Anishinabe painter brings her distinctive blend of styles and storytelling to North Main

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/07/2013 (4545 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Stories and symbols help us express complex ideas about who we are, what we value, and how we should behave. They come to us passed down through oral tradition, religious teaching, literature and art. Others we pick up along the way: we recount embarrassing family anecdotes, dreams, and things we saw on TV to help frame our experiences, while everyday landmarks become symbolic signposts in the stories we tell about ourselves.

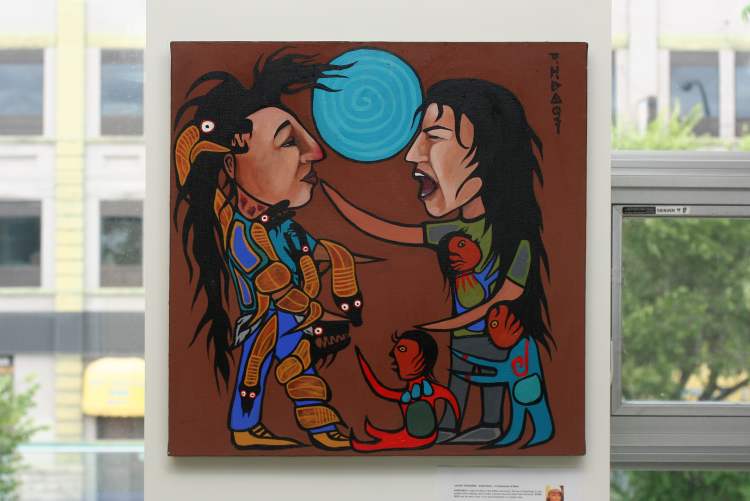

Like any good storyteller, Winnipeg-based Anishinabe painter Jackie Traverse draws on a wide range of sources in Ever Sick, her exhibition at Neechi Niche. Cherished teachings and time-honoured motifs intersect with wry caricatures of contemporary urban life, while events from the artist’s childhood (both real and imagined) become the basis for personal mythology.

Known for painting in the bold, abstracted Woodlands style popularized by artists like Norval Morrisseau and Daphne Odjig, Traverse cleverly reworks its signature snaking black outlines and saturated palette, teasing out parallels with graffiti art and cartoon illustration. The result is an engaging pastiche of styles that ideally suits her varied subjects, direct approach and easy humour.

With the economy of single-panel comic trips, the paintings in the series Seven illustrate the Anishinabe Seven Teachings (wisdom, humility, bravery, etc.) as they go disastrously, hilariously unheeded by a put-upon cast of characters. A ragged-looking father stumbles home on Sunday, having blown his paycheque Saturday; a deluded old coot hotly pursues a visibly distressed beaver and Traverse’s boyfriend faces difficult questions in the areas of honesty and love. (“No, honestly. Do these jeans make by butt look big?”)

Childhood Memories presents a comical series of white lies and misunderstandings, though the humour of the situations often belies more complicated realities. In one painting, a bat carries toddler-Traverse off by the hair because she didn’t wear her tuque — just like her mother warned — while another looks back on a particularly regrettable perm.

Others apply a light touch to thornier subjects: Uncle Rudy recalls the time Traverse’s cat had kittens, which the family gave away without telling her. When she asked about them, her aunt explained: “Children’s Aid took them away and put them in a foster home.” Having already seen siblings removed, the story seemed plausible enough.

The Baby Gat series also considers how childhood innocence fares under difficult circumstances. The 16 small paintings show Cabbage Patch cartoon infants in gang attire, some brandishing firearms, others clutching bullet wounds. Unlike other works in the show that strike a more persuasive balance between humour and seriousness, I’ll confess these seemed at once flippant and heavy-handed. At the same time, several refer to specific events in the lives of Traverse and her family, whereas my idea of “gang activity” generally involves synchronized dancing, so, really, who am I to talk?

Symbolism and storytelling rely on shared experience and strengthening bonds of mutual understanding among members of a community. Traverse’s inventive fusion of artistic traditions and her frank, funny and heartfelt treatment of her own experiences would be compelling under any circumstances, but it’s important the work is being shown across the street from the Yale and Northern hotels, whose signs loom large in one painting, down the hall from the Neechi Niche’s store, which offers books and art supplies to up-and-coming storytellers. It’s where Ever Sick is likely to have the strongest, most lasting impact.

Steven Leyden Cochrane is a Winnipeg-based artist, writer and educator.

History

Updated on Thursday, July 25, 2013 9:11 AM CDT: replaces photo