Soil is key to creating distinct flavours for grape growers

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

One of the most compelling components of growing grapes for making wine comes from the ground in which the vines are planted: soil.

There are many different ways grape growers can impact the flavours of a wine — how much to irrigate a vineyard, canopy management to control how much sun hits the fruit and what kind of viticulture is practised all play a role in what ends up in the bottle.

In the winery, producers can choose whether to age in barrels or tanks (and, if the former, whether they’re new or used barrels), how long to let the juice ferment, how long it’s in contact with grape skins and so on, all of which impacts the finished product.

But in viticulture and winemaking, the type of soil in which the vines are growing lays the foundation for almost everything that is to follow. And, generally speaking, the poorer the soil nutrient-wise, the better it is for growing grapes.

Vines grow roots deep into the earth in search of water, and the type of soil they’re planted in can make that search easier or more difficult — and the harder a vine has to work to search for water, the more depth of flavour tends to come through in the fruit.

Dense, nitrogen-rich clay, for example, sees vines having to work hard to reach underground water sources.

Clay is key in regions such as Napa in California, Australia’s Barossa region as well as the island country’s prairie-like Coonawarra region.

The relatively permeable clay in Coonawarra is not unlike the soil found in Prince Edward Island — it’s coppery red and dusty, called “terra rossa” by local winemakers. Cabernet Sauvignon does particularly well in Coonawarra’s terra rossa, with reds produced that are both elegant and powerful.

A soil’s colour can impact the flavours in a wine. Darker soils such as the dense, charcoal-coloured slate found on the steep slopes of Germany’s Mosel region, for example, are warmed by the sun and both absorb and reflect heat, allowing Riesling grapes in that area to flourish.

Volcanic soil is similarly dark but slightly more porous than slate, meaning water drains more easily and vines have to search deeper for water while absorbing heat from the darker earth. This is a hallmark of wines from Sicily, especially those made from Nerello Mascalese red grapes grown on vines surrounding Mt. Etna, an active volcano.

Granite is formed by cooled magma beneath the Earth’s crust — the igneous rock is quick-draining, meaning once roots can permeate the dense rock bed, they must search deep for water. Wines made in granite soils often bring elevated acidity levels — think Beaujolais or Alsace in France, or Portugal’s Dão region.

Gravel is another more porous soil type that reflects heat on to grapes via stones can vary in size from wee pebbles to fairly large rocks.

The picturesque vineyards in Châteauneuf-du-Pape in the southern Rhône Valley are covered in this rocky terrain, as are those in northeast Spain, both of which produce big, dark, dense reds, often Grenache-Garnacha-based and which tend to bring higher alcohol content due to the ripeness of the fruit.

Chalkier limestone runs through wine-producing regions such as France’s Champagne and Burgundy, two areas making arguably some of the world’s finest wines, particularly from Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Made of decomposed sea creatures in areas formerly covered by water, limestone drains well, meaning vines have to send roots deep into the earth for water, while the fruit tends to retain a decent amount of acidity as less sun is reflected on to the fruit.

Whether the soil of a region can impart “minerality” in the flavours of a wine is still a subject of some debate among wine nerds. Perhaps knowing what type of soil in which grapes has a psychological effect on a taster.

Are you really tasting chalky limestone in that white Burgundy, or are you looking for those flavours because you know about where the wine was grown?

Unpacking that is for another time, so for now, another question: If our climate were more amenable to grapes used to make wine, would Manitoba be a viticultural powerhouse?

The short answer is no. Generally speaking, the rich, dark earth that covers most of our province’s agricultural regions is simply too healthy and productive for grapes. (Having said that, kudos to Winnipeg’s Shrugging Doctor Beverage Co., which maintains a few acres of vineyards growing cool-climate grapes in the Pembina Valley, out of which they make wines.)

Manitoba’s pockets of limestone, quartz and gravel would potentially offer intriguing opportunities for growing wine grapes with some character, but in the wider agricultural landscape of the province, it’s unlikely farmers would ever rip out potatoes for Pinot Noir or canola for Cabernet.

Wines of the week

Raimund Prüm 2024 Essence Riesling

Mosel, Germany — $24.99, Liquor Marts and beyond

New to the Manitoba market, this Mosel Riesling is pale straw in colour and offers red apple skin, white peach, pineapple and subtle saline notes (from the slate, perhaps?) on the nose.

It’s light-plus bodied, off-dry and almost spritzy, with lively red apple, peach, lemon candy and flinty flavours showing beautifully with that hint of sweetness, racy acidity and a medium-length finish despite the modest 10.5 per cent alcohol.

Enjoy now or set aside for a couple of years to see how it evolves. 4.5/5

Aveleda 2023 Solos de Granito Alvarinho

Vinho Verde, Portugal — $25.99, Liquor Marts and beyond

Rather than your simple, spritzy and zippy white Vinho Verde blend, this white is made from Alvarinho grapes grown in granite.

It’s medium gold in colour and aromatically offers beautiful floral, peach, red apple and subtle stony notes, with a yeasty component thanks to the stirring of lees (when yeast cells, spent from converting sugar to alcohol, are mixed in from their top layer in with the fermenting juice).

It’s dry, medium-bodied and slightly viscous, with red apple, peach, ripe citrus and almost-honeyed flavours, some underlying stoniness and, at 12.5 per cent alcohol, a medium-length finish.

An elegant, complex and impressive example of northern Portuguese white wine. 4.5/5

Jean-Claude Boisset 2022 Les Ursulines Pinot Noir

Burgundy, France — $34.99, Liquor Marts and beyond

Made from grapes grown on 35- to 40-year-old vines planted in limestone and clay, this red is bright ruby in colour and aromatically brings ripe cherry, earth, plum, white pepper and chalky notes.

It’s dry and light-bodied, balancing ripe red fruit with earthier, slightly vegetal notes that are typical of the grape/region combo, offers medium acidity and very light tannins, while the chalky note and the subtle oak influence (only 12 per cent was aged in new wood, the rest in new barrels) adds depth.

A good point of entry into red Burgundy for the price. 4/5

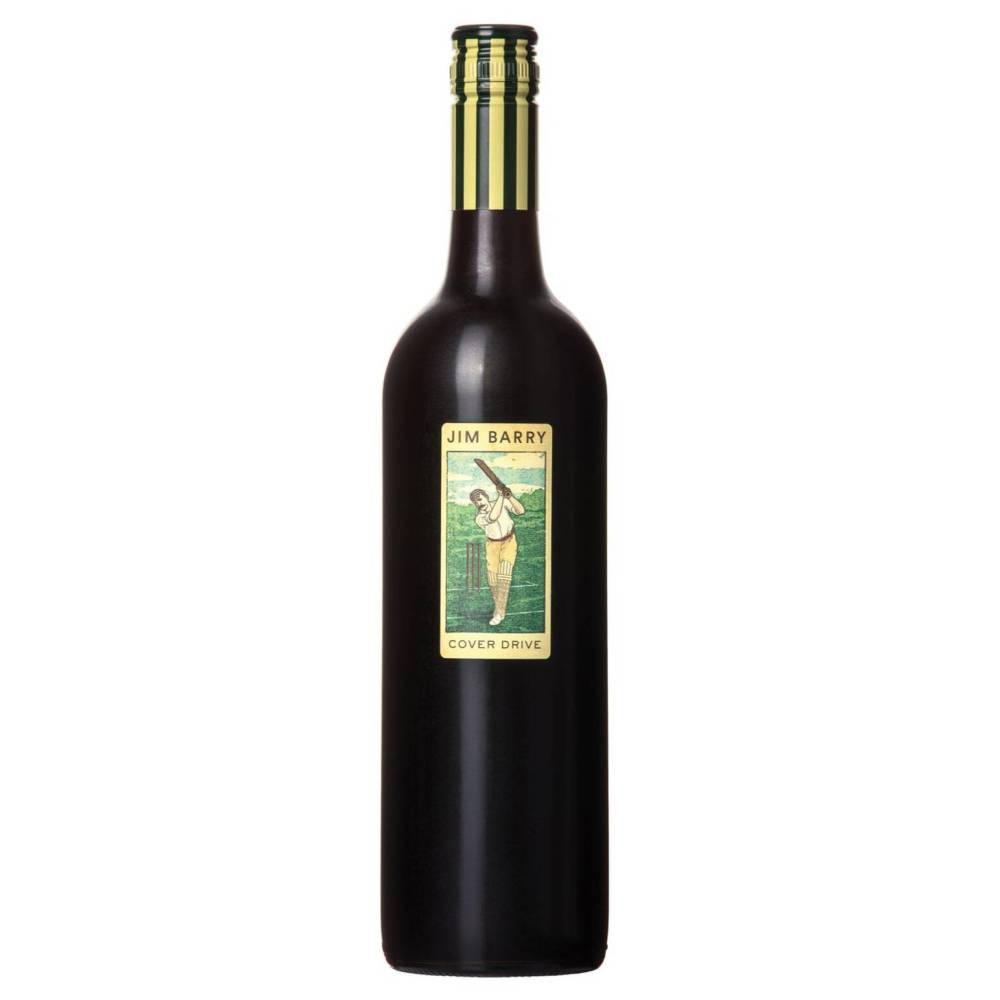

Jim Barry 2021 Cover Drive Cabernet Sauvignon

Coonawarra, Australia — around $22, private wine stores

Inky purple in colour, this estate-grown Coonawarra Cabernet Sauvignon offers bright cassis, blackberry, violet and eucalyptus notes on the nose that are attractive.

It’s a dense, full-bodied and chewy red brimming with blackberry, licorice, anise, white pepper and eucalyptus flavours, underlying earthiness and spice (the latter thanks to 12 months in French oak barrels) lively acidity and moderate tannins and, at 14 per cent alcohol, a long, lingering finish.

Balances power and elegance very nicely — an excellent value red that’s currently only available at The Winehouse. 4.5/5

uncorked@mts.net | @bensigurdson

Ben Sigurdson

Literary editor, drinks writer

Ben Sigurdson is the Free Press‘s literary editor and drinks writer. He graduated with a master of arts degree in English from the University of Manitoba in 2005, the same year he began writing Uncorked, the weekly Free Press drinks column. He joined the Free Press full time in 2013 as a copy editor before being appointed literary editor in 2014. Read more about Ben.

In addition to providing opinions and analysis on wine and drinks, Ben oversees a team of freelance book reviewers and produces content for the arts and life section, all of which is reviewed by the Free Press’s editing team before being posted online or published in print. It’s part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.