Here’s some expert advice: Don’t trust so-called experts

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/07/2010 (5584 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

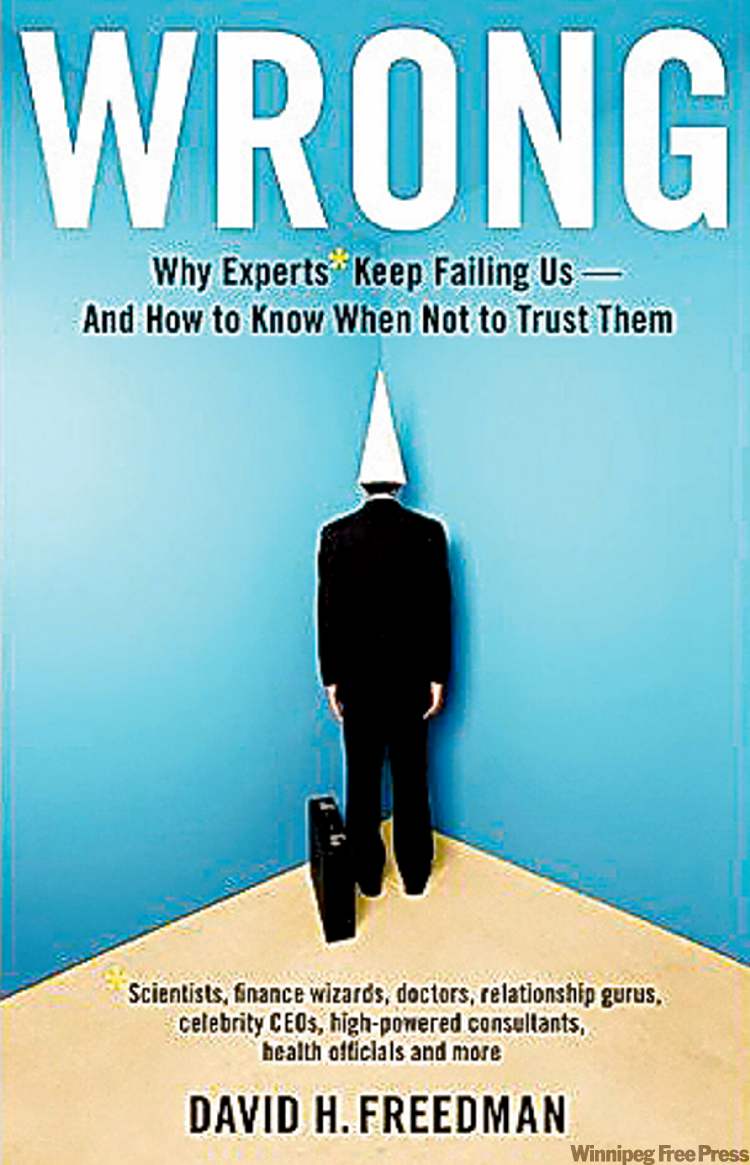

Wrong

Why Experts Keep Failing Us — And How to Know When Not to Trust Them

By David H. Freedman

Little, Brown and Co., 295 pages, $32

If you have ever been exasperated by conflicting expert opinion on swine flu, the latest miracle drug or global warming (or is it "climate change"?), Wrong is the right book is for you.

David H. Freedman, an American science and business journalist, has written a useful and entertaining (when it is not disturbing) guide to the reasons experts are mostly wrong and how we can learn to recognize advice that is likely to be right.

Freedman broadly defines "experts" as people usually quoted by the mass media as credible authorities, including pop gurus, celebrities and scientists.

Medical research is heavily dependent on animal trials and mice in particular. Many readers will be surprised by Freedman’s contention that very few mice studies are, in practical terms, applicable to humans.

Initial media excitement about medical breakthroughs based on mice trials rarely result in successful human treatments.

This is even more marked in psychiatric drug trials. Freedman quotes a Massachusetts Institute of Technology brain scientist saying, "When it comes to emotion and cognition, things are manifestly different in humans than in mice."

When you come to think of it, that sounds like expert advice likely to be right.

Researchers are not supposed to favour particular outcomes in their studies, but Freedman suggests that vanity, vested interest or careerism tempt many to twist the data to produce the results they want.

Part of the problem lies with the general public. We don’t like grappling with complex issues. We like our advice to be simple.

We particularly like advice that promises solutions without effort and we handsomely reward gurus who purport to tell us how to lose weight, make money and gain lifelong happiness without breaking a sweat.

A key factor in questionable research is that experts are often paid to get it wrong. Salaries, grants and careers often depend on producing results favorable to drug manufacturers.

Sometimes, companies even try to disguise their connection to certain findings by paying university researchers to put their names to studies actually written by the companies themselves.

Freedman maintains that researchers who question the integrity of their colleagues pay a high price. Strangely, he illustrates this by the case of MIT AIDS researcher Thereza Imanishi-Kari.

An assistant claimed her research had been falsified. The MIT establishment closed ranks around Imanshi-Kari and the whistleblower lost her job.

In fact, after 10 years, an independent appeal panel found there was no falsification and vindicated Imanishi-Kari.

A better example might have been that of Nancy Olivieri from the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto who endured years of intimidation by a drug company after revealing serious flaws in one of its products.

It is hard to avoid noting that Freedman supports his argument with favourable quotes from more than 30 experts from institutions including McMaster University, the London School of Economics and Yale, Berkeley and Oxford universities who agree with him. That seems a poor way to make the point that experts are usually wrong.

However, disarmingly, Freedman admits that he has indeed probably selected facts that bolster his case and that the experts he quotes may not always be right. Nevertheless, he believes he has demonstrated that most experts are likely to be wrong and, more importantly, has given the reader tools to help weigh expert pronouncements.

This he has done. His guidelines are enlightening. If we are willing to think critically, we need not be helpless before conflicting expertise. In other words, if we don’t bring our brains to the tasting, we shouldn’t complain about the snake oil.

John K. Collins, a retired Manitoba Teachers’ Society union representative, is proud not to be an expert book reviewer.