Memories a riveting road map through Occupation-era Paris

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/12/2015 (3596 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

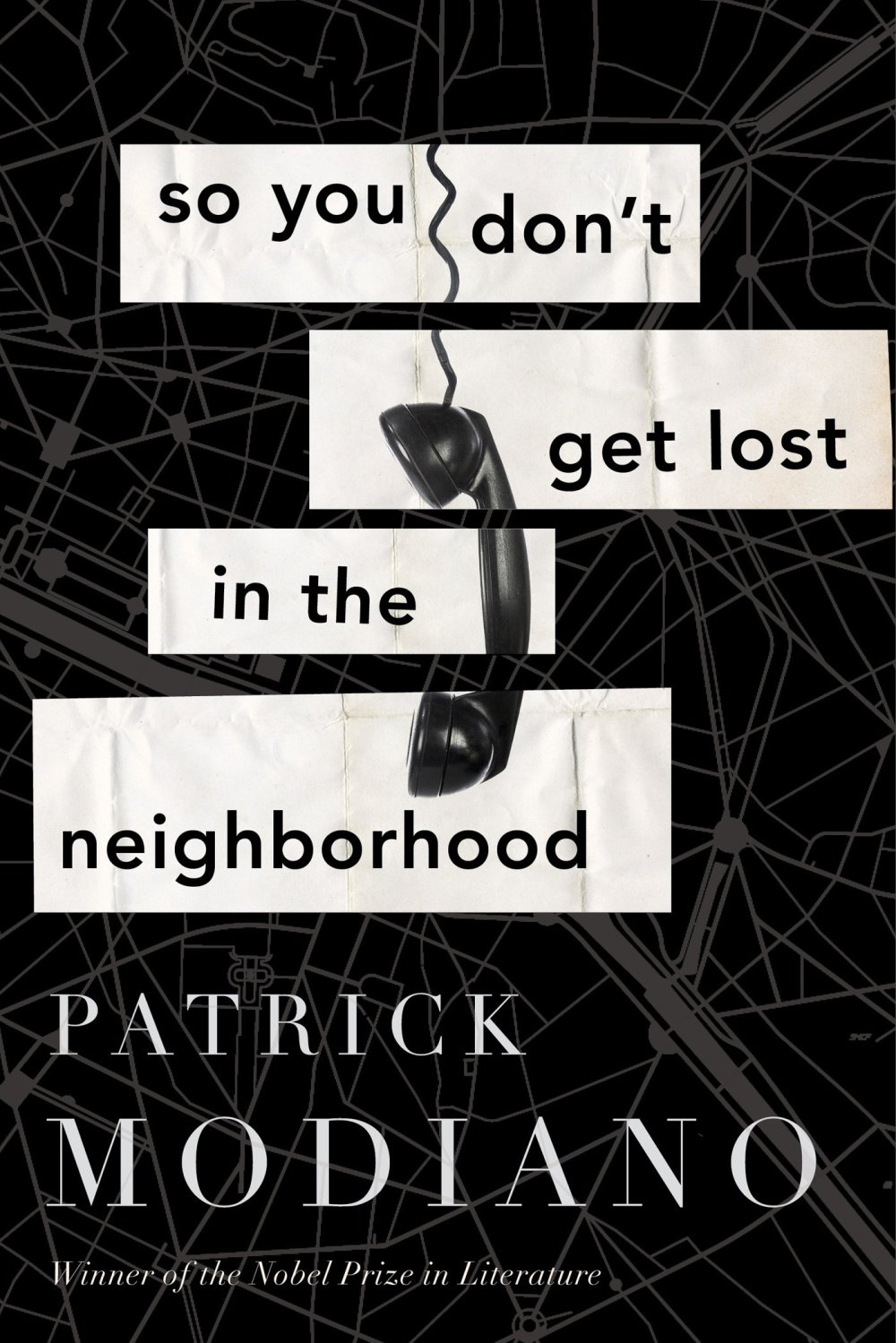

Patrick Modiano’s So You Don’t Get Lost in the Neighborhood begins with a quotation from Stendhal: “I cannot provide the reality of events, I can only convey their shadow.”

This is a novel full of shadows — shades of a dimly remembered past that slip away almost as soon as they appear.

Jean Daragane is an aging novelist who has subsided into complete reclusion in his Paris apartment. One afternoon, the telephone rings for the first time in a very long time. The voice on the line is “dreary and threatening,” almost certainly the voice of a blackmailer, Daragane thinks. Despite himself, Daragane agrees to meet the man and his mysterious girlfriend, Chantal Grippay, and finds himself revisiting his own long-mislaid memories.

The novel is Modiano’s latest since the French author won the 2014 Nobel Prize for Literature, “for the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the Occupation.” Published first in French under the title Pour que tu ne te perdes pas dans le quartier (Gallimard, 2014), this novel has since been released in 20 languages, including this English translation by Euan Cameron.

Neighborhood is typical of Modiano’s lifelong literary preoccupations; set in Paris, much of the novel’s muted (and mostly past-perfect tense) action takes place during the Occupation during Daragane’s childhood. Daragane’s memories are tied to famous streets, to historic addresses — the Moulin Rouge, the Louvre des Antiquaires.

But Daragane’s memories are personal, not political. In them, characters arrive and disappear, their names changing, their activity appearing suspicious only in retrospect. Somewhere in the milieu, a woman is murdered. Daragane-as-a-child seems only to be aware of his own fear of abandonment, while the adult Daragane remembers specifics only with reluctance, and attaches few names to his fears.

Neighborhood reads like a restrained thriller. Scenes are pared down, as crisp and stylish as a black-and-white movie — one part Hitchcock, one part Hepburn. Modiano carefully curates his symbols: the telephone, Daragane’s only link to the world, is weighty with the threat of unwanted communication; Chantal’s vintage black-and-gold dress awakens troubling memories of a woman from Daragane’s sunken past.

An aspen tree outside Daragane’s window is another important symbol. He looks at it to regain his emotional footing. “In periods of disaster or mental anxiety, all you need do is look for a fixed point in order to keep your balance and not topple overboard,” he reflects. “This aspen on the other side of his windowpane reassured him… he felt comforted by its silent presence.”

That Daragane is a man in need of comfort is a fact that increasingly impresses itself on the reader, along with his fear of other people, of activity outside his routine. “For some time his reading had been reduced to just one author: Buffon,” writes Modiano. “He derived a great deal of comfort from him, thanks to the clarity of his style, and he regretted not having been influenced by him: writing novels whose characters might have been animals, and even trees or flowers.”

Like a timeless black dress, this is a novel of deceptive simplicity; every sentence is psychologically evocative. Modiano does not let Daragane retreat to his comforts — this is the point of So You Don’t Get Lost in the Neighborhood.

But the point is made gently.

Julienne Isaacs is a Winnipeg writer.