Invisible no more

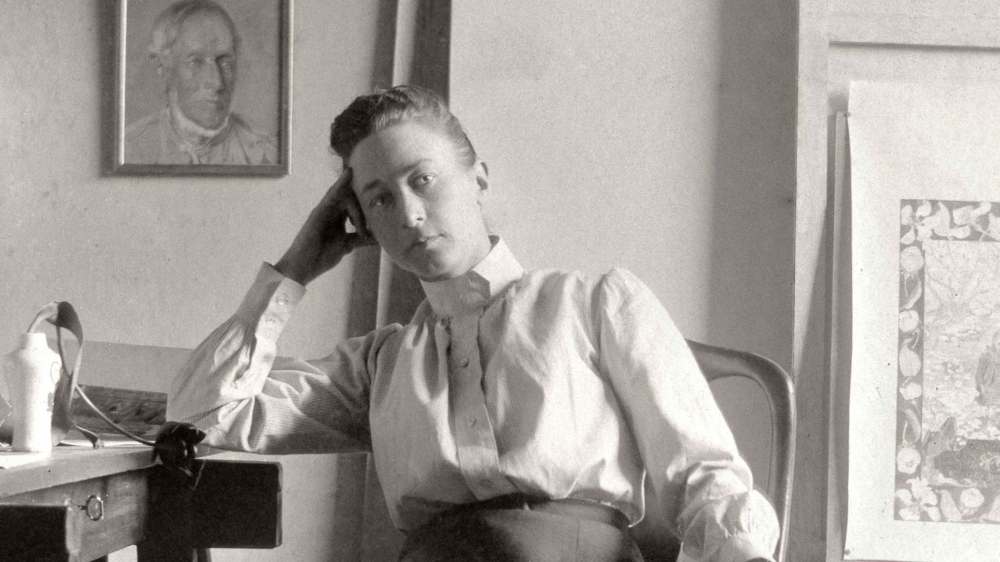

Scandalously overlooked pioneer of modern abstract art gets recognition she deserves

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/05/2020 (1995 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Back in 1989, a group of feminist artists called the Guerrilla Girls ran a subversive campaign asking the question: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?”

The poster pointed out that less than five per cent of the artists in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s modern art section were women, but 85 per cent of the nudes were female.

Museums and galleries have since stepped up efforts to create more gender equilibrium. But this documentary, Beyond the Visible: Hilma af Klint, indicates there is still some distance to go, with its portrait of the female artist who invented modern abstract art as we know it.

This history runs counter to the facts laid down by New York’s Museum of Modern Art, apparently the arbiter of that niche of art history. But director Halina Dyrschka makes a solid case that Swedish artist Hilma af Klint’s work not only preceded the likes of Wassily Kandinsky or Piet Mondrian (or Andy Warhol, for that matter), it might have influenced those male artists as well. But she was never given her due while she was alive (she died in 1944) because, even in the most free-thinking of media, the gatekeepers of criticism and exhibition were predominantly male.

That outrage fuels the film, just as it presumably fuelled the filmmaker. But the doc wouldn’t hold up if af Klint’s body of work didn’t warrant closer examination.

And as a matter of fact, the work is remarkable, especially the huge 10-foot paintings that reflected af Klint’s preternaturally cosmic world view, informed by the pioneering work of scientists and theorists — including Albert Einstein — that she studied as the 19th century turned to the 20th.

Af Klint had the good fortune of being born into an aristocratic family of Swedish naval officers who specialized in creating maps and charts. (Dyrschka slyly implies that background had its own influence on af Klint’s style, at least her penchant for dotted lines.) Her father supported her artistic aspirations. Since she was unmarried, and showed no inclination to get hitched, it was reasoned that she would be able to support herself with her early artistic efforts as a naturalist painter and illustrator.

But, as the title suggests, af Klint was seduced by the ineffable stuff that was starting to be discussed — the atom, light waves, energy. And she admirably set about the task of capturing in art the phenomena that could only be portrayed in the abstract.

One of the convenient reasons to ignore her work was that af Klint was a spiritualist, who joined a group of women and some men (including August Strindberg) who regularly held seances. She was also a theosophist, and her consideration that all religions are one religion is very much a part of her work. It was easy to suggests a spiritualist artist should not be taken seriously, but only as it was a woman. (No one held that against William Blake, one critic offers.)

Director Dyrschka presents a lot of that work in an occasionally overwhelming succession of shots of canvases, notebooks and af Klint ephemera. Fortunately, she also features a couple of fiery advocates of her work, including curator Iris Müller-Westermann, who organized a 2013 af Klint retrospective at Stockholm’s Museum of Modern Art, and American artist Josiah McElheny, who may be seen as an outright fan.

That enthusiasm presumably may be credited to cinematographers Luana Knipfer and Alicja Pahl, who not only lovingly present af Klint’s pictures, they employ startling natural images that reflect af Klint’s unique way of seeing.

randall.king@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @FreepKing

In a way, Randall King was born into the entertainment beat.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, May 23, 2020 1:03 AM CDT: Adds photos