Life processes

Celebrated Manitoba glass artist works through fears of unchecked technology in evocative installation

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/01/2017 (3184 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Ione Thorkelsson is hardly alone in worrying about the pace of biotechnological research, though I don’t exactly share those fears myself. To Thorkelsson’s dismay, neither did her friends.

Back in 2010, the Roseisle resident and Governor General’s Award-winning glass artist was rattled by news that the American biochemist and entrepreneur Craig Venter’s lab had produced what they were calling “synthetic life.” The team had “transfected” a living cell with a modified bacterial genome, producing a viable new organism, Mycoplasma laboratorium.

Similarly engineered strains could have applications in everything from medicine to energy production and carbon capture, but for Thorkelsson the announcement had shaken her “innate understanding of what was fundamental and unchanging in the natural world.” What’s worse, others didn’t seem to feel the same. “Where was the debate? Where was the tell-tale (sic) involuntary shudder?”

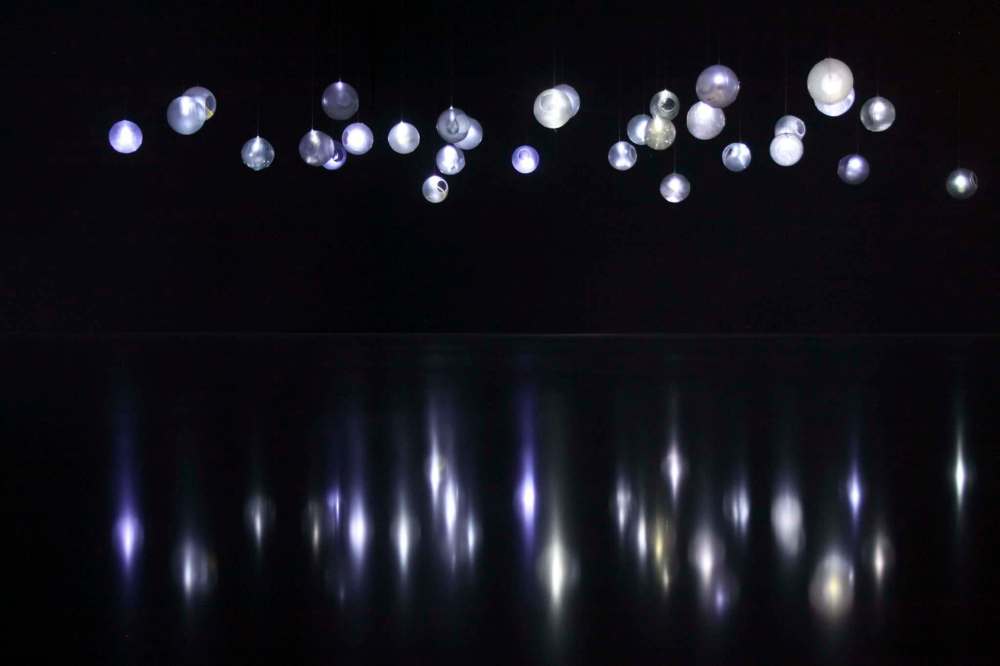

A brooding installation of blown- and cast-glass forms, natural materials, faintly glowing LEDs and fibre-optic strands, Synthia’s Closet opened last week at the University of Manitoba’s School of Art Gallery. The work came out of Thorkelsson’s efforts to sit with her misgivings, to understand her fears and give them form. I underwent something similar in my own shifting response to the work.

I approached with knee-jerk skepticism. Having grown up the child of a geneticist and a climate researcher in the American Bible Belt, I have no patience for anti-scientific scaremongering. Her fixation on Venter — a controversial public figure, to be fair — seemed to me especially troubling. Media clippings and a screenshot of a fake Facebook profile for “Synthia Venter” hang outside the gallery door, reminding me uncomfortably of the vilification and intimidation tactics favoured by the anti-vaccine, anti-choice and climate-change-denial crowds.

But even if I don’t share Thorkelsson’s specific fears, walking into the all but pitch-dark gallery I felt them for a moment, or something similar. The sliding doors close and you’re suddenly without bearing. Scale and distance are at first impossible to gauge, and Thorkelsson’s sculptures seem to hang in empty space. The ambience is otherworldly, the effect alluring and unsettling in equal measure.

Up close, each sphere is different, the glass uniquely textured, each sheltering a fragile cluster of electric lights, small bones, feathers, twigs, tangles of monofilament and scraps of reflective Mylar. The juxtaposition of fine craft, natural material and electronics is a familiar strategy for illustrating technological encroachment, but it’s effective in this setting. It’s tempting to imagine what each “cell” might have the potential to become, which might be cause for wonderment or alarm, depending on your outlook.

Mistrust of people’s motives notwithstanding, I guess I side with wonder. Thorkelsson’s installation creates space to reflect on the complexity, precariousness and sheer improbability of life processes. Venter’s research does the same for me, but Synthia’s Closet does produce that telltale shudder Thorkelsson was looking for.

A public reception is scheduled for Feb. 2, followed by a free artist talk, but I recommend also visiting on a quiet weekday, when you’re most likely to experience the work one-on-one.

Steven Leyden Cochrane is a Winnipeg-based artist, writer and educator.