Fischer’s endgame tarnished his legacy

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/03/2011 (5339 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Endgame

Bobby Fischer’s Remarkable Rise and Fall — from America’s Brightest Prodigy to the Edge of Madness

By Frank Brady

Crown Publishers, 402 pages, $30

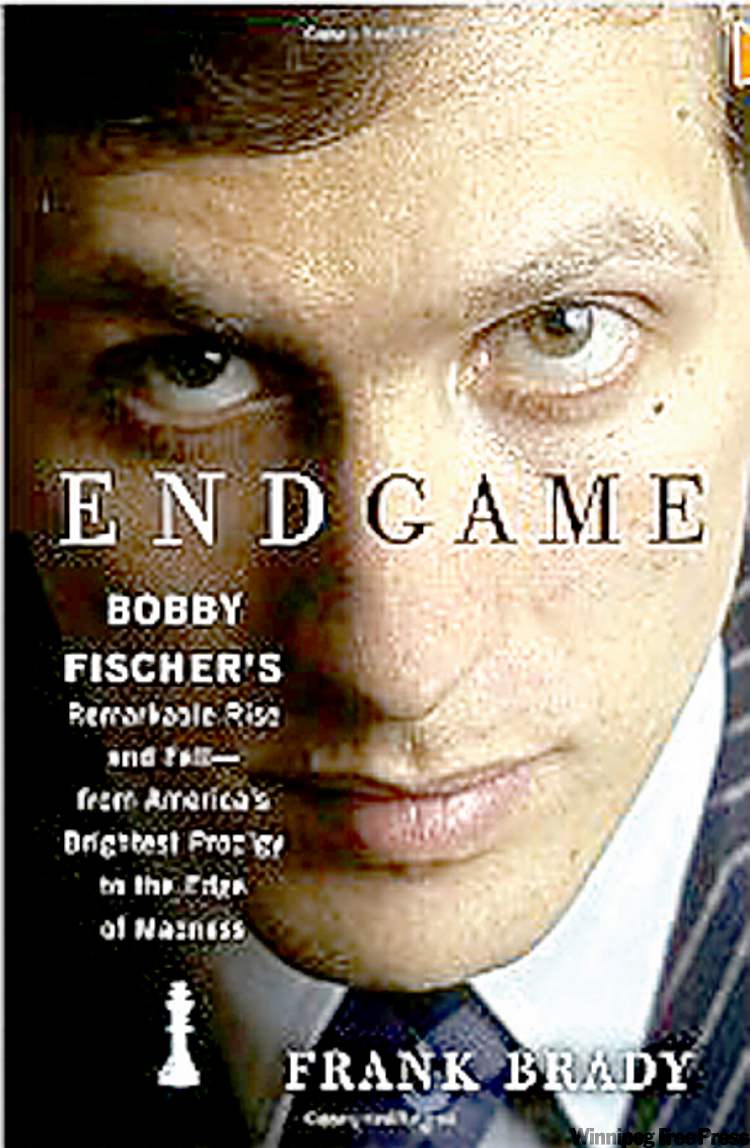

Nothing better captures the Bobby Fischer enigma than the two pictures on the dust jacket of this fascinating new biography.

On the cover, a young, striking, square-jawed chess genius stares straight ahead, locking his gaze on the photographer much like a predator would with his next meal. On the back, a decrepit, glassy-eyed, vacant Fischer, with a dirty beard and broken teeth, appears confused and totally lost.

There is no shortage of stories chronicling meteoric rises to the heights, only to be followed by equally rapid descents into ruin. But Fischer’s story is utterly unique, and it makes for engrossing reading, no matter what your level of chess understanding might be.

It’s hard to imagine anyone better qualified to write a definitive biography of the former world chess champion. Frank Brady is a professor of communications, a longtime chess organizer and someone who knew Fischer as a young prodigy. Some of his source materials date back to interviews in 1955 when Bobby was only 12.

But Brady’s familiarity occasionally clouds his analysis. He admires his subject so much that he tends to be forgiving, at times when condemnation would be much more natural.

Fischer rose quickly from obscurity to celebrity status. He became the youngest grandmaster in history at 15, and soon he was being touted as the great American hope to beat the mighty Soviets at a game they dominated.

But even in his teenage years, a pattern began to develop that would only escalate. He began making untenable demands, accusing his opponents of dirty tricks and cheating, and generally assuming the mantle of a brat in the chess world.

Fischer finally achieved his aim of winning the world championship by beating Boris Spassky in 1972. At the height of the Cold War he was a conquering American hero and the darling of talk shows and magazines. He was offered a ticker-tape parade in New York, President Richard Nixon personally lauded him, and rich endorsement offers poured in.

But the strain of devoting every waking hour to the fulfillment of a single aim finally began to show. Fischer retreated from chess, and from life generally.

He descended into a hermetic existence, systematically alienated all his friends, and with just one exception, never played another tournament match in his life.

Worse still, he became a raving anti-Semite, railing against international Jewish conspiracies and cabals. He stopped paying taxes and ran afoul of U.S. authorities by playing a rematch with Spassky in war-torn Yugoslavia in 1992.

Sneaking from country to country, he was arrested in Japan for travelling without a valid passport, and eventually was given asylum in Iceland. He died three years ago at age 64, having lived a year for each of the squares in a chessboard.

Even for readers familiar with Fischer’s story, Brady finds new and revelatory details. Fischer’s mother had lived in the Soviet Union, and later was an activist in the U.S., so authorities believed she might be a spy. Brady accessed both FBI and KGB files to enrich his storytelling.

Brady’s narrative is at its best when he interweaves Cold War politics with the events of Fischer’s life. When a typical last-minute demand by Fischer for more money was threatening to scuttle the world championship, for instance, it was the intervention of national security adviser Henry Kissinger that provided him with an additional nudge to play.

Clearly, though, Brady likes Fischer and was flattered to be in the presence of genius. This leads to minimization of some of his more egregious actions and utterances. In the end, no matter how brilliant he was at the board, Fischer’s legacy as a person will be forever tarnished.

Cecil Rosner is managing editor of CBC Manitoba and an occasional tournament chess player. He writes a chess column for the Free Press.