the Mid-Continent Petroleum Corp. made to the Colonel and Wilson: the Toilers will travel due south to Tulsa, Okla., to face the Oilers in a two-game series, followed days later by a two-game set in Winnipeg.

Mathematically, it did not make sense: a split was possible. But the Oilers were confident they could handle their northern opponents, while also spreading goodwill for the game.

Today, basketball is one of the world’s most globally popular sports, as beloved in the Philippines as it is in Springfield, Mass., where Dr. Naismith tossed the first jump ball.

In 1933, it was still considered by the uninitiated as a novelty act. Basketball was today’s pickleball — not quite a sport, but not quite a game, in the eyes of the establishment.

It was an intriguing offer to the Colonel and to Wilson. Via telegram, they agreed. A date was set for the trip to Tulsa: March 30-31, 1933.

As the game neared, Alldritt lay dying, but it was not the first time his demise was reported. Eighteen years earlier, in a battle in Langemarke, Belgium, not far from Flanders Fields, he was noted as killed in action. Alldritt was believed dead, and news reached home, but for 35 months, he was eking out survival as a prisoner of war, held by German forces. He escaped.

But now Alldritt, the team’s founder, was factually gone, age 52.

The team gathered in the YMCA gymnasium for the memorial service, presided over by Rev. J.F. Stewart. Alldritt was remembered in readings as a soldier, a sportsman and a Christian citizen.

“Abide with me, fast falls the eventide,” the congregation sang. “The darkness deepens; Lord, with me abide. When other helpers fail and comforts flee, help of the helpless, O abide with me.

“Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day; Earth’s joys grow dim, its glories pass away. Change and decay in all around I see. O thou who changest not, abide with me.”

Four days after the funeral, the Toilers would take a train to Minneapolis and board a Ford tri-motor plane for Tulsa.

Five days later, that plane would take a nose dive, jack-knifing through a cloudless morning sky into a Kansas cornfield still wet from the first rainfalls of spring.

The plane had wicker seats and no seatbelts.

It also had three 220-horsepower motors and a carrying capacity of 14 passengers and as many as 13,000 pounds.

Purchased by an early aviation investor named Jeff Kenyon, the ‘Three Hawks’ plane was built by the Ford corporation in Detroit and flown for the first time on Nov. 27, 1928, by Paul Quinn, who considered the small aircraft his favourite.

It had been a barnstormer in air shows in the U.S., Canada and Mexico, but was by 1933 used mostly for short-distance charter flights. It had 170,000 miles of air service.

“I have flown that ship through rain, sleet and snow and never at any time, to my knowledge, had it ever been scratched.”

The aircraft was in good enough condition for Morris, Minn., farmer J.H. O’Brien to buy it from the Kenyon Transportation Co. as a retirement gift to himself and as an investment in a second career as an aviator.

Throughout their 23 years of play, the Toilers travelled exclusively by train for games outside their city.

With domestic flights still considered a luxury, the flight to Tulsa from Minneapolis was the first aerial adventure for many, if not all, of the players, along with the Colonel, accompanying the squad as team president, and also as a civic representative of Winnipeg mayor Ralph Webb.

The first flight should have raised concern.

“We arrived with not too much difficulty,” George Wilson said in an interview on file at the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame.

“One engine caught on fire on the way down, and we had to stop at Omaha and get that put out. And while we were there, the pilot flew people all over town or around town for $5 apiece to try and make up his losses.”

When the team finally arrived in Tulsa, they stayed at the Bliss Hotel, a zigzag, art deco-style building made of terracotta and brick.

Ten storeys high, it was right next to Tulsa’s own Union Station. The hotel’s proprietor welcomed the team with a telegram.

“Although we cannot wish your team the success of winning the title from our city and nation as the world’s greatest basket ball team, we do extend you our sincere hope for a safe and pleasant journey to Tulsa and assure you your team will receive the most cordial welcome from the entire country and especially from the city of Tulsa and the Hotel Bliss.”

The games themselves were befitting of the World Series title, a grand affair that played out in front of a full house of 2,000.

In attendance was none other than Dr. Naismith, in town from his home in Lawrence, Kan., where Naismith — an accredited medical doctor — was for decades a member of the University of Kansas’s athletics faculty. The Colonel presented him with the key to the City of Winnipeg.

With the father of basketball sitting in the stands for the opening game, the Oilers rocked the Toilers 32-13 before throttling them 41-19 in the second.

But the Toilers endeared themselves to their opponents and the fans alike: Penwarden earned his Mickey Mouse nickname in Tulsa, where, like a cartoon character, he dove and scrambled for the ball, often emerging with the leather in his hand despite his small stature.

Understandably, the Toilers were eager to return home: Bruce Dodds was engaged to be wed; Lauder Phillips had work to do at the sheet-metal plant; and the Colonel was, as of Jan. 30, a new father to a baby girl named Jean.

The return flight left for Minneapolis just past seven in the morning.

The team had lost, and by some measures, had been embarrassed at the hands of the Diamond Oilers, but the mood on the plane was jovial. There was dancing and singing, and the players revelled in the opportunity of watching the fields below.

The Colonel had on a set of pince-nez glasses, holding in his hand a copy of that day’s newspaper, glancing over the box scores. He was an avid reader of science fiction, interested in anything that had to do with outer space. One can imagine his thrill at being able to hold his morning news while soaring above the Oklahoman landscape.

A photo of the Toilers team in front of the plane before that fateful flight in 1933. (l-r bottom row) George Wilson, manager of team, Andrew Brown, Hugh Penwarden, Al Silverthorne, Col. A.C. Samson (l-r back row) Lauder Phillips, Mike Shea, Bruce Dodds, Joe Dodds, Ian Wooley, Duce Belford of the Creighton university coaching staff, and A.A. Schabinger, director of athletics at Creighton. Neither Belford nor Schabinger were on the plane when it crashed.

Sitting next to him was J.H. O’Brien, who began to talk about the weather. He looked out the window and said they were flying over a place called Neodesha, Kan.; the plane had inexplicably gone off course.

Breaking the silent purr of the engine was a rattle, then a growl: one of the plane’s three engines had failed.

The plane swung west, then south, and the Colonel saw it was gliding downward, over a recently plowed field, for a clear pasture, tailor-made for an emergency landing.

Captain Alvie Hakes, the pilot, shut off the motors and took the Three Hawks down. O’Brien turned to the Colonel with a grim prediction.

“My god,” he said. “We’re gone.”

Eldon Vandenburg was feeding his hogs when he heard the plane crash.

The 18-year-old dropped his buckets and ran into his father’s fields, where he came across the gnarled wreckage of a plane and the wails of men where in a matter of weeks corn would grow.

“Let me out,” he heard. “Let me out.”

The plane was shattered, with the right wing flayed across the fuselage, trapping 13 of the 14 passengers beneath its weight.

In the distance, Vandenburg saw one tall man stumbling, dazed, confused, and in shock. Lauder Phillips had crawled through a gap in the fuselage.

He walked away with only cuts and scrapes, but some teammates, trapped beneath the wing, were soaked in oil and caked with mud.

Another farmer called the hospital to alert the authorities.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Jean Lothian, whose father A.C. (the Colonel) Samson survived the Toilers plane crash in 1933, flips through a scrapbook that chronicles the team’s triumphs and tragedy.

“We couldn’t budge that heavy wing,” Vandenburg told the Neodesha Register. “Phillips couldn’t help me much. He was dazed. And the injured began to beg me to help them.

“Phillips had been tugging at three of them and I helped him. We got them out, but I saw we couldn’t rescue anyone else, so I ran to the highway to flag cars.”

Several vehicles along Highway 29, which turns into Highway 75 at the Canada-U.S. border as it runs north to Winnipeg, stopped. With the strength of a dozen farmers, the right wing was lifted.

Six men were dead: Joe Dodds and Mike Shea, two of the Toilers’ youngest and best players; J.H. O’Brien, the plane’s owner; the pilot Hakes and the co-pilot Eggers; and Ray Bonynge, the Toilers’ sponsor and financier.

With little time to spare, the motorists collected the survivors and drove them into Neodesha, a town which, like Winnipeg, sits between two rivers.

The Wilson County Hospital had no beds to spare, and no doctors available either.

Sheila Shipley, the hospital’s superintendent, was tasked with rectifying both concerns. She telephoned nearby Independence and Fredonia to send four additional doctors.

“It was a bit of good fortune that the Wilson was the state’s first public hospital,” says Chris Bauman, a volunteer historian in Neodesha. It had opened its doors in 1923.

Drs. Randall, Williams, McGuire, Sharpe and Wiles were on call, as was Dr. Moorhead, whose son still practises medicine in Neodesha at age 83.

Inside the hospital, small-town doctors were dealing with a mass trauma event.

The Toilers’ Andy Brown was unconscious, his eyes swollen and plastered shut by mud. George Wilson’s back was broken. Al Silverthorne broke an arm and a leg. Bruce Dodd was in and out of consciousness, reports said, later laid up in a wheelchair. Ian Woolley was out cold.

When the Colonel woke up, he was missing his glasses and hearing the screams of a woman in labour down the hall. Aware of the tragedy the hospital was dealing with, the woman apologized for her shrieks.

An ambulant Colonel dismissed any perceived annoyance, delivering to her a bouquet of flowers to welcome her newborn son into the world.

He telegraphed Larry a message. “Dear kid, just received a few bruises. Everything fine.”

Bruce Dodds sent three important words: I am OK.

Lauder Phillips was the first survivor to wander the halls, and was led to the hospital’s morgue to identify the victims, according to an account by Kansan writer Joe W. Allen.

The crash site became a landing pad, with mothers, fathers, fiancées, and newspaper reporters flying into Neodesha

Meanwhile, the crash site became a landing pad, with mothers, fathers, fiancées, and newspaper reporters flying into Neodesha. Nearly 20 planes landed in the field where the crash occurred. Extra telephone lines were installed by the Bell company to accommodate extra calls.

For a few days, the population of 5,000 was inflated by the type of tourism no community seeks out.

One visitor to the hospital wore round glasses and a moustache: a 71-year-old Dr. Naismith.

When news of the crash reached him, Naismith drove from Wichita, Kan., to the scene of the tragedy, following the medical processional to the Wilson Medical Centre.

“The plane is in bits and it is a miracle that any of them survived the smash-up,” he told the Lawrence Journal-World. “I have never seen such courage as was exhibited by Col. Samson and the other survivors. Many of them are dangerously injured and are in pain, but their spirit is high.

“Such was also their conduct on the basketball floor, where their sportsmanship won commendation from those who saw the game.”

In Neodesha, locals offered whatever help they could: flowers were delivered to the hospital; the owner of the movie theatre offered free picture shows for any of the extended Toiler family; a man named Arzy Sharp found the Colonel’s glasses in the field and returned them without damage.

At home, Winnipeggers raised money to cover funeral and medical bills completely.

”Many of them are dangerously injured and are in pain, but their spirit is high.”–Dr.Naismith

Captain Ian Wooley regained consciousness the day after the crash, and recognized the face of Charles Hyatt, the Oilers star who had come to visit.

“You are the boys we went car-riding with,” he said, through eyes nearly swollen shut. “We must have had a bad accident.”

In bed, Bruce Dodds sat up straight, holding in his hands a small gold watch, attached by a chain to a knife. He had by then heard about his brother, Joe.

Only 21, Joe Dodds, a graduate of Daniel McIntyre Collegiate, was an employee of the Monarch Life Insurance Company, engaged to be wed that June.

A reporter asked Bruce Dodds about the watch. Was it damaged?

“No,” he said. “Watches are supposed to stop when a crash comes, so you can tell what time it was when it happened. But this one never missed a tick.

“I had it in my vest pocket and it was still running when I took it out to look it over.”

It was a gift from his mother, who died six weeks earlier.

Slowly, the Toilers who survived and those who did not returned to Winnipeg by train.

First came the dead. Joe Dodds arrived with Mike Shea on April 2 just past midnight. A crowd waited silently to greet them at the Canadian National depot.

Behind the baggage car was a darkened coach, a Tribune reporter wrote, containing two white coffins. The crowd carried them into the waiting hearse.

Upon his arrival at Union Station a few days later, the Colonel was asked about his experience. “We are most grateful for the way we were treated in Neodesha,” he said. “Residents of the town sent us flowers every day and the mayor called daily to inquire about us.”

The reporter then entered the standard line of questioning. “What was your sensation while falling?”

“It happened so quickly I can’t remember,” he said. “All I know is that I saw the ground rushing up to meet us.”

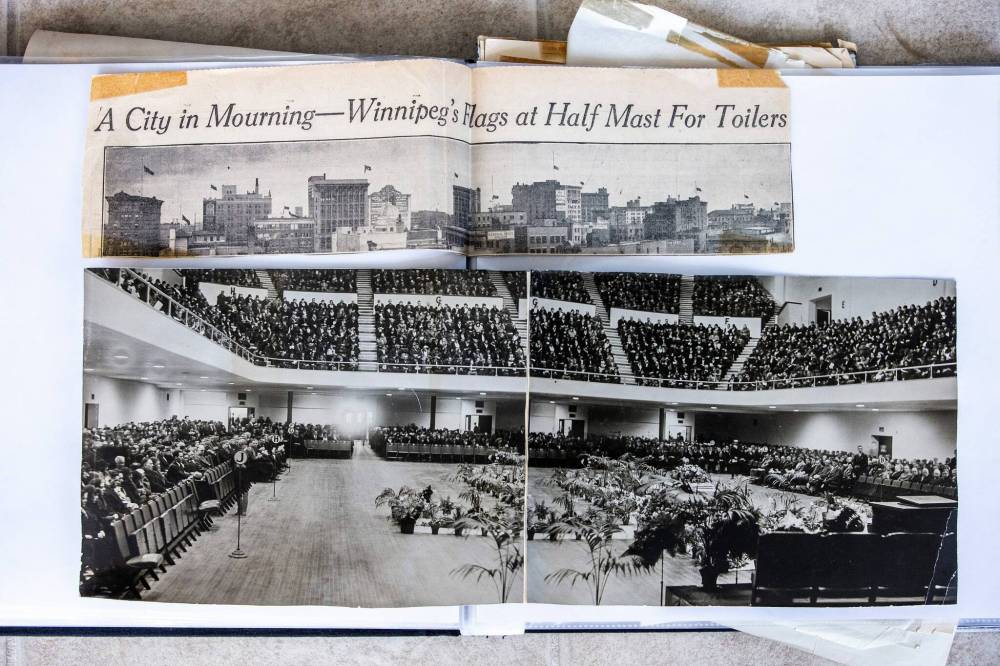

The city was in mourning: the legislative session was suspended, and across downtown Winnipeg, flags were flown at half-mast.

On April 6, the bodies of Joe Dodds and Mike Shea lay in state for three hours in the Winnipeg Auditorium. More than 5,000 visitors arrived to pay their respects. Three days later, Shea was buried at St. Mary’s Cemetery and Dodds’ body was sent on its final train ride, headed for Carlyle, Sask., where the 21-year-old was buried next to his mother.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Residents packed the Winnipeg Auditorium to pay their respects to Joe Dodds and Mike Shea.

A benefit night for the Toilers was held at the Winnipeg Amphitheatre on April 17: it sold out.

Until the survivors got too old to gather, the Toilers crew would reunite every March 31 at the Marlborough Hotel to honour Dodds and Shea, along with the three other casualties.

It was an opportunity to reflect on a miraculous survival that was seen by a few of the members of the team as a form of divine intervention.

A frequent attendee, even after he moved to Victoria, was Lauder Phillips, who walked away from the plane crash unbruised but not unscathed.

His son, Garry, says his father hardly spoke of the tragedy, but it’s clear it made him a more cautious man: he never boarded an airplane again as long as he lived.

The Colonel, who worked the Tribune presses until he was 72, held court over these reunions.

At the 30th reunion, a guest of honour was the baby boy born in the next room over at the Wilson Country Hospital on the day of the crash.

The Colonel attended every celebration until his death from cancer in 1968, one year before the moon landing, which he so often imagined in his beloved science fiction novels, finally happened.

“It’s a shame he did not live to see Armstrong walk on the moon,” says his daughter, Jean Lothian, 90, now living in a seniors’ apartment complex in Tuxedo. At the time of the crash that could have killed her father, Lothian was exactly two months old.

Lothian, like her father, never played basketball, but she loves to watch it. Her favourite team is the NBA’s Toronto Raptors, and her favourite player is their all-star forward Pascal Siakam. “But this young man from Montreal” — she refers to Raptors big man Chris Boucher — “has a tendency to take silly fouls.”

“I love the coach,” she adds of Nick Nurse. “I think he’s fabulous.”

“The Toilers were my dad.”–Jean Lothian, daughter of the Colonel

While a fan of modern basketball, Lothian has a soft spot for the Toilers, even though the club hasn’t played a game since 1945, when a few alumni attempted a comeback.

“The Toilers were my dad,” she says, gently flipping open a scrapbook on the coffee table in her solarium, her stereo playing ragtime piano.

The book was her father’s, stuffed from cover to cover with clippings documenting the swift rise and tragic fall of one of Winnipeg’s greatest athletic clubs.

“It’s amazing,” she says, pointing her finger at a yellowed newsprint picture of the Toilers, standing in front of the Three Hawks plane on the day of the crash.

“How these things last.”

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Much of this story was reported using newspaper clippings collected by Col. A.C. Samson. Also instrumental were the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame’s archivist Andrea Reichert, the Manitoba Basketball Hall of Fame’s Ross Wedlake, and Chris Bauman, Mary Meckley and Ed Truelove of Neodesha, Kan., each of whom shared time and energy helping to gather information.

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.