An exploration of motivations

Celebrated Manitoban author Miriam Toews attempts to unpack why she writes in latest work

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

The question at the core of Miriam Toews’ latest book is one she’s been asked many times. It’s a question with no neat and tidy answer, but one the Manitoba-born, Toronto-based novelist felt compelled to try to unpack: Why do you write?

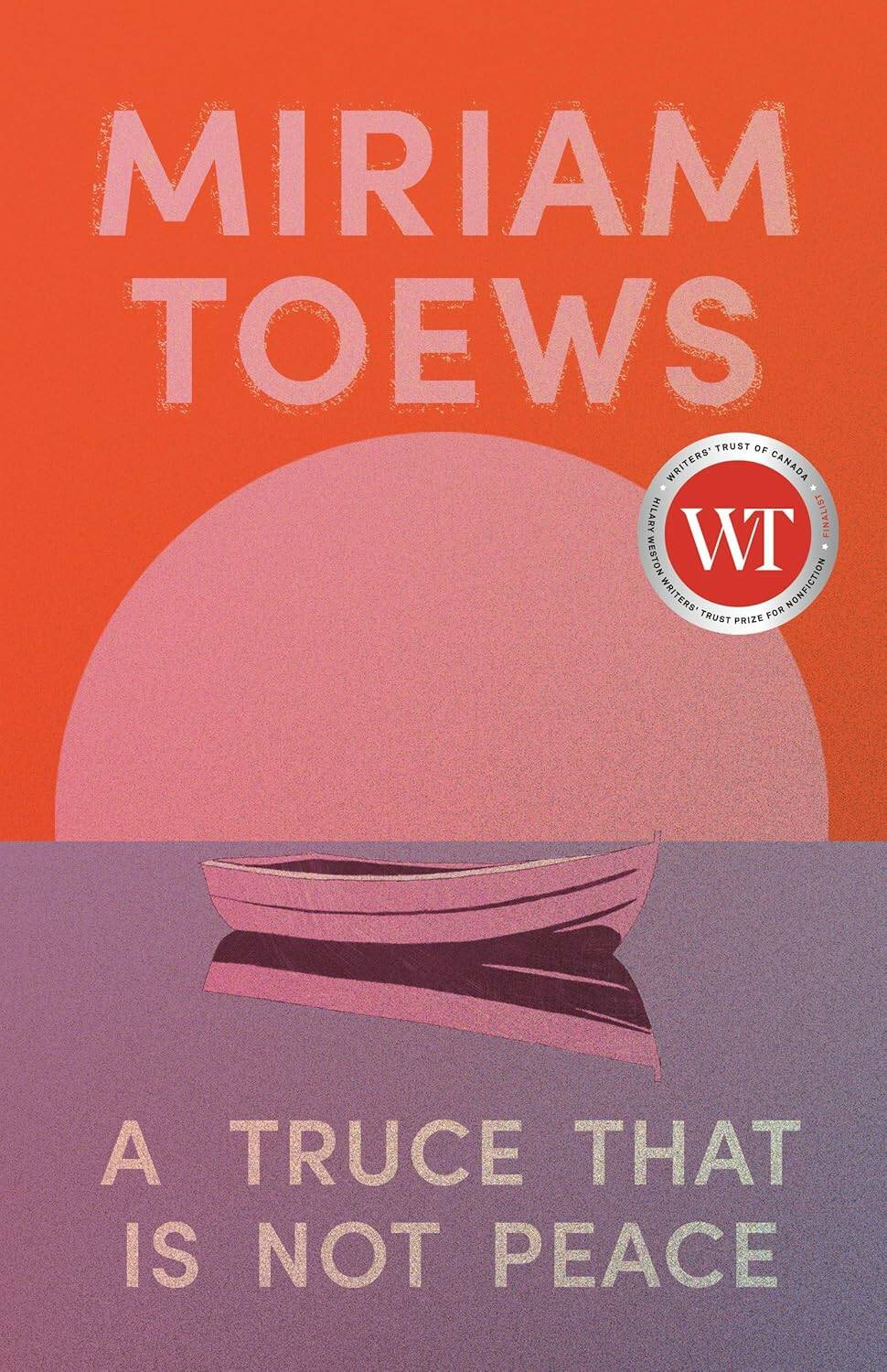

The result is A Truce That Is Not Peace, Toews’ first work of non-fiction since 2000’s Swing Low, a memoir told from her father’s perspective about his life and eventual suicide in 1998.

Mark Boucher photo Miriam Toews says she still feels a sense of embarrassment about her writing, despite her widespread acclaim.

Toews is in Winnipeg Thursday to launch the book at McNally Robinson’s Grant Park location at 7 p.m., where she’ll be joined in conversation by local musician/artist couple Christine Fellows and John Samson Fellows.

The author of All My Puny Sorrows, Fight Night, A Complicated Kindness, Women Talking and other novels has long imbued her fiction with events from her life.

Sorrows, for example, details the mental-health struggles and eventual death by suicide of a pianist, coming after Toews’ sister Marjorie’s suicide in 2010, the day before her 52nd birthday.

Published by Knopf Canada in August, A Truce That Is Not Peace sees Toews, 61, circling around the question of why she writes.

The book reflects on her delightfully chaotic home life in Toronto (she lives with her mother, her daughter and son-in-law and their children), on losing both her father and sister to suicide, on walking the frozen Assiniboine River and on meetings with her ex.

The book’s title stems from an essay by Christian Wiman called The Limit, which is included as Truce’s epigraph.

“That whole quote, the title, just seemed to really nail it in terms of what writing is, what life is, especially a grieving life. A truce — a happy, or somewhat happy, or at least doable truce — I feel may be as good as it gets,” Toews says by phone prior to the Winnipeg stop of her book tour.

Rather than being presented in a linear, tidy narrative, A Truce That Is Not Peace offers fragments of ideas and snapshots in time, with Toews musing on moments in her life that helped shape the writer she is today.

“I hope it sort of represents that chaos of the mind … the kind of fleetingness, the unknowingness, the uncertainty, the agony of a writer’s mind and life — or at least my mind and life,” she says.

“I think there’s some sort of instinct that comes to the fore — and then, in a sense, I’m writing it but there’s something guiding me. I don’t know what it is.”

The core question of the book — why Toews writes — inevitably and unsurprisingly proves unknowable, but Truce does offer both writer and readers a peek behind the curtain at how her novels have come to be.

“I hope it sort of represents that chaos of the mind … the kind of fleetingness, the unknowingness, the uncertainty, the agony of a writer’s mind and life – or at least my mind and life.”

“This book might explain a little bit to me, and maybe to the reader, what I was doing, or attempting to do, with the other books — where stuff came from, the thoughts and feelings, the emotions, experiences, everything — the synthesis of all that. It’s a little bit of a light shone on that,” she says.

Included in Truce are letters written to her sister Marj while Toews was on a European cycling trip with her then-boyfriend in the 1980s. Marj was already struggling with mental-health issues, and had implored Toews to pen letters to her while away.

“She was the instigator, the impetus, the catalyst or whatever you want to call it. At the time it felt like an obligation, a job, an assignment, something I had to do, and I took it seriously. I didn’t want to do it, but when I got into it, I realized I was actually enjoying it, and so in that sense, everything I’ve written was for her,” Toews says.

A Truce That Is Not Peace reflects on Toews’ home life in Toronto, losing both her father and sister to suicide, walking the frozen Assiniboine river and on meetings with her ex.

While her father and sister each chose silence, opting to go months without speaking leading up to their respective suicides, Toews went in the other direction, feeling compelled to write her way through their struggles.

In revisiting those teenage letters to Marj, Toews got a sense of her writerly voice coming to life.

“I could see my younger self struggling to tell a story, to entertain, really — it was writing to entertain her, and to make her laugh, hopefully. And also just the lack of inhibition. I was writing without any notion that those letters would ever be seen by anybody other than her, so there was so much freedom in that, so much intimacy, so much joy,” she says.

Despite Toews’ widespread acclaim and the adoration of legions of readers, she still feels a sense of embarrassment about her writing.

“A lot of writers I talk to absolutely share that feeling — a sense of mortification. If you’re writing with any kind of energy or conviction or intention, you’re automatically exposing yourself, but at the same time, there’s a reason for doing that, which is, ‘Look, these are my thoughts — does anybody else have these thoughts? Am I alone out here?’” she says.

Yet, for Toews, there’s still a feeling of accomplishment, albeit fleeting, in finishing a piece.

“I still have these little twitches like, ‘Oh, I should write.’ And then you go back to the question of, ‘Yeah, but why?’”

“There’s a sense when you think, ‘OK, this is what I wanted to say — I don’t know exactly why or how, but this feels right, this is it. I’m done, finished, the end.’ That’s a really great feeling. The problem is it doesn’t last very long — maybe three or four minutes — and then it’s time to get back to work,” she says, laughing.

Writing, these days, takes a backseat to embracing the chaos of Toews’ house full of family.

“My grandchildren have sort of replaced the chaotic life force of creative energy. All I really want to do is hang out with my grandchildren before they become teenagers and they don’t want to hang out with grandma all day,” she says.

Toews also spends a great deal of time caring for her mother Elvira.

“That’s its own ongoing story as she gets older. There are these stories happening everywhere around me, but in the shape of real human beings, not necessarily characters in my mind.”

Toews describes her care-giving responsibilities as a “beautiful distraction” from her craft.

“But I still have these little twitches like, ‘Oh, I should write.’ And then you go back to the question of, ‘Yeah, but why?’”

ben.sigurdson@freepress.mb.ca

@bensigurdson

Ben Sigurdson

Literary editor, drinks writer

Ben Sigurdson is the Free Press‘s literary editor and drinks writer. He graduated with a master of arts degree in English from the University of Manitoba in 2005, the same year he began writing Uncorked, the weekly Free Press drinks column. He joined the Free Press full time in 2013 as a copy editor before being appointed literary editor in 2014. Read more about Ben.

In addition to providing opinions and analysis on wine and drinks, Ben oversees a team of freelance book reviewers and produces content for the arts and life section, all of which is reviewed by the Free Press’s editing team before being posted online or published in print. It’s part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.