Vision of survival

Anishinaabe elder’s life calling was forged between worlds, rooted in cultural resilience

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/04/2023 (952 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Elder Robert Greene has been led by vision all his life.

The 69-year-old Anishinaabe Elder-in-Residence at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights is a spiritual man who has learned to trust that his path — one that has been laid out by the Creator’s vision — is exactly where he is meant to be. He is a residential school survivor, a helper and an elder who has spent his entire life helping others.

He was born on Iskatewizaagegan No. 39 Independent First Nation (also known as Shoal Lake No. 39), an Anishinaabe community located just east of the Manitoba-Ontario border near Shoal Lake No. 40. They are the people of the Shallow Water.

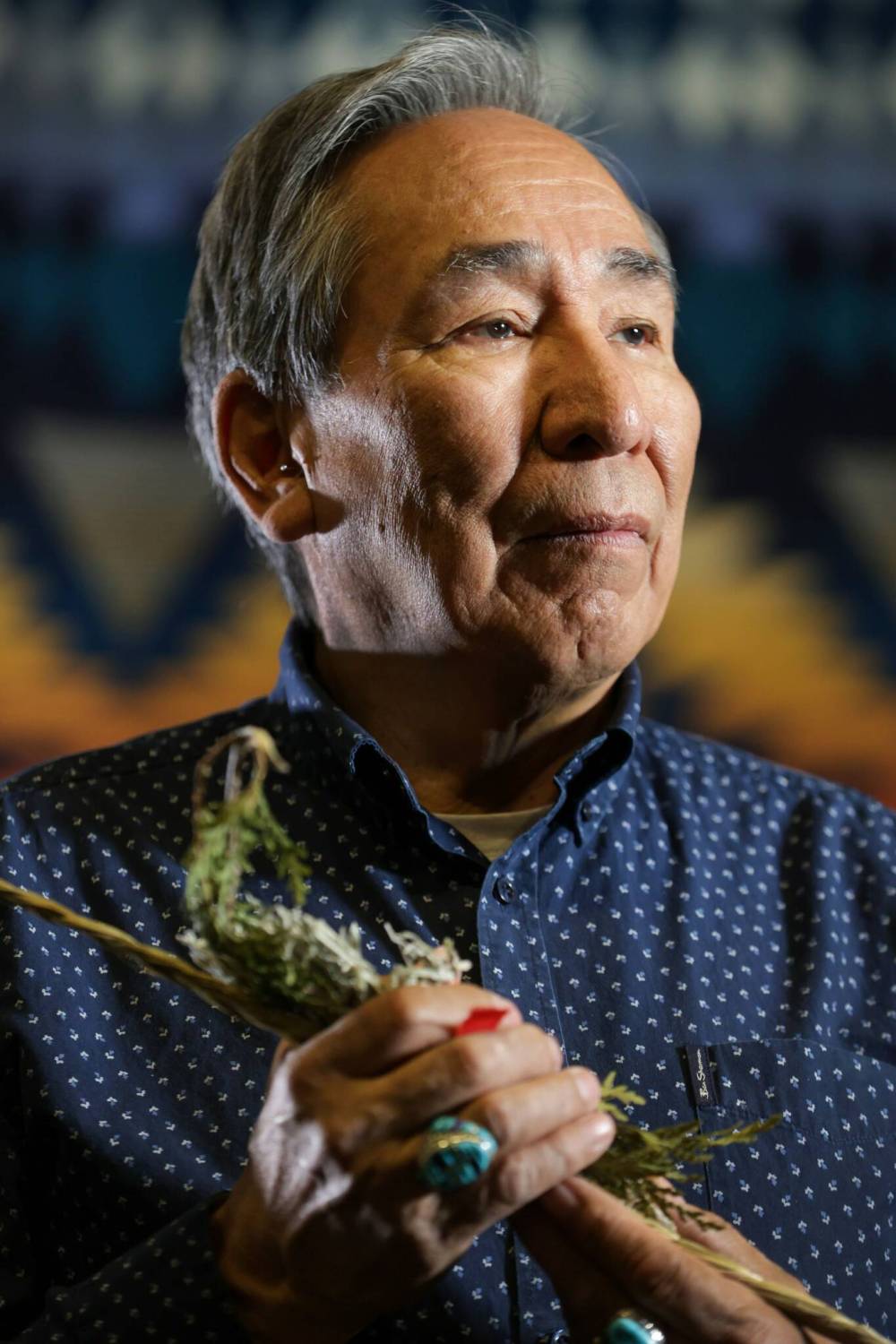

RUTH BONNEVILLE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Robert Greene, whose spirit name is Niizhogabo (Two Standing Man), is Elder-in-Residence at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, where he leads ceremonies and provides an Anishinaabe worldview.

The small, isolated community had no hydro and no road. Greene’s only connection to the outside world was his grandfather’s radio, powered by box-sized batteries.

“I spent the first six months in the moss bag, and up to two years old I was in the cradle board,” he says.

Greene is a soft-spoken man with kind eyes and an easygoing demeanour. When he speaks, it’s in a dialect formed by an Anishinaabe accent from a language that was almost stolen from him as a young boy.

“It was in that process of my upbringing through traditional parenting that I was able to listen first, watch and learn, and then to speak later… find that listening is more important than speaking, because you gain a deeper understanding of what that person is talking about and by listening carefully you find the right words, or the appropriate words to use.”

For the first seven years of his life, Greene spoke only Anishinaabemowin. Nobody in the community called him by his English name.

“They called me by my Indian name, my spirit name. It is Niizhogabo, which means Two Standing Man — I’m named after a spirit that has one foot on the Earth and the other foot on the universe, so I’m standing at two places at once,” he says, adding that he’s from the Moose Clan and second degree Mide’win society.

“My name, my clan, and who I belong to, that’s all part of my identity. That’s all part of who I am as an Anishinaabe man, descended from my grandfathers and great-grandfathers and my grandmothers and great-grandmothers.

“Our way of life was criminalized; it was against the law to do ceremonies. It was against the law to do feasts, powwows, all of that,” he says, adding that the community’s remoteness often shielded it from the scrutiny and near constant surveillance of the Indian Agent and police that other reserves faced. The authorities, he says, usually only came when treaty payments were being made.

Many of the children attended Cecilia Jeffrey Residential School, located just outside the reserve, including Greene’s grandmothers and maternal grandfather. The school operated in that location for 27 years before it was moved to a more centralized location in Kenora.

When he was about seven or eight, Greene attended a day school on the reserve. On the first day of school, when the teacher called out the name Robert Greene during roll call, the little boy didn’t respond.

“Then the teacher came to me and said, ‘You’re Robert Greene,’ and I said ‘Oh, OK,’” he says with a laugh.

“Everybody else, including kids my age, all called me Niizhogabo… We all called each other by our Indian names or spirit names, but at school we had to call ourselves by our English names. We weren’t allowed to speak our language in school.”

When he was 11, Greene, along with his brother and two sisters, was sent to the residential school in Kenora. The boys and girls were immediately split up. Greene remembers only ever seeing his sisters during mealtimes in a mass of other students, all dressed the same, while they ate in the basement dining room.

“The real torture was that as we would file into the dining room, on the way there was this staff dining room; they left the door open deliberately and you would see all that good food on the table, the food that they were going to eat,” Greene explains.

“But when we got to the dining room it was not what we were going to eat — our food wasn’t nutritious. It was mostly just watery soup, maybe a couple of potatoes, or oatmeal, and the skim milk was powdered. Most times it was lumpy because they didn’t stir it enough to dissolve.”

The hunger pangs and thirst were constant and insufferable. The boys quickly learned that if they flushed the communal toilet in their third-floor ward, open among rows and rows of bunk beds, they could drink water that flowed into the bowl.

The children quickly learned how to make beds with meticulous precision, tightly folding in corners — hospital corners, they called them — and adjusting the pillow just right. When the supervisor came around to inspect, he’d flip a coin on the mattress. If it didn’t bounce to a certain height, he’d rip the bed apart and make the student do it again until it was perfect.

“By the end of September everyone knew how to make their beds, even the little ones, otherwise we would get punished as a group punishment.”

It wasn’t just the beds though. Greene says the kids were punished for every little thing, and usually as a group. Throughout the week the supervisors would keep track. If they stood out of line, or if they misbehaved, or if they didn’t listen — each incident would be added to a running list. On Sunday evenings before bedtime, the children would line up, and be called one-by-one by their supervisor to face their punishment — sometimes a strap, sometimes a yardstick.

“We all kept each other in line, looking out for each other in that way,” Greene says.

RUTH BONNEVILLE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Robert Green, Elder-in-Residence at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, with a grandfather/grandmother spirit drum in the reflection room at the museum.

Speaking their language garnered the biggest punishment. If a child was caught, they would be punished in front of everyone, as an example. Sometimes they’d get their mouths washed out with soap or detergent, other times the supervisor would pinch their tongues with pliers.

“They tried as hard as they could for us to lose our language,” he says.

But when the children were alone, away from the sterile building and the prying ears of their wardens, they would speak to one another in their native tongue. They would make each other laugh and tell jokes — all the things they were forbidden to do in the open.

He immersed himself in sports, especially hockey, as a way of coping with the daily abuses he endured.

“We were taught in the residential school never to ask any questions,” Greene says, adding that some of the boys had asked their supervisor a question he couldn’t answer. It made him angry, and the group was punished with a strap.

“We didn’t dare ask any more questions; even though we had all these questions, we never asked them.”

As he got older, Greene and some of the other kids were sent to public schools, returning to the residential school in the evening. They sat in the back of the class because they didn’t want to be noticed.

Greene was struggling academically by the time he reached Grade 8. His principal took notice and asked him if he’d be interested in the boarding home program. Greene said yes, thinking to himself, “Anything to get out of here.”

Soon after he was placed with his boarding parents, a white couple who were both teachers. The pair welcomed Greene into their home and family. After Greene received his report card, consisting of mostly Ds and Fs, his boarding parents started tutoring the boy every night. By the time he was in Grade 9, Greene was back on track and doing well.

The tutoring continued every night and Greene flourished. When he graduated from Grade 13 in Ontario, he did so with honours.

“If it wasn’t for them, I wouldn’t be educated the way I am now,” he says. “I was very thankful for that. They were very kind and very generous. They helped me with a lot of things.”

Greene was accepted into the fine arts program at York University, which he attended for a year. Following that, he moved on to Trent University, but he flunked out and returned home. At the time, there was virtually no support for Indigenous students pursuing post-secondary education.

He worked various jobs at the band office, starting in public works and then moving into a role as a cultural co-ordinator, where he worked with elders and school-age children in the community. He was elected as a band councillor in 1985, serving five terms over 10 years.

By 2005 Greene was unemployed. He tried to find work, but his applications went unanswered.

Then one summer day in June 2006 there was a knock at his front door. It was his nephew.

“He said, ‘My brother wants you to call him,’” Greene says.

When he called, he found out there was a job opening in Crane River First Nation. They were looking for an elder to conduct ceremonies and give teachings — someone who knew the language. Greene said he’d think about it and hung up. No more than 15 minutes later, the phone rang again.

“He said, ‘They gave me money to come and get you,’ and I said, ‘Oh, OK then. You may as well.’”

Greene began working at the Crane River Healing Lodge with inmates from Stony Mountain Penitentiary, many of whom were serving life sentences. Initially he wondered whether he was in over his head, but the work soon became meaningful.

RUTH BONNEVILLE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Born on Iskatewizaagegan No. 39 Independent First Nation (also known as Shoal Lake No. 39), Robert Greene (whose spirit name is Niizhogabo, which means Two Standing Man) spoke only Anishinaabemowin until he was seven years old. Greene is Elder-in-Residence at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

“That was the most wonderful experience I ever had working with those guys,” he says. “I really got to know them well and became friends with them. I helped them, and they helped me…”

After two years, Greene moved on to a role at the Selkirk Mental Health Centre, where he worked as the elder for eight years before moving on again, this time into corrections at Milner Ridge.

In 2008, he was part of an elders’ conference at Bannock Point, where the late Dave Courchene from Sagkeeng First Nation told him about a young woman the group was working with for a new museum being built in Winnipeg — the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Courchene encouraged Greene to talk to the woman.

“First, he (Courchene) goes and talks to her, and then I go and visit her. I didn’t know that it was an interview,” Greene says with a laugh.

During the official opening ceremony in 2014, elder Fred Kelly gave the museum a gift of a drum and a sacred pipe.

“Two years ago, he asked me if I wanted to take care of it,” Greene says of the sacred bundle that hangs on a wall in the museum.

The drum has both a grandfather and a grandmother spirit. At first Greene didn’t want the responsibility, but Kelly was a close friend of his father’s, so he agreed.

Several years earlier, Greene’s father and stepmother brought a bundle to his home. Greene, who was 45 years old at the time, didn’t want to accept it at first.

“Because I knew exactly what it meant,” Greene says.

“You have to be sober, you have to be straight, and all of that… Most of those things I was struggling with at that age, but that’s not the reason I wasn’t accepting that. The reason I wasn’t accepting that is because I knew the amount of work that it takes to carry one of those bundles — to look after it, to do ceremonies with that bundle that was associated with the sweat lodge. My stepmother says, ‘You have to take, the creator knows you’re ready.’”

Now, as the Elder-in-Residence at the CMHR, Greene leads ceremonies, provides cultural support and an Anishinaabe worldview and language, guiding staff at all levels of the organization — from the bistro and boutique to cleaning and security. The work is guided by a circle of other Indigenous elders.

“A lot of our people are hesitant or reluctant to come here because it’s a federal Crown corporation, and they see it as an arm of the federal government — a government that has done a lot of damage to our people, when you look at the history,” he says. “But I’m trying to change that, so they can come in here and be comfortable. And I’m trying to change it so they can come in here and it’ll be a place of healing and a place of truth-telling.”

Greene says no matter if he’s at home or at work, his job doesn’t change. He is still an elder.

“We are a servant to the people that need that help, whether it’s names, whether it’s ceremonies, whether it’s healing, whether it’s purification lodge, like a sweat lodge, or cleansing or counselling, or therapy, anything like that — anything that person needs, we’re there to help.”

shelley.cook@winnipegfreepress.com

Twitter: @ShelleyACook