A peek inside the Hutterite world

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/10/2010 (5558 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

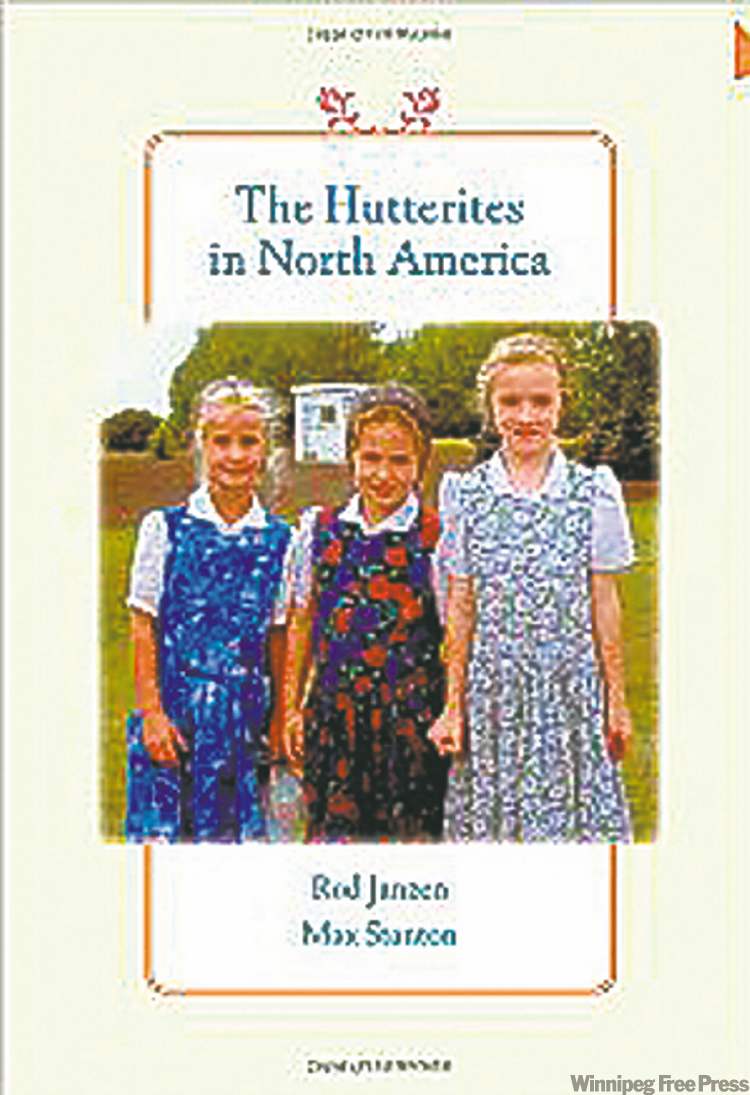

The Hutterites in North America

By Rod Janzen and Max Stanton

The Johns Hopkins University Press, 306 pages, $52

North America, and Canada in particular, is home to the highest concentration of Hutterites in the world. Yet, arguably, there remains no other culture on the continent about which so many know so little.

If you say “Hutterite” east of the Manitoba border, for example, you are likely to encounter comments like “how-to-right what?”

California historian Rod Janzen and Hawaii anthropologist Max Stanton spent years travelling to Hutterite colonies on both sides of the border, participating in the lives of people from the German-based subculture’s four main sects.

The result is a tome geared largely toward academia, but the lively nature of Hutterite people makes the book accessible to anyone who wants an up-to-date peek into this evolving culture.

Hutterite approval may vary, but this book is an important one. Janzen and Stanton have given both outsiders and Hutterites a gift.

The Hutterite faith was born in Moravia in the 16th century when Jacob Hutter, an Austrian hat maker, led a fledgling group of Anabaptists to a new kind of Christian community.

But the Hutterites’ belief in communal life, adult baptism and pacifism provoked intolerance from the state and the predominant religions. Hutter was burned at the stake in Innsbruck in 1536, as were many of his followers

Greatly diminished, the survivors found refuge in Ukraine in 1770 until their military exemption status was rescinded. They fled to the U.S. in 1874. Most relocated yet again, to Canada, during the First World War.

Hutterite commitment to the common ownership of goods sets them apart from the Amish and Mennonites and has distinguished them as the finest example of communal life in the modern world.

For more than 100 years there were three sects of Hutterites: the Leherleut, the most conservative; the moderate Dariusleut; and the liberal Schmiedeleut (now concentrated in Manitoba and the Dakotas).

In 1996, a split over leadership within the Schmiedeleut sect divided families and caused an exodus to mainstream evangelical Christian groups. The fallout created lawsuits and family rifts that continue to this day and may never be resolved.

“Write your book, then run,” Janzen was advised by one Manitoba Hutterite man when they came too close to the smouldering rubble.

Janzen spent time with members on both sides of the split, including the Acadia Colony near Carberry and the Fairholme Colony near Portage la Prairie.

In their first-hand research, the authors had to come to terms with the blunt Hutterite manner tempered by a devilish sense of fun.

“The no-holds-barred Hutterite persona is an important cultural tradition,” they write. “On the grounds of the Hutterite colony, there is little holding back, little inhibition.”

Hutterites have always lived isolated lives to guard against the influence of mainstream society, but with the computer age that’s not so easy anymore.

Until recently, they haven’t given a fig about what the outside world thinks of them, and that has fostered a certain mystery, but also great misunderstanding.

For example, the role of women is contrary to what most people would imagine, the authors report.

“It is true that Hutterite women do not have the franchise and do not attend policy decisions but they exert significant influence through the unregulated grapevine,” they say.

“Self-assured and full of ideas, they often interrupt Hutterite men in the middle of conversations.”

Hutteries are survivors. Throughout their bloody history, their faith and way of life have sustained them.

One can’t help but hope that when the smoke settles from the latest eruption that Christian love and brotherhood will be restored and bridges rebuilt so that this “amazing” culture continues into the next century.

The author of I Am Hutterite, Mary-Ann Kirkby lives in Prince Albert, Sask. Her new children’s book, Make a Rabbit, will be released this month.