Fishing for history Researcher working on memorial to honour people lost in Lake Winnipeg

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/04/2023 (982 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Two fishing partners and their dog team, lost through the ice in 1908. A fatal lightning strike to a fishing net in the 1920s. In at least two cases, appendicitis. Shipwrecks. Fires.

These are just a handful of the harrowing stories Heather Hinam has uncovered in her work as a researcher on a memorial that will honour the fisherfolk who have lost their lives to Lake Winnipeg.

The New Iceland Heritage Museum tapped Hinam, a naturalist, artist, interpretive specialist and owner of Second Nature Creative Interpretation, to research the outdoor memorial, which will be located at the museum’s Lake Winnipeg Visitor Centre in Gimli.

So far, Hinam has collected more than 80 people for the memorial, though not all of them have names or dates attached to them yet. She’s trying to go as far back in history as she can, interviewing elders, local historians and, in some cases, family members of victims, as well as combing through newspaper archives and obituaries. The work is meticulous and slow.

It’s not known how many people have died fishing on Lake Winnipeg.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Researcher Heather Hinam is working with the New Iceland Heritage Museum on a memorial that will honour people who lost their lives fishing Lake Winnipeg.

“There’s no one repository, so it’s a lot of piecing together and finding the right search words and knocking on the right doors,” Hinam says.

Julianna Roberts, executive director of the New Iceland Heritage Museum, says the seed for such a memorial was inspired by the Fishermens’ Memorial in Lunenburg, N.S. As it is on the East Coast, fishing is inextricably tied to the history, culture and economy to the communities of Lake Winnipeg — from the First Nations who have been fishing there since time immemorial to the Icelandic settlers who established New Iceland in 1875.

But fishing on Lake Winnipeg is not without its risks; many people have gone out on the lake and never come home. Those losses are keenly felt in a fishing community, which is why Roberts says it’s important to remember and pay tribute to them.

A memorial is also an affecting reminder of the power of the lake.

SUPPLIED Winter fishing (1935) in Hecla from the book Mikley the Magnificent Island.

“My dad was a commercial fisherman and he fished on the lake in the winter, but he always said, ‘The lake is not your friend, because it can turn on you in a heartbeat,’” says Roberts, who grew up in Riverton and is the granddaughter of Icelandic immigrants (on both sides). “So you have to be respectful of it. You have to be respectful of what it can do.”

“I think a lot of people don’t realize that Lake Winnipeg can be very dangerous,” Hinam says. “I mean, it’s enormous.”

Lake Winnipeg is the 11th largest freshwater lake in the world. It’s also relatively shallow, which is what makes it so dangerous.

“The wind can pick up really quickly and without warning, and the waves get much bigger than you would expect for a lake that size, because they whip up really, really fast,” Hinam says.

Most fishing is done in relatively small boats known as yawls, which are particularly vulnerable to waves, Hinam says. “Fisherfolk talk of the Three Sisters. You can see them when you’re sitting on the shore. They’re a succession of three waves that get bigger until the last one can swamp the boat. More than one fisher has been lost to them.”

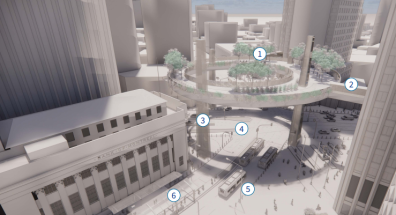

NEW ICELAND HERITAGE MUSEUM A fleet of steamers, including the Suzanne-E, third from left, docked in Gimli in the 1960’s. Nine people out of 10 died on the Suzanne-E when it capsized on Lake Winnipeg in September 1965.

But it’s not just small boats that can run into trouble on the lake. It was a sudden storm that brought down the Suzanne-E, a 70-tonne freighter that capsized on Lake Winnipeg in September 1965. Nine of the 10 people on board died.

Winter fishing, meanwhile, comes with its own dangers — particularly during freeze and thaw. The Icelandic settlers, for example, would have been familiar with fishing on an ocean, less so with fishing on a frozen lake.

“The settlers wouldn’t have known how to fish the lake if it hadn’t been for Indigenous people who taught them,” Hinam says. “There’s quite a lot of collaboration between communities in terms of learning how to fish and learning how to survive on that lake.”

As the commercial fishing industry grew, the lake became busier. It wasn’t unheard of for fishing freighters to carry passengers back in the day.

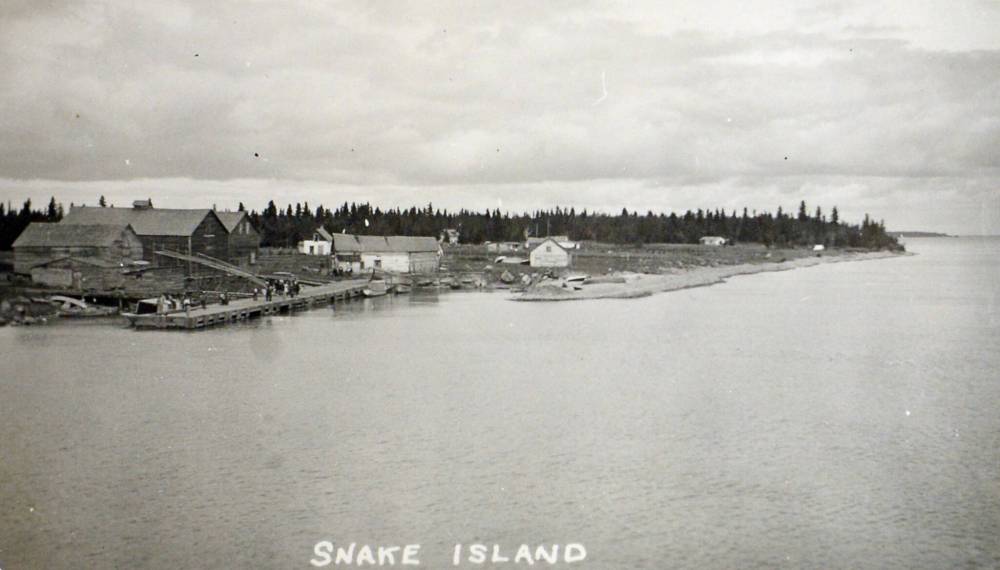

“I love to cast people’s thoughts back to what it was like, even just about the 1950s and earlier, because everything was done by water, everything got moved by water,” Hinam says. “Ships would leave Selkirk, they would go up through the lake. They’d stop at Gimli, they’d stop at all the little fish stations all the way around, because there’s little fish stations everywhere. And people would travel that way.”

GEORGE HARRIS FONDS / MANITOBA ARCHIVES Fishing station at Snake Island, now Matheson Island — at the narrows of Lake Winnipeg.

Some of those people ended up being in the wrong place at the wrong time, such as the lone passenger travelling on the Suzanne-E.

But the memorial is not strictly a historical one; talking to victims’ loved ones is the most difficult piece of this puzzle.

In some cases, a long time has passed, and Hinam says, “It might be somebody’s grandfather, (it) might be somebody’s distant relative. But several people have contacted me with very fresh wounds. And it can be difficult. You have to give them space. I just want to be able to give them the chance to share as they need to, without reducing it down to just a name and a number.

“This is someone’s life and somebody’s loved one. And I take that really seriously, regardless of the time that’s passed.”

Overall, the response to the project has been positive, Hinam says.

SUPPLIED Betty Lou pulling fishing skiff out to their nets at Hecla from the book Mikley the Magnificent Island.

“A lot feel like it’s a long time coming,” she says. “And I think, you know, when someone gets lost to the lake, especially if they’re never found, it can feel like there’s no closure, so I think having this will be really nice for people to have some closure.”

The memorial is not meant to be just Gimil- or Winnipeg Beach-centric, and Hinam and the museum are seeking out contacts from the north basin. “I’m sure there’ve been many, many incidents that we don’t know about,” Hinam says.

The memorial will also be designed in such a way that it can be updated.

“I don’t want anybody to get forgotten,” Hinam says.

People can contact Hinam with information at 204-619-4119 or fisherfolkmemorial@outlook.com.

jen.zoratti@winnipegfreepress.com

Jen Zoratti is a columnist and feature writer working in the Arts & Life department, as well as the author of the weekly newsletter NEXT. A National Newspaper Award finalist for arts and entertainment writing, Jen is a graduate of the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech and was a music writer before joining the Free Press in 2013. Read more about Jen.

Every piece of reporting Jen produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Tuesday, April 25, 2023 8:12 PM CDT: Updates number of people on board Suzanne-E

Updated on Wednesday, April 26, 2023 10:40 AM CDT: Removes reference to Hinam doing design work