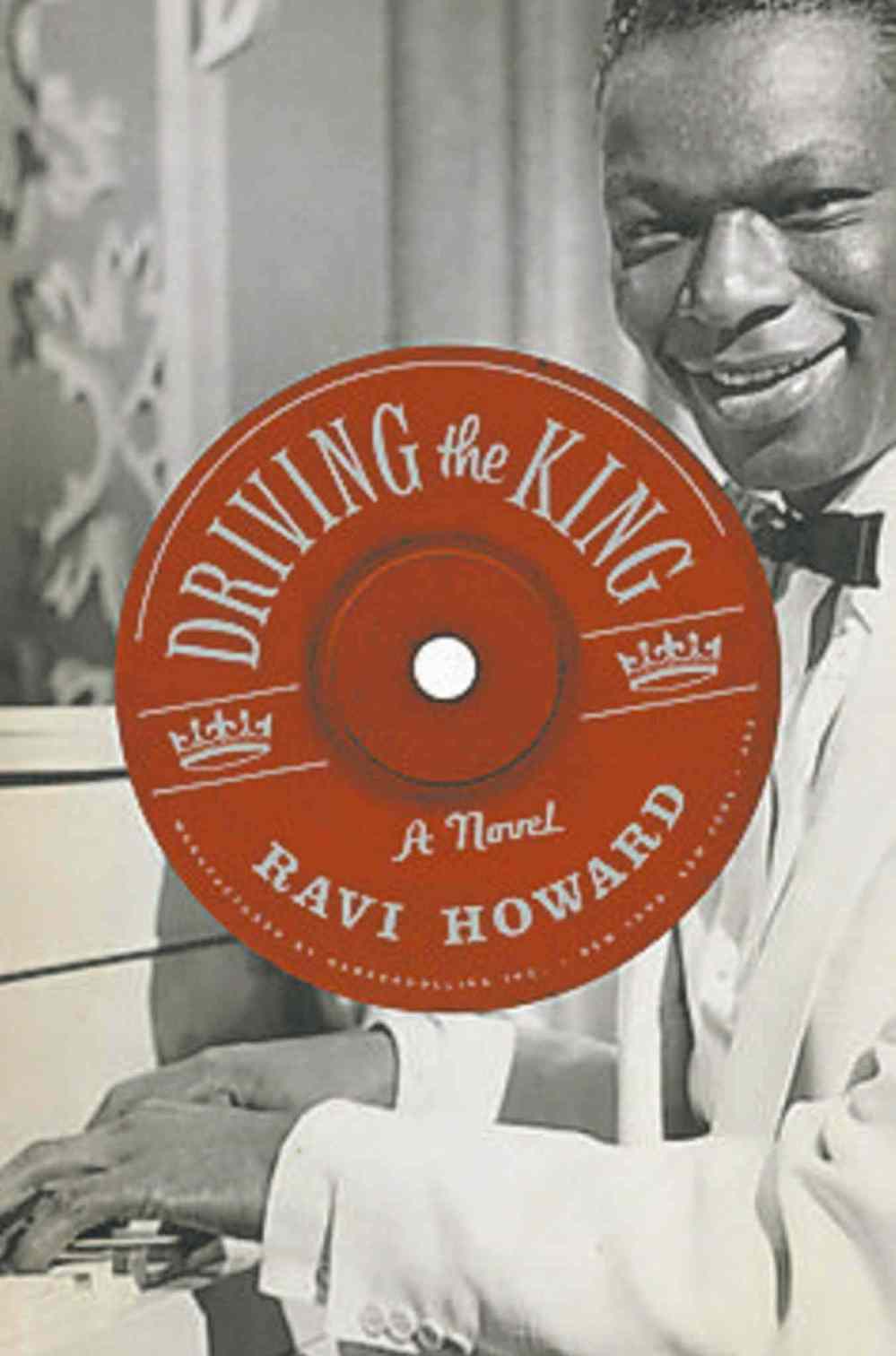

Fictionalized account of Nat King Cole explores civil-rights movement

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/01/2015 (3914 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

This fictional tale of two Nats — singer Nat (King) Cole and Nat Weary, a childhood friend who saves Cole’s life — really aims to tell the story of life in the Jim Crow South and the year-long bus boycott that brought Rosa Parks and the African-American people of Montgomery, Ala., to national attention.

Weary has just returned to his hometown from fighting in Europe in the Second World War, and has taken the love of his life, Mattie, to a Nat King Cole concert. Weary carries a ring in his pocket hoping she will accept his proposal of marriage; Cole has agreed to sing a song for the couple.

In a moment, the lives of all three are radically altered.

Before Mattie can give her answer, Weary spots a group of white men carrying pipes heading for the stage and Cole. He leaps from the “coloured” balcony and beats the would-be attacker nearest Cole with a microphone, saving the singer.

For his noble act in defence of his friend, Weary is sentenced to 10 years in prison. The white attacker gets three years.

In real life, Cole was attacked in Birmingham, Ala., not Montgomery, and was rescued by police, not by a friend. After that, he chose not to perform in the South again.

American author Ravi Howard changes Cole’s story so he can portray the courage shown by the Montgomery bus boycotters in the face of racist laws, and to give readers a sense of the courage that started and sustained the civil-rights movement. Howard portrays strong women whose bravery matched that of Rosa Parks, but who did not appear in the national spotlight.

His fictional story, despite historic alterations, conveys a feeling of truth. And Weary is the ideal narrator: his hard 10 years in prison have cut him off from the news, and the reader sees the civil-rights battle lines through his neophyte eyes.

The book opens on the day Cole returns to Montgomery to finish the concert that was disrupted more than 10 years earlier. Weary’s story moves seamlessly through time from the fateful concert and his hard prison time to his role as Cole’s driver, bodyguard, confidant and promoter of the new concert.

Cole stuck by his friend, and after Weary’s release from jail, he moves to Los Angeles to work for the singer. Of course, L.A. is not free of racism — it may not have gun-toting bus drivers as in Montgomery, but Cole has bodyguards and his property is monitored by security nonetheless.

Cole’s foray into network television is destined to fail; even though he was a successful singer with hit records, he was still a black man on TV, and big advertisers threw their money at variety shows hosted by white performers.

Nat King Cole serves as more of a device here, but an important one. The singer gives Weary a second chance after all he has lost, allowing him to find freedom from the demons he carried from wartime and prison time.

In a memorable scene, Weary drives Cole to the prison where he served his time to fulfil a promise he made to his fellow inmates. The guards assume by the expensive Packard Weary is driving that his passenger must be white, and do not order them away from the prison work gang.

Cole can’t sing for the inmates, of course, but is able to roll down the window so he can be recognized, and to throw packages of cigarettes into the weeds to be picked up by the prisoners. And, most importantly, to prove Weary is a man of his word.

Driving the King aims a lens on the burgeoning civil-rights movement of the time. Nat Weary’s detached lens captures the injustice that fuelled the need for a civil-rights movement, as well as the courage of the people who fought for those rights.

Chris Smith is a Winnipeg writer.