Aboriginal art provides good medicine for hospital gallery

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/06/2012 (4892 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When Jackson Beardy was a little boy in Manitoba’s Garden Hill First Nation in the 1940s, he learned the traditional myths and legends of the Oji-Cree people from his grandmother.

At age seven, he was taken away to a culture-negating residential school.

By his 20s, he was lost and troubled. But Beardy found his healing path through art. He went back to his community, re-learned sacred stories from the elders, and began to give them visual form.

“He started to depict these stories in his very bold style,” says curator Leona Herzog.

In 1973, Beardy was a founding member of the Professional Native Indian Artists Incorporation, better known as the Indian Group of Seven. The famous group had a profound influence on aboriginal art being exhibited and valued across Canada.

Beardy, who died in 1984 at age 40, now ranks as an iconic Manitoban artist. He is one of four Manitoba First Nations creators featured in Metamorphosis: A Conversation, a just-opened show at the Buhler Gallery in St. Boniface Hospital.

On display until Sept. 16, it’s the first all-aboriginal show to be mounted at the free, public gallery located just off the hospital’s main lobby.

On Aboriginal Day, June 21, the hospital will be highlighting the show and encouraging First Nations patients, staff and families to enjoy the gallery.

A total of 38 prints, paintings and mixed-media works, dating from the early 1970s to this year, have been assembled for the exhibition. They’re on loan from private and corporate collections, galleries and the artists themselves.

Eddy Cobiness, raised on Manitoba’s Buffalo Point reserve, was a member of the Indian Group of Seven who died in 1996. The other two artists in the show, Jackie Traverse and Linus Woods, are professionals in their 40s who are actively creating and showing.

“This is really an inter-generational show,” says Herzog, who has co-ordinated the exhibition as a master’s student in curatorial practice at the University of Winnipeg. “The work of the forerunners has very much influenced the work of both Jackie and Linus, but they are taking it into their own directions.”

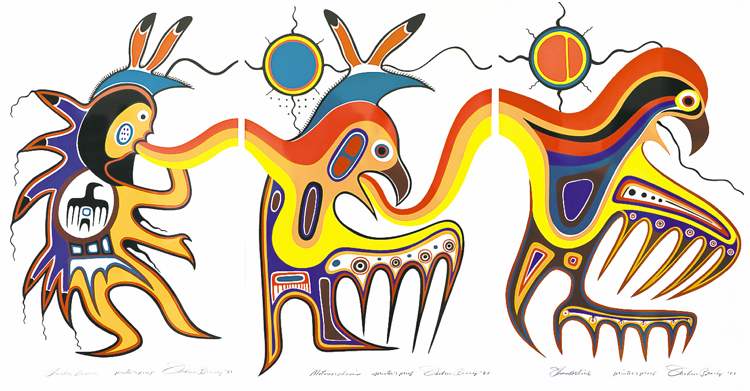

The title Metamorphosis is partly inspired by three Beardy works from 1981 that flow together as a triptych, showing a thunder dancer on the left, a shamanistic transformation from human to spirit animal in the centre, and a thunderbird on the right.

All the artists draw on oral teachings and depict the natural world as interconnected with the spirit world, Herzog says. The gallery’s hospital setting makes it a place of metamorphosis, she notes, since visitors are often experiencing birth, death, profound change or transformative healing.

Both Woods and Traverse were inspired by the opportunity to show in a hospital and created new works for the exhibition, she says. A new Traverse piece called Good Medicine includes bear claws, symbolic of medical healing.

The “conversation” part of the title acknowledges a dialogue between generations, cultures and the works themselves. “The pieces talk to each other,” says Herzog.

Ideas of protection and caregiving, for instance, can be seen in animal families rendered by Beardy and Cobiness, and in Woods’ red stylized eagle spanning the sky and abstract patchwork blanket protecting the Earth in his painting Buffalo Runner.

The works by Cobiness are delicate watercolours of animals such as geese, raccoons, frogs and wolves. The creatures are “X-rayed” to show their inner spiritual dimension, expressed through egg-shaped forms.

Many of Beardy’s silkscreen prints include a wavy ribbon of colour that seems to extend beyond the picture, suggesting life’s infinite flow. “It really is about all of life being connected,” Herzog says.

Woods, from Long Plain First Nation, had a recent solo show called Elk Dreamer’s Dream. At the time, he described his works as “things I paint on my cave wall.” He often integrates symbols of the aboriginal past with visions of the future. Horses figure in many of his large, boldly coloured paintings, as do UFOs and spaceships.

Turtles, ravens and spiral forms recur in the work of Traverse, who comes from Lake St. Martin First Nation but has spent most of her life in Winnipeg. Her recent acrylic/mixed-media work White Buffalo Calf is drawn from the story of White Buffalo Woman, who brought the seven sacred teachings to the Lakota people.

“She has included her own handprint,” says Herzog. “She is marrying the spiritual with the human.”

alison.mayes@freepress.mb.ca