Kvetcher back to tell us how not to be a shmuck

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/09/2009 (5845 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

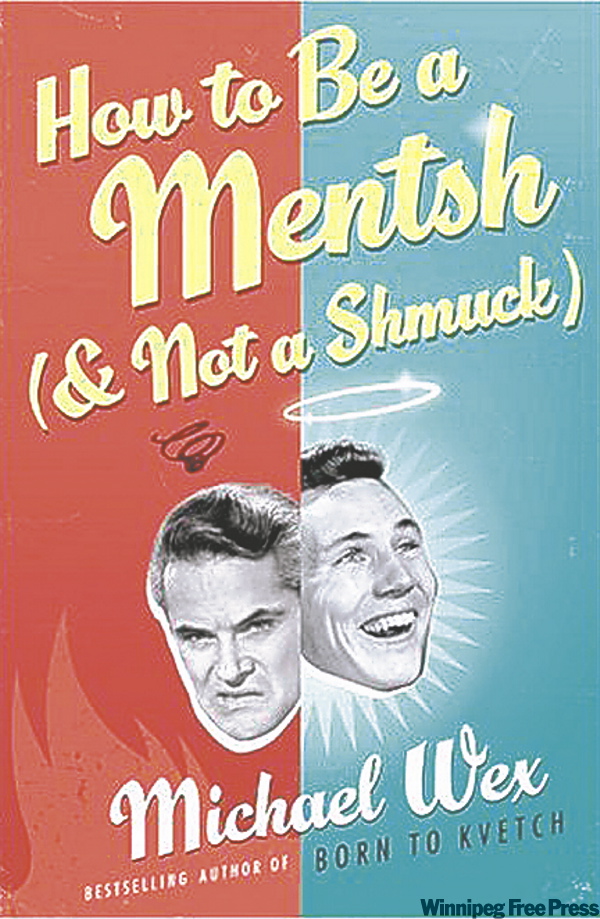

How to Be a Mentsh

(And Not a Shmuck)

By Michael Wex

Knopf Canada, 208 pages, $30

Don’t approach this book like a shmuck.

If you have heard of Toronto-based Michael Wex’s bestseller Born to Kvetch but not read what is marketed as a humour book, you may well be disappointed when his followup, How to Be a Mentsh (And Not a Shmuck), does not quite turn out to be the ribald romp insinuated by its table of contents.

After all, what is a shmuck to make of titles such as Extending the Shmuck and How to Do it Like a Mentsh?

At the very least a shmuck would expect a hilarious reading experience that would cause even a Flat German Mennonite, sombre as a cabinet minister during a recession, to laugh himself until his belly kvetched.

The introductory chapter, Don’t Be a Shmuck, actually reads like a "how to" book, of the inspirational variety at that, almost like a televangelist’s pitch complete with a Jesus-on-Facebook anecdote.

A shmuck almost stops reading at this point, except that Wex drops a few F-sharps into his "how-to" prose and that’s different from what you might hear from Jack van Impe.

Chapter One, What’s a Shmuck?, starts to bring it by that this book is about words. And, yes, Wex writes about the meaning of shmuck that you learned in the schoolyard or from a cousin who had a sister with a Jewish boyfriend.

And the book does nudge itself toward being funny as Wex talks about the "dirty" meanings of shmuck with his analysis of variations such as shmekele and shtekele and shtok and shtekl.

A Flat German Mennonite from southern Manitoba might well start to wonder how a Jew born in the shtetl of Lethbridge knows so much Plautdietsch, not to mention why he gives a word which in Plautdietsch means "pretty" and "well-behaved" such a crude meaning.

To be schmuck in Plautdietsch is a good thing, whereas Wex’s shmuck covers pretty well all possible negative human behaviour while mentsh embodies all things exemplary.

Wex makes sure the reader doesn’t confuse his Yiddish mentsh with the German mensch and he emphasizes in a number of passages that Yiddish is not just another dialect of German.

He goes so far as to claim that only in Yiddish has this word mensch evolved from the German meaning of man into mentsh meaning a "person of moral substance."

As its title indicates, this is a guidebook for living, and through discussion of these two words, shmuck and mentsh, Wex sets out a blueprint for decent behaviour.

He gives us a multitude of examples of shmucks from the Bible, the Talmud, classic literature, and classic movies. Likewise for examples of mentshen.

He frequently cites that TV series by Matt Groening, whose Mennonite family tree apparently reaches all the way to Steinbach.

One kvetch is that Wex, who sells well in the U.S., uses no examples from Canadian writers. Certainly the works of Mordecai Richler, and Winnipeg’s Adele Wiseman, Ed Kleiman and Sheldon Oberman could have provided examples of both shmuck and mentsh.

The Talmud stories are the most interesting and display the most depth, while the movie examples are rather fluffy.

Not without wit himself though, Wex at times delivers zingers worthy of David Steinberg on the old The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour: "So strong is this latter feeling that the Bible commands the Jewish people to respect their enemies and erstwhile oppressors, which could explain why so many Jewish Community Centre parking lots are full of BMWs and Audis."

What ultimately converted this reader is Wex’s re-examination of the origin and meaning of the Golden Rule.

However, only a shmuck sticks a spoiler into a review.

Armin Wiebe is a Winnipeg novelist and playwright whose play The Moonlight Sonata of Beethoven Blatz uses the word mensch but not shmuck.