Stability proves elusive in troubled Afghanistan

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/01/2014 (4295 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It is said that life in a war zone is cheap, but conditions in southern Afghanistan in the last century have been singularly difficult.

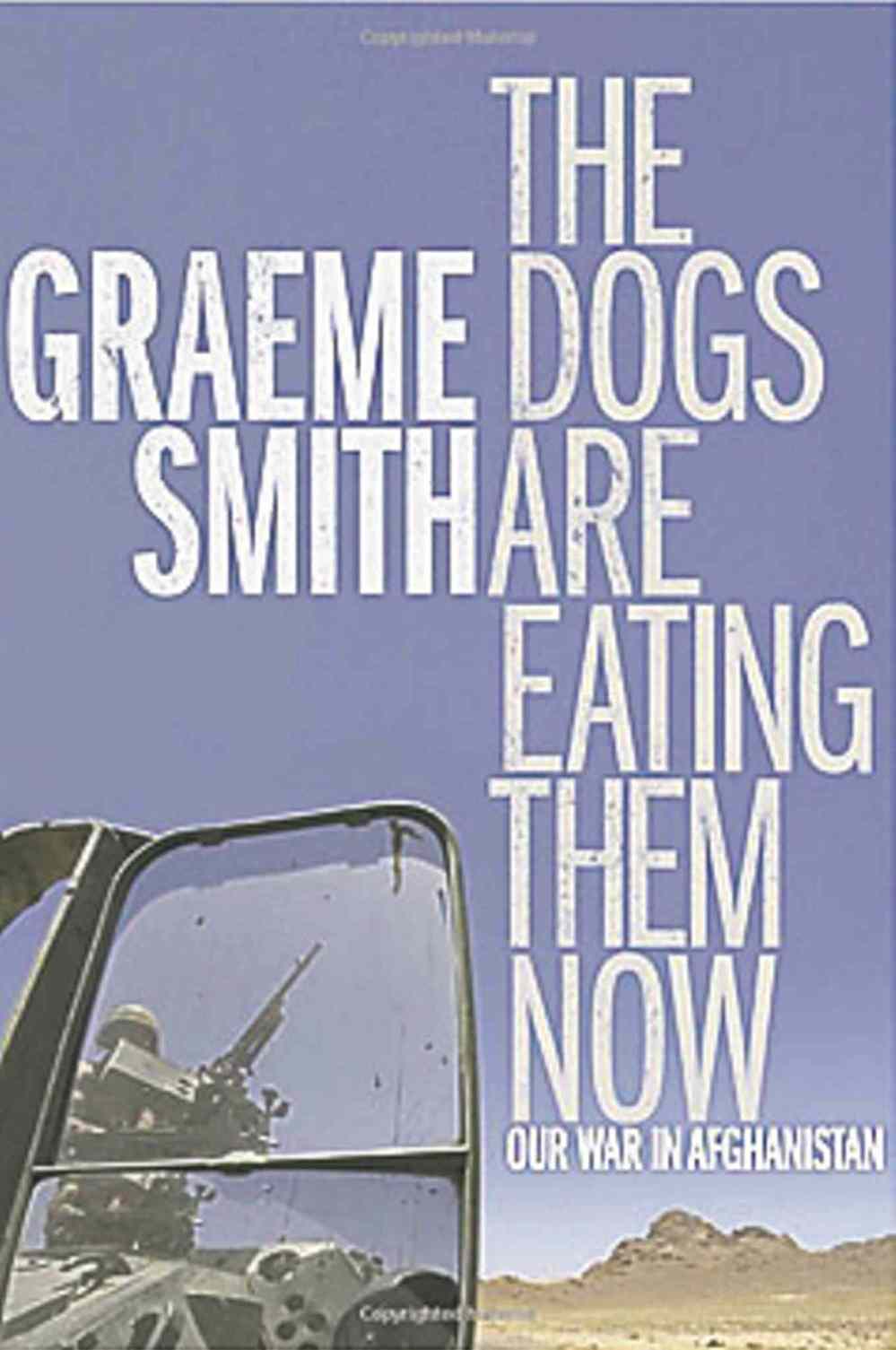

In a style marked by smoothness as well as clarity and exceptional detail, Canadian foreign correspondent Graeme Smith describes the stressful state of conditions in Afghanistan, particularly the southern part.

He was 26 and full of optimism when he arrived in the troubled country in 2005 with his Globe and Mail assignment. He hoped to find Canadian and other NATO troops supporting some kind of democratic lifestyle.

Altogether Smith visited southern Afghanistan 17 times from 2005 to 2011, working independently of the international forces, and also spending time with U.S., Canadian, British and Dutch troops.

Though he strove to maintain a positive view, and even developed an affection for the beleaguered country, he quickly recognized the likelihood that Canadian forces and other NATO units were bound to fail in efforts at preserving stability.

Among Smith’s difficulties in southern Afghanistan was that he stood out as a foreigner. Everybody seemed to know it, even though he wore local clothing (the long shirt, for example). Though many people spoke English, he was careful in its use, except with friends.

He managed to find and employ a number of translators, who served as informers. And in spite of the Taliban, he makes friends and collects information that helped him write and file reports and journal articles. Much of his research and interviewing had to take place with him concealed in the hot back seat of a car with the windows closed.

Danger was constant. One minute people were sitting at a table drinking tea; seconds later they were diving under the furniture in response to an explosion.

One reality to which it took Smith time to adapt was the constant danger of being shot at or blown up by bombs, especially ones embedded in the ground. Meanwhile the NATO troops were aggressive in their encounters. Their outings took on the nature of “hunting expeditions” against the insurgents.

A major issue arose between NATO forces and the Afghan system — charges that prisoners turned over to the local forces were beaten and tortured. Smith, as well as some other journalists, helped expose such practices.

One of Smith’s bolder efforts was to meet and compare possible plans with the Taliban. Contrary to expectation, these frontiersmen did not strike him as being so vicious or aggressive.

As Smith notes, “The Taliban did not seem like men who necessarily wanted to crash planes into distant cities, and most of them would never see a skyscraper in their lives.”

A meeting Smith did not find useful to seek was one with President Hamid Karzai. Unlike the NATO forces which were active in the front lines, “risk-taking was not fashionable in the Afghan government.” To find even an Afghan police chief took exceptional patience and assistance from local citizens.

Finding a police chief was no great bonus anyway, as corruption was so rampant that cops were more than likely to be responsible for crimes.

Actually crime was difficult to define in Afghanistan. Crime was so much the norm that fighting it was futile.

Yet the cultivation of poppies was regarded by the authorities in Afghanistan as illegal. It seems to have been just about the only policy of the local government. Meanwhile, foreigners criticized it as the foundation of international traffic in drugs.

Smith arrived in Afghanistan believing that Canadians and other NATO forces could establish a moderate and stable state in Afghanistan, yet they failed, unable to manage the basic test of statehood: monopoly on the legitimate use of violence.

Ron Kirbyson is a Winnipeg writer and educator.

History

Updated on Saturday, January 11, 2014 8:41 AM CST: Tweaks formatting.