Medicine for the Métis soul The first full-scale Indigenous-led opera an act of reconciliation

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/11/2023 (755 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Li Keur has been a long time coming.

“I see this as 150 years overdue,” says Suzanne Steele, a Vancouver-based Métis poet and architect of the first full-scale Indigenous-led opera to be presented on a major Canadian mainstage. “To see yourself onstage, it’s not only nice, it’s necessary.”

Li Keur: Riel’s Heart of the North, presented by the Manitoba Opera, makes its world première at the Centennial Concert Hall Saturday night. The production is the result of a long journey of personal reclamation and reconciliation for many of those involved.

Supplied Vancouver-based Métis librettist Suzanne M. Steele.

Steele began writing the libretto in 2017, but its stage debut was delayed due to the pandemic. Li Keur is a time-travelling work of fiction based on her extensive historic research.

The narrative follows a young woman learning to embrace her Métis heritage through her grandmother’s storytelling. The past plays out in dreamlike vignettes featuring a cast of powerful Indigenous women and Louis Riel, leader of the Red River Resistance and founder of the province of Manitoba.

While Riel is a central figure, Steele wanted to focus on the role of women in preserving culture — an experience often missing from the historic record.

The set mirrors the infinity symbol of the Métis flag, with curved risers decorated in a basket weave and topped with floral beadwork patterns. Scenes of strife and persecution are presented alongside bison brigades, kitchen parties and a boxing match.

“It was written for people to enjoy and to think,” Steele says, adding that she hopes the opera’s theme of joy resonates as much with audiences as its themes of conflict and diaspora.

“We’ve been through all of that but we’re still here — we’re not only still here, we’re doing well.”

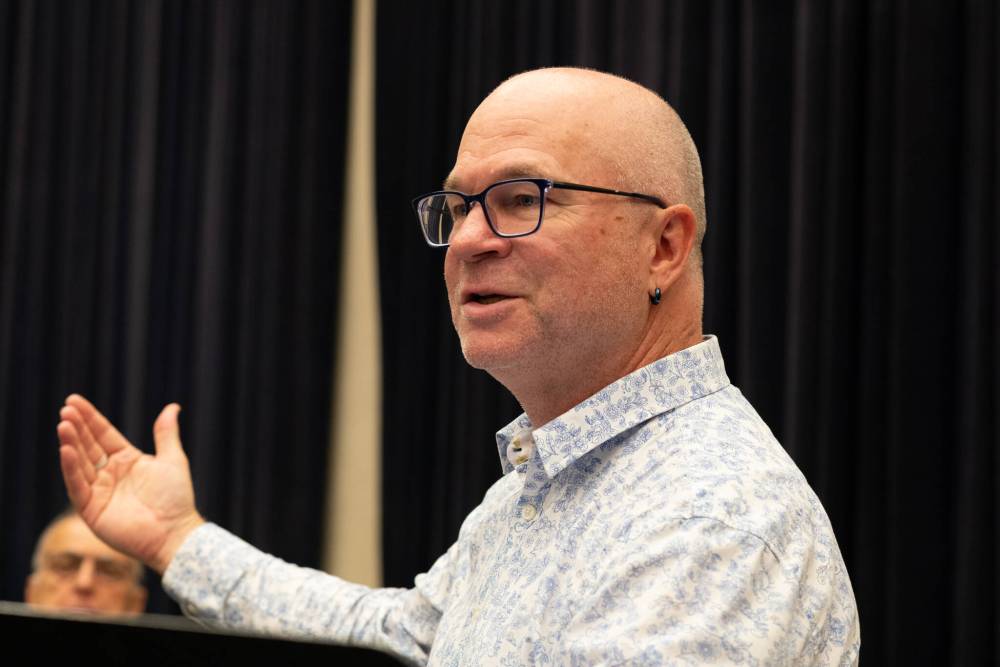

G. Ouskun photo Winnipeg composer Neil Weisensel

Winnipeg composers Alex Kusturok and Neil Weisensel created the music for the opera, which has transformed over the last six years. Originally written in English and French, the script was expanded to include Southern Michif and French-Michif (languages unique to the Métis people) and Anishinaabemowin.

“The music really changed for the better during that process. It’s not a matter of just squeezing the Indigenous languages into what had been written in English; it was taking the whole piece of music apart and re-imagining it,” says Weisensel, who will be conducting the accompanying fiddlers and Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra musicians.

Twelve Indigenous language keepers were hired to assist with translation.

For sisters Donna Beach and Debra Beach Ducharme, the project was a rewarding challenge. The pair spent many evenings and weekends turning English lyrics into Anishinaabemowin, their first language.

“I didn’t realize what we were getting ourselves into,” Beach Ducharme says with a laugh. “It was a lot of work … but we really, really enjoyed the work and I hope this is not going to be the end of opera in Anishinaabemowin.”

Opera Preview

Li Keur: Riel’s Heart of the North

Saturday, 7:30 p.m.

Wednesday, 7 p.m.

Friday, Nov. 24, 7:30 p.m.

Centennial Concert Hall, 555 Main St.

Run time: Approximately 2.5 hours with a 20-minute intermission.

Visit mbopera.ca for tickets

Language revitalization has been a lifelong objective for Beach Ducharme, who is an Anishinaabe knowledge keeper, educator and a member of Lake Manitoba First Nation. Working with opera was a new experience for the sisters; hearing their translations sung for the first time during a rehearsal was a powerful moment.

“It brought tears to our eyes,” Beach Ducharme says. “When people didn’t want to learn our language, we thought, ‘Well, maybe it’s not a good language — maybe there’s a better language.’ But when you hear it sung by opera singers, it’s medicine to our souls and we believe that it’s an incredible opportunity to bring our language and worldview to a larger stage.”

Steele has endeavoured to bring that Indigenous worldview into every aspect of Li Keur, through a culture of collaboration onstage and behind the scenes.

“Classical music is such a hierarchy and we’ve made this into something really collaborative where many voices may speak, not just one,” she says, adding that the working style proved difficult at times. “This is a big conversation we’re having … sometimes it’s not a pleasant conversation and sometimes it’s an awesome conversation.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS From left: Paulette Duguay, Charlene Van Buekenhout, Rebecca Cuddy and Evan Korbut rehearse for the Manitoba Opera performance of Li Keur: Riel’s Heart of the North, opening tonight.

For composer Weisensel, the project has been life-altering.

“It changed the way that I work and the way that I teach, the way I interact with people and my politics,” says the Canadian Mennonite University music professor. “When you talk to elders and they tell you what their life was like … you can’t unhear that. It’s the truth and sometimes it’s very hard to hear, but it was also very hard to have lived. It gives me a new understanding of why we need to work so hard on reconciliation.”

Presenting Li Keur is one piece of the Manitoba Opera’s organizational efforts towards reconciliation with Indigenous communities, which have included education seminars for staff and board members and the creation of an Indigenous advisory council.

“The whole opera sector is trying to be more inclusive to create more opportunities for diverse voices,” says Larry Desrochers, Manitoba Opera’s general director and chief executive officer. “For non-Indigenous audiences, even if they just take a little bit away about the Métis experience or an Indigenous worldview, it will be a huge act of reconciliation.”

The production’s impact

Ahead of Li Keur’s opening night, the Free Press sat down with four cast members to find out how the production has impacted them, personally and professionally.

Ahead of Li Keur’s opening night, the Free Press sat down with four cast members to find out how the production has impacted them, personally and professionally.

Charlene Van Buekenhout is a Winnipeg-based Michif, Belgian and Canadian theatre artist and artistic producer of Echo Theatre.

Paulette Duguay is of French Red River Métis heritage, born and raised in St. Boniface. She is president of l’Union nationale métisse Saint-Joseph du Manitoba and has performed with Théâtre Cercle Molière.

Evan Korbut is an Anishinaabe baritone from Sault Ste. Marie and Garden River First Nation. Recent credits include The Ecstasy of Rita Joe and the Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny.

Rebecca Cuddy is a Métis mezzo-soprano based in Toronto. She has performed in numerous Indigenous and traditional operas, as well as with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, Polaris Prize winner Jeremy Dutcher and cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

For all four, this is their Manitoba Opera debut.

Free Press: Let’s start with everyone introducing and describing your characters as you’ve come to know them.

Charlene Van Buekenhout: My character is Joséphine-Marie. She’s a modern, contemporary person in this opera. She’s off at school doing a graduate program and is trying to write a paper for decolonization class and it’s about self-location … and she can’t get started because she doesn’t want to talk about her Michif background, her Michif identity. She doesn’t want to carry that burden. And that conflict within herself conjures up a visit from her grandmother.

Paulette Duguay: I play her grandmother, Mémère. I’m coming here to nudge her, gently at first, to get interested in our family story and the history of the Métis through different stories and (the rest of the cast) plays them out. So my role, I think, is just the role of every grandmother and that’s transmission of what’s important.

Evan Korbut: I’m singing the roles of Louis Riel and Baptiste Robideau (a buffalo guide who “may or may not be the younger Riel”). I look like the Riel in the textbooks, but there’s a lot more humanity and vulnerability and he’s allowed to make mistakes — and he makes a lot of mistakes.

Some of these (details) are true, some of these things are almost true and some of these things could be true. And that’s how Louis Riel has been characterized over time, depending on who was writing about him. So we’ve come to a confluence of character factors … that I think are probably more real in terms of how he’s portrayed.

Rebecca Cuddy: I’m singing Josette LaGrande and as far as this story is concerned, Josette is very likely Riel’s first love and I think he’s probably hers, too. She has been sold, by her father, to a man she doesn’t want to be with. Josette is a larger representation of Michif women as a whole — very strong, independent, intelligent, talented.

Being controlled by a man is not her destiny, which is also very brave for the time period that this is set in. So she looks to Riel to offer her an escape and they have their journey together.

FP: Rebecca and Evan, you both have previous opera experience. How does this production differ from some of the others you’ve been involved in?

RC: It doesn’t finish with a dead Indigenous woman, that’s a start (referring to a common opera plot trope). And that’s really good for our mental health, as opera singers. It also has a creation story at the beginning, which I’m a huge fan of; it just feels natural.

EK: What’s really struck me is being able to go out into such a massive (cast) and see so many people who look like me. It’s incredible, I’ve never experienced that in opera before. Just seeing so many more Indigenous people out there makes it feel like a community.

RC: What’s also been so exciting is to meet the chorus and the young Métis folks that want to do opera and want to do theatre… It’s just amazing to see those kids in their first show. I didn’t think this was possible 10 years ago, that I would be singing a lead role as a Métis woman playing a Métis woman.

FP: Paulette and Charlene, this is your first opera. What has it been like to be involved in this production?

PD: It’s amazing, it’s overwhelming. You know with 70 people on stage, I found it to be distracting and I’m working so hard on my lines. But it’s amazing — I mean, what an experience. This is the chance of a lifetime. Never in my life did I think I’d be onstage in an opera.

CVB: I have a theatre background — that’s my profession — but opera is so different and it’s been really exciting to learn the form. I love watching and listening to everyone sing and rehearse and seeing those parallels (with theatre). I’m so privileged to be a part of it.

FP: What has it been like to engage with the many different languages that are spoken and sung in this production?

CVB: To see (Southern Michif) words I recognize and hear them in songs that other people are singing is so amazing, because there’s very few speakers; there are less than 50 and that’s being generous. To hear it in song form, it goes right into my body. It’s quite possibly the language that my great-grandmothers spoke and heard and it’s so lovely to hear it blossom in this way.

EK: Indigenous language preservation is decolonization … and it’s a race against time sometimes, with the remaining living speakers to get as much of the language as we can and to preserve. And hearing those things up on a stage, where traditionally a lot of those languages were not allowed, is, to be optimistic, a step forward in the revival of those languages.

RC: Evan and I have been able to do several Indigenous language (operas) and all the others have been in one solid language. And that’s not actually how this land operated. Everybody spoke tons of languages and were able to communicate in many different ways. If they didn’t speak the language, they spoke in sign. I think there’s something so inherently real about the way we move through language in this opera.

And, vocally, these are great languages to sing in, very akin to Italian, very forward and it flows very easily.

PD: This is a good way to reclaim the voices of our ancestors and to give them a voice. For me, that’s the biggest joy of this opera. We’re carrying them, but it’s their story. Finally, we’re able to tell this story on a main stage — it’s about time.

I think Métis people are going to be very ému, very touched. Everybody will recognize something, like “Oh, gosh, I remember pépère would say that” or “That’s an expression mémère used to use.” There will be things that will bring them back to the past. I think it’s such a good, good idea.

FP: What do you hope audiences take away from Li Keur?

EK: I saw my first opera when I was 17 — it was Così fan tutte and it was amazing — but I did not see anybody who looked like me on stage. If I can be that for someone else… that’d make it all worth it. So I’m hoping people, especially Indigenous people, can see themselves and their community reflected on stage and feel like opera is accessible to them — because it should be.

CVB: I hope that it becomes a catalyst for anyone watching to find out more, to find out what is actually true and to open the door to letting go of black-and-white thinking.

RC: I think the audience will experience a lot of joy, but I also feel like there may be a bit of envy here because Mémère has a lot of family history to share. And that’s not actually the case for all of us, right? She’s actually able to bring it into the room and Joséphine-Marie has access to our faces and our bodies and the way we behave. That’s so special and I think that’s going to bring up a lot of emotion for Métis people in the audience, specifically. There’s envy, there’s joy, there’s celebration. And there’s also this passion to keep finding out more.

PD: This nation has been put down so much for so long, that I hope people leave with a sense that it’s OK to be Métis; it really is safe now. The older generation suffered a lot from that lack of identity confidence. So I hope that they come and see and feel some pride and some confidence and some joy. I hope it heals them of all those bad feelings they’ve had — at least a little bit. I want it to be a balm.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Li Keur is momentous for its content and its scale. The production features 70 performers, including 11 principal cast members, six dancers, three onstage musicians and two large adult and children choruses. Much of the cast is Métis or Indigenous and the vast majority have never been involved in an opera production, director Simon Miron among them.

Working with a large group of opera newbies and blending Métis ideology with a traditional European art form has been an exciting learning experience for the longtime local theatre practitioner.

“Historically, the Métis people have been known to … find ways to balance the traditions of their European ancestors versus their Indigenous ancestors and I feel like that’s what we’re doing here,” says Miron, who is two-spirit and francophone Métis. “It’s very apropos that we’re trying to build relationships between these different styles of music and between these different people who haven’t had the opportunity to set foot on a stage of this size before.”

Choreographer Yvonne

Chartrand

Li Keur is a full-circle moment for choreographer Yvonne Chartrand. The first original dance she ever created was inspired by Riel’s wife, Marguerite, and her experience during the Battle of Batoche. Chartrand — whose ancestors hail from St. Laurent — has made a career of preserving and championing Métis culture through traditional jigging and contemporary dance.

“What I’ve always tried to do with my own work is to share our stories from our perspective,” she says, adding that her father, Jules Chartrand, also worked on Li Keur as a Michif translator. “It’s been a profound gift.”

Chartrand created the choreography for and is a performer with the Black Geese of Fate, winged dancers that act as agents of change throughout the opera. The dance elements are inspired by the real-life movements and behaviour of black geese, as well as Li Keur’s layered narrative.

“There’s so much beautiful imagery in the opera that feeds the choreography,” she says. “I feel like I’m in the centre of a whirlwind and the dance is embracing all of it.”

When the curtain rises Saturday, creator Steele is looking forward to a familial homecoming in the heart of the Métis nation.

“I envision this as a big visit, rather than a performance,” she says. “We (as Métis) were cast, like wildflowers into the wind, in the 1870s and we landed all over the continent. But this is our home.”

eva.wasney@winnipegfreepress.com

X: @evawasney

If you value coverage of Manitoba’s arts scene, help us do more.

Your contribution of $10, $25 or more will allow the Free Press to deepen our reporting on theatre, dance, music and galleries while also ensuring the broadest possible audience can access our arts journalism.

BECOME AN ARTS JOURNALISM SUPPORTER

Click here to learn more about the project.

Eva Wasney has been a reporter with the Free Press Arts & Life department since 2019. Read more about Eva.

Every piece of reporting Eva produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, November 17, 2023 6:19 PM CST: Corrects date of opening night.