Writing her way forward

Graphic memoir builds fraught family archive on concessions, limitations

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/11/2024 (379 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

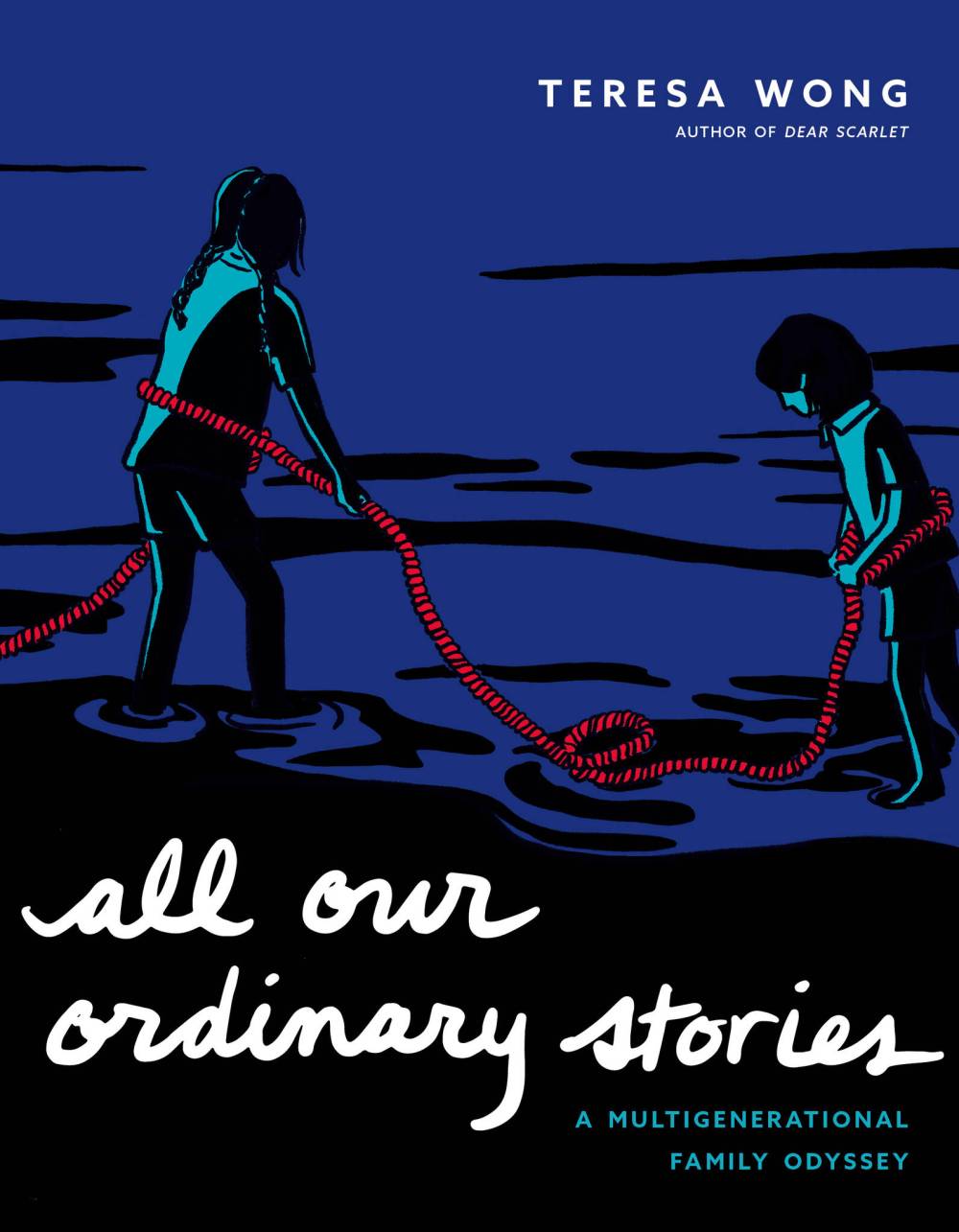

In her sophomore graphic memoir All Our Ordinary Stories: A Multigenerational Family Odyssey, second-gen Canadian cartoonist Teresa Wong pieces together the history of her Chinese immigrant parents. With striking black-and-white sketches and simple prose, Wong documents the painstaking process of this assemblage, from encountering incomplete immigration documents to the elder Wongs’ reticence to discuss the events of their youth. As the author uncovers these memories and traumas, she reflects on how they have shaped her family, with sequential art that deftly reveals and bridges the lack of shared language and familial closeness.

As memoir writing and family history are often closely intertwined, Wong cheekily opens her story with a viral tweet that inquires: “are you the eldest daughter of an immigrant household or are you normal,” setting the tone for a candid look at her family’s narrative. The book’s events are prompted by the aftermath of a stroke suffered by Wong’s mother, and the rift that results from a frustrating series of conversations about her recovery. “After that night, we stopped talking about… anything that mattered at all.”

Feeling immense guilt about her lack of Cantonese fluency, Wong uses visual language to reflect the resulting distance between her and her mother; one panel containing each of them are positioned in the top left and bottom right corners of the page, with the vastness of the blank white space in between them speaking to their isolation.

Kaitlin Moerman photo

Teresa Wong takes care to present her parents as people with full lives.

Throughout the book, Wong cleverly deploys the presence (and absence) of both language and physical space to illustrate the degree of closeness between herself and her family. Her father, having grown up in China with an absent father, also plans to move back there alone, to “be free” of his own family, which the author first overhears out of an open window. They are physically separated in a way that does not afford them a dialogue.

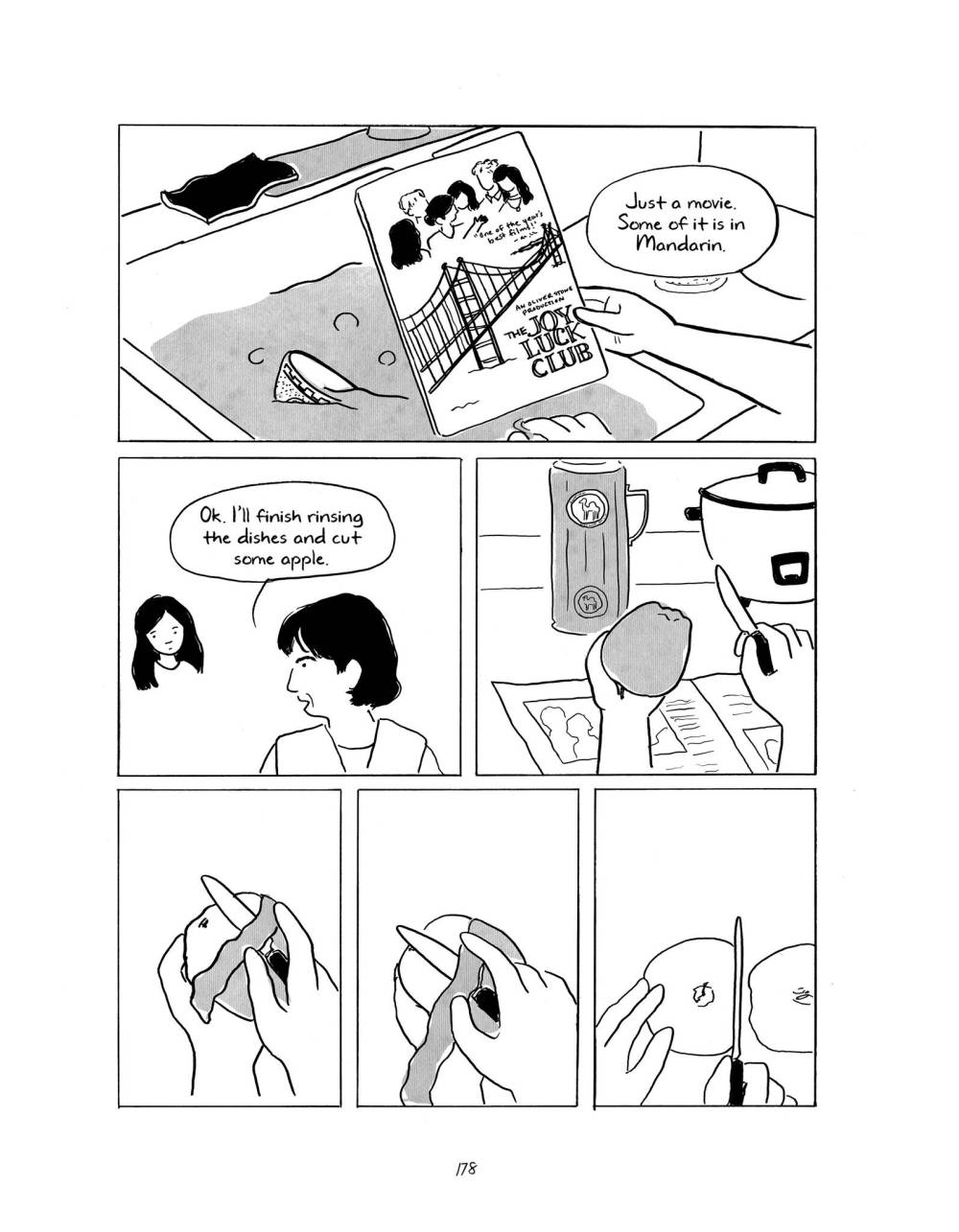

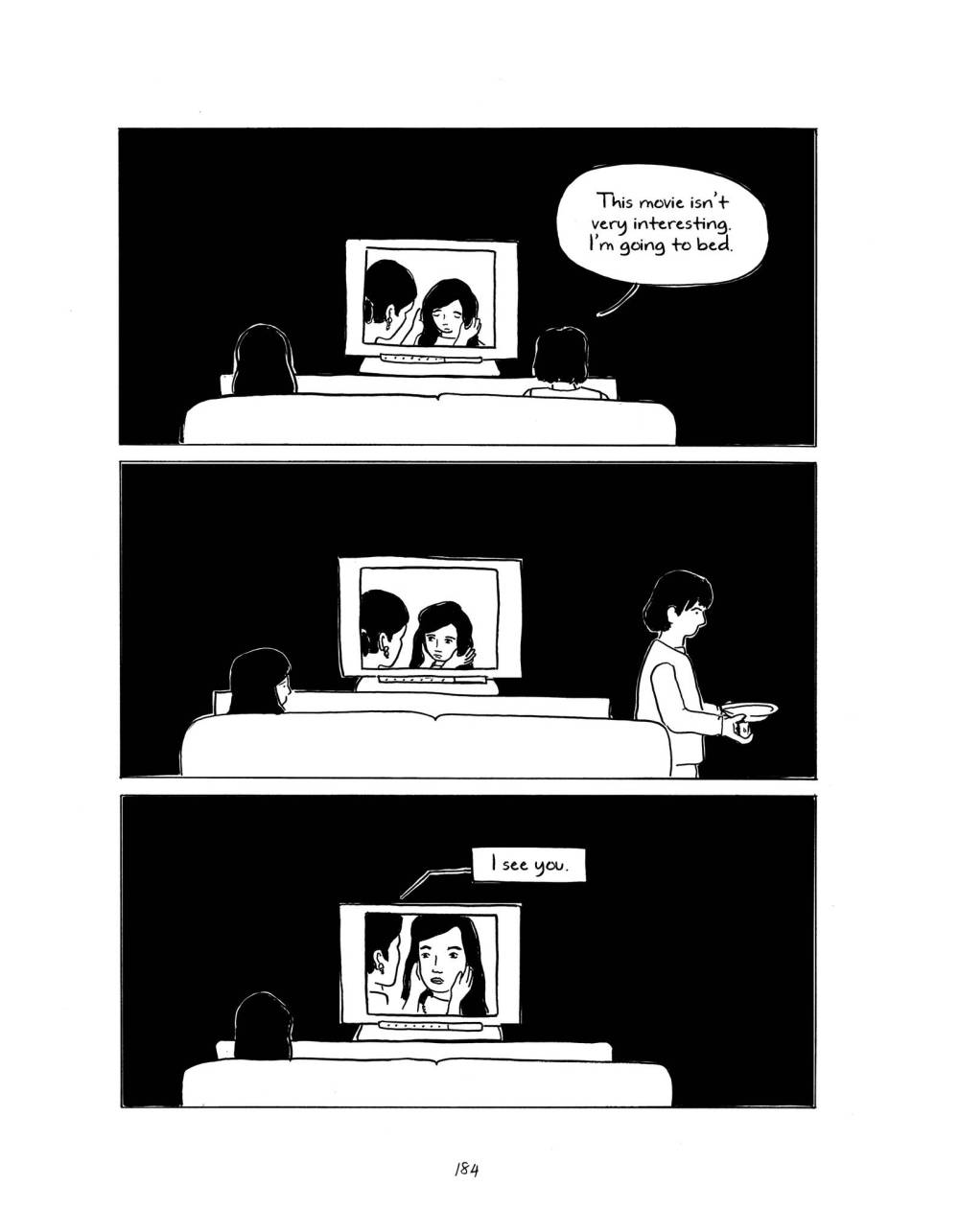

A later scene depicts mother and daughter watching The Joy Luck Club on the same couch, again isolated in separate panels. “It was the first time I had really seen myself in a movie,” Wong writes.

But as she is moved by a particularly emotional scene in which a character is finally validated by her mother, Wong’s own mother is disinterested, and walks away. This exchange is particularly heartbreaking for the author, given a childhood spent immersed in Western media, hoping to recreate the connections and heart-to-heart moments present in many a tv sitcom with her own parents.

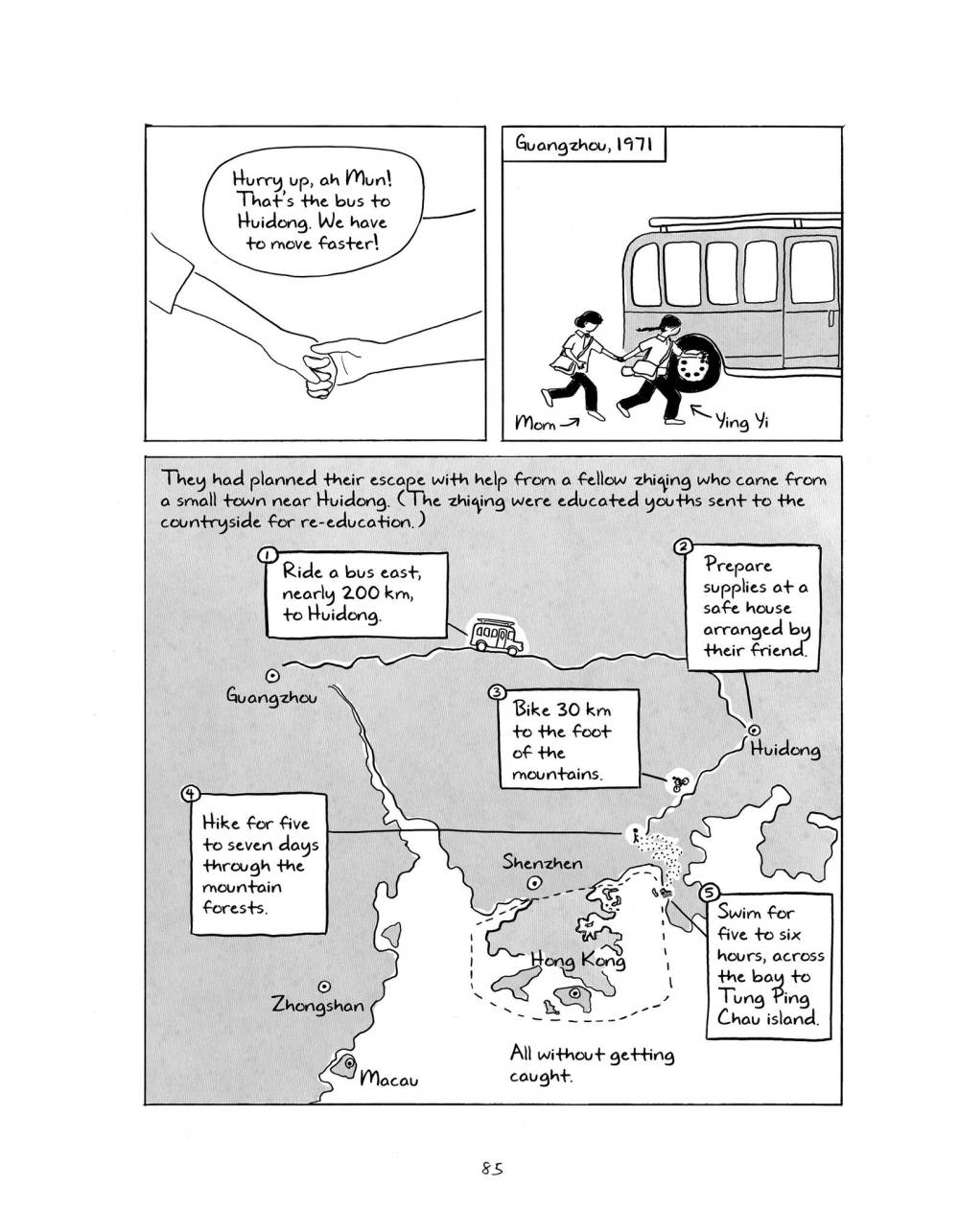

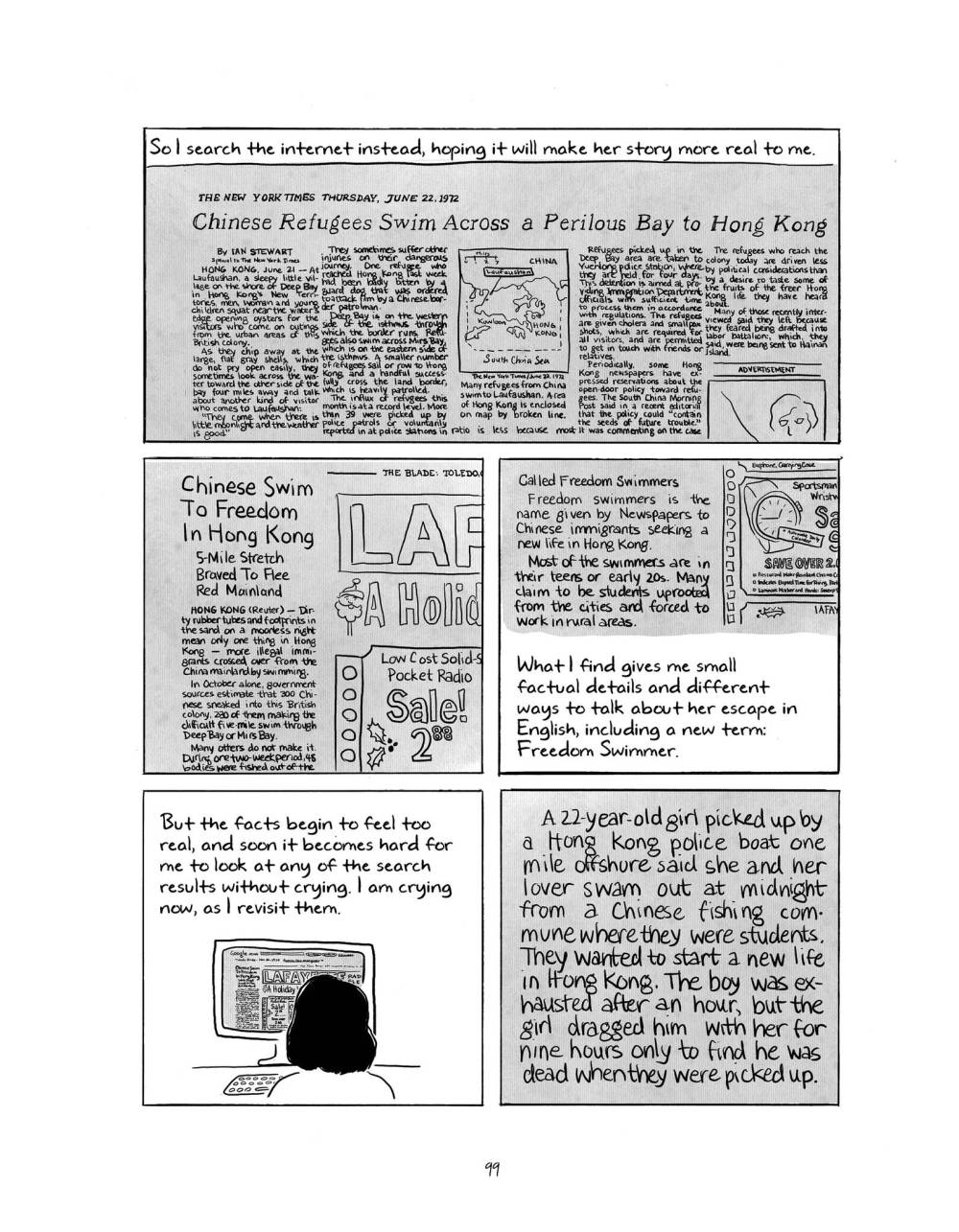

Although quitting Saturday morning Chinese school had felt like freedom at the time, as an adult the author is now unable to fully parse the little information she can find about her family’s past. Wong later uses online articles to fill in the gaps concerning her parents’ separate escapes to Hong Kong during the Chinese Revolution, as well as to find information about her paternal great-grandfather, affording the reader important details about the Canadian government’s treatment of Chinese immigrants. These carefully recreated maps and articles, as well as harrowing firsthand accounts, brilliantly translate the physical and emotional vastness of the risks involved, and the lingering traumas that continue to permeate the Wong family years later.

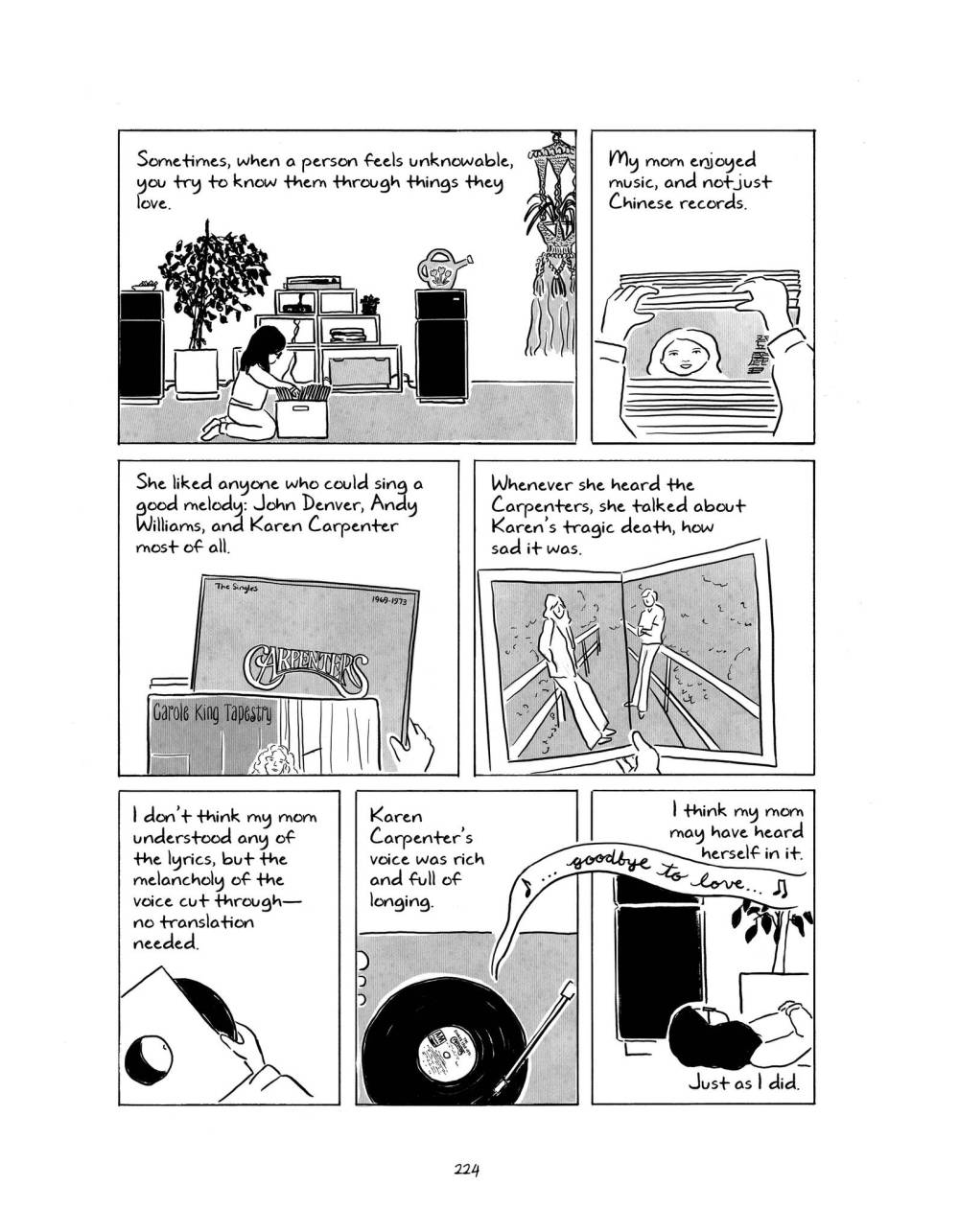

But the author also takes care to mention that “a person is more than their hardships,” presenting her parents as two people with full lives and their own personalities and interests. She especially connects with her mother’s vinyl records and her father’s paintings, musing on how her lineage is visible in his own “impulse to make art out of his experience.”

All Our Ordinary Stories

In producing a kind of family archive built on concessions and limitations, Wong, herself a new mother at the time, also admits that she might never fully know her parents’ story, but can ensure that her children will know hers.

Stories, ordinary or not, all require a language to tell them, and Wong’s skilled, vivid use of the comics medium to “write (her) own way forward” will resonate with readers.

Nyala Ali writes about race and gender in contemporary narratives.

Wong uses online articles and maps to fill in the gaps concerning her parents’ separate escapes to Hong Kong during the Chinese Revolution.

With black-and-white sketches and simple prose, Wong documents the painstaking process of assembling her family history.

Wong depicts watching The Joy Luck Club with her mother, before her mother grows disinterested and leaves.

Wong connects with her mother’s vinyl records and her father’s paintings.