Métis culture, tradition and lack of rights given new perspective

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/04/2015 (3886 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

While many Canadians may use the term “Métis” loosely to describe individuals who are descendants of both First Nations and European ancestors, others would not have it so. For example, the Métis National Council defines the Métis as “a people with their own unique culture, traditions, way of life, collective consciousness and nationhood.”

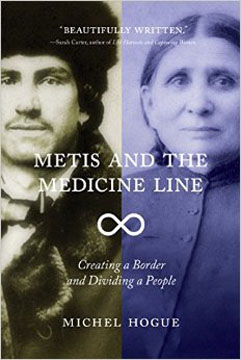

This more precise and historicallyn located definition is captured in Michel Hogue’s excellent new study of Métis people in the 19th century, Metis and the Medicine Line: Creating a Border and Dividing a People. Published by the newly created University of Regina Press, Hogue provides a detailed, well-researched account of how this Prairie people developed its own customs and traditions while, at the same time, moving back and forth according to economic necessity across the U.S.-Canada border.

Hogue purposely excludes the accent on the “e” in Métis, arguing that the accent leads us to think mistakenly that it is their French ancestry that defines them, rather than their customs, economic practices as well as diverse ancestry as a borderlands people. As the accent is more commonly used north of the border, perhaps the author is more worried about misleading his American readers.

Accent or no accent, Hogue examines the lives of these 19th-century borderlands people who increasingly found themselves both connected to, and separate from, First Nations tribes and the newly arriving European settlers. Rather than focus on such well-known leaders as Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont and the politics of the Red River settlement, the author examines broader social and economic activities relating to the buffalo hunt, trade relations with European and First Nations people, and kinship ties between communities through marriage.

Added to this complicated scenario is the enforcement by the U.S. Cavalry and North West Mounted Police of the Canadian-U.S. border, termed at the time as the “Medicine Line” due to its growing power over many local affairs.

Hogue, who teaches history at Ottawa’s Carleton University, presents a very solid piece of scholarship based on excellent sources, including letters written by Métis and others plainspeople, state agents, government records and other historical documents. Added to this are 19 photographs and three maps that capture the fact that indigenous peoples who moved freely across the international border formed at one time a distinct region within the North American continent. As mobile fur traders were replaced by newly arriving settlers seeking to plant roots on their farmlands, and as indigenous peoples who had travelled throughout the Prairies were now locked onto specific locations by newly signed treaties, the international border became significant in dividing the one territory into two national sub-regions.

The tragedy for the Métis and others who were simply labelled “half-breeds” (a legal term at the time, as found in the Manitoba Act) was that both the American and Canadian governments came to treat them as a “mixed blood race” with no collective rights of their own, and as individuals on the margins of First Nations communities. As part of this marginalization, the federal government stood aside while many were swindled of their lands by unscrupulous land dealers seeking to profit from the incoming wave of European settlers arriving from Ontario.

Sometimes chickens do come home to roost. In 2013 the Supreme Court of Canada determined that from 1870 onward the federal government failed in its promise to grant lands to the Métis and others of mixed aboriginal heritage in the region.

Michel Hogue’s Metis and the Medicine Line provides an excellent examination of the historical factors underlining how a people could be shut out from their own lands and economic practices during the the 19th century — an era that continues to influence us in the 21st century.

Christopher Adams is the co-editor of Métis in Canada: History, Identity, Law and Politics published by the University of Alberta Press, and is the rector of St. Paul’s College at the University of Manitoba.

History

Updated on Saturday, April 25, 2015 8:10 AM CDT: Formatting.