Not enough emotion, not enough sympathy

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/07/2011 (5242 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

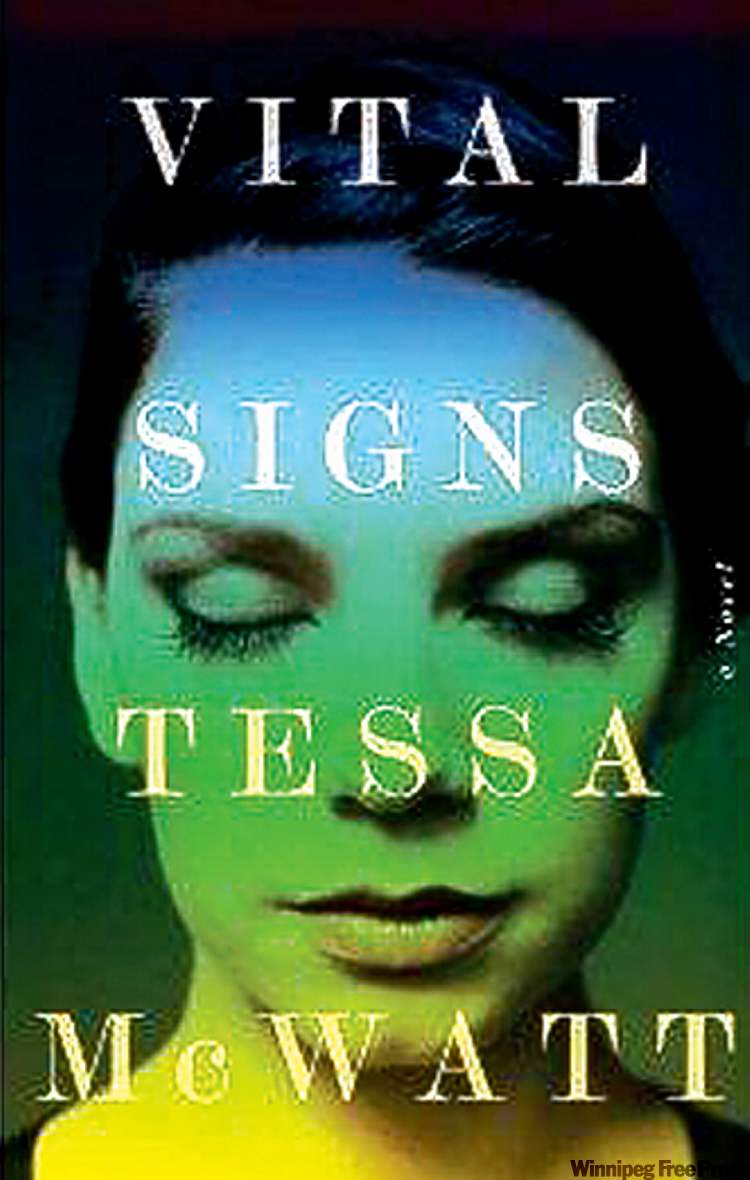

Vital Signs

By Tessa McWatt

Random House Canada, 165 pages, $25

THIS short literary novel has a sympathetic story at its centre, but an almost wholly unsympathetic narrator at its emotional heart.

Author Tessa McWatt, Guyana-born and Toronto raised, tells of a long-married couple. The woman, Anna, has an aneurysm, which requires a dangerous but life-saving operation. She chooses to have it and awakens from it.

In flashbacks we see bits of their life, its crises, and her husband Mike’s affair. Grown children show up to have their say; the couple endures.

One is drawn to the outline of the story, and part of its telling.

For example, Anna has confabulation, which medically means filling in gaps in memory with fabrications one believes to be true.

Her mixing up of words has its fascination, as she attempts to express her inner world. The idea of loss, and the fear of how to cope with the unimaginable, is strong in the book.

Unfortunately, we get the story through the insufferable ramblings of Mike, a graphic artist and dispenser of overblown imagery. Random example: “The July corn is like a teenager, gawky and nearly as tall as it ever should be,” or “the ears are bulging like oblong testes.”

Mike also “mutilates an hour,” and, on the first page, a thought comes to him “like a dog comes to its master.”

Mike tells us he is overwhelmed by the situation, since he doesn’t feel worthy of his wife, but the gentleman protests too much.

McWatt received a Governor General’s Award nomination for her second novel, Dragons Cry, in 2001. In Vital Signs, she attempts to create a protagonist who both loves and resents his wife, but she never manages to make either emotion urgent or sympathetic enough in the narrative to persuade the reader.

Two things stand out that defeat the idea. First, all we know is what Mike tells us, and he is judgmental of everything and everyone, especially his children, whom he regards as failures.

Yes, he likes Sasha, the free-spirited youngest, the best, but doctor son Fred and upwardly striving yuppie Charlotte come in for some silent fatherly stares and recriminations.

And on it goes. He judges all, from his put-upon mistress Christine, to the guides on the trip he and Anna took to Egypt, to the cafeteria in the hospital where she is staying.

Next, and even more central, is the place of sex in the couple’s relationship. Mike gets a lot, and misses it. He wonders, in his own supposed loving way, whether one should have sex with a woman who has an aneurysm, though Anna is finally willing.

That occurs after he happens upon her having an encounter with a washing machine serving as a vibrator. He withdraws “guiltily,” but that’s another point not in Mike’s favour. He is a braggart of supposed guilt about Anna, and smug about it.

The sex is never linked with deep feeling, but only with his smugness. Until about halfway through the novel, one hopes that is meant as the darkest of satire, or deepest irony. Perhaps McWatt is using this tone to expose a man unaware and wrongheaded.

No such luck. We are to accept him with some sympathy, and it becomes obvious why.

Peppered throughout are drawings Mike has created to communicate with Anna since language fails. They are by artist Aleksandar Macasev, and intriguing.

Mike is more than a graphic designer; he is clearly an artist projecting emotions and situations onto his wife. To McWatt, therefore, he is poetic and sensitive. That’s why Mike should be the hero.

It won’t wash, but there it is.

Rory Runnells is the artistic director of the Manitoba Association of Playwrights.