Wolfe pack

Indian Posse co-founder's presence posed threat within prison

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/05/2016 (3451 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In the world of outlaws and gangbangers, few reached the legendary status of Danny Wolfe.

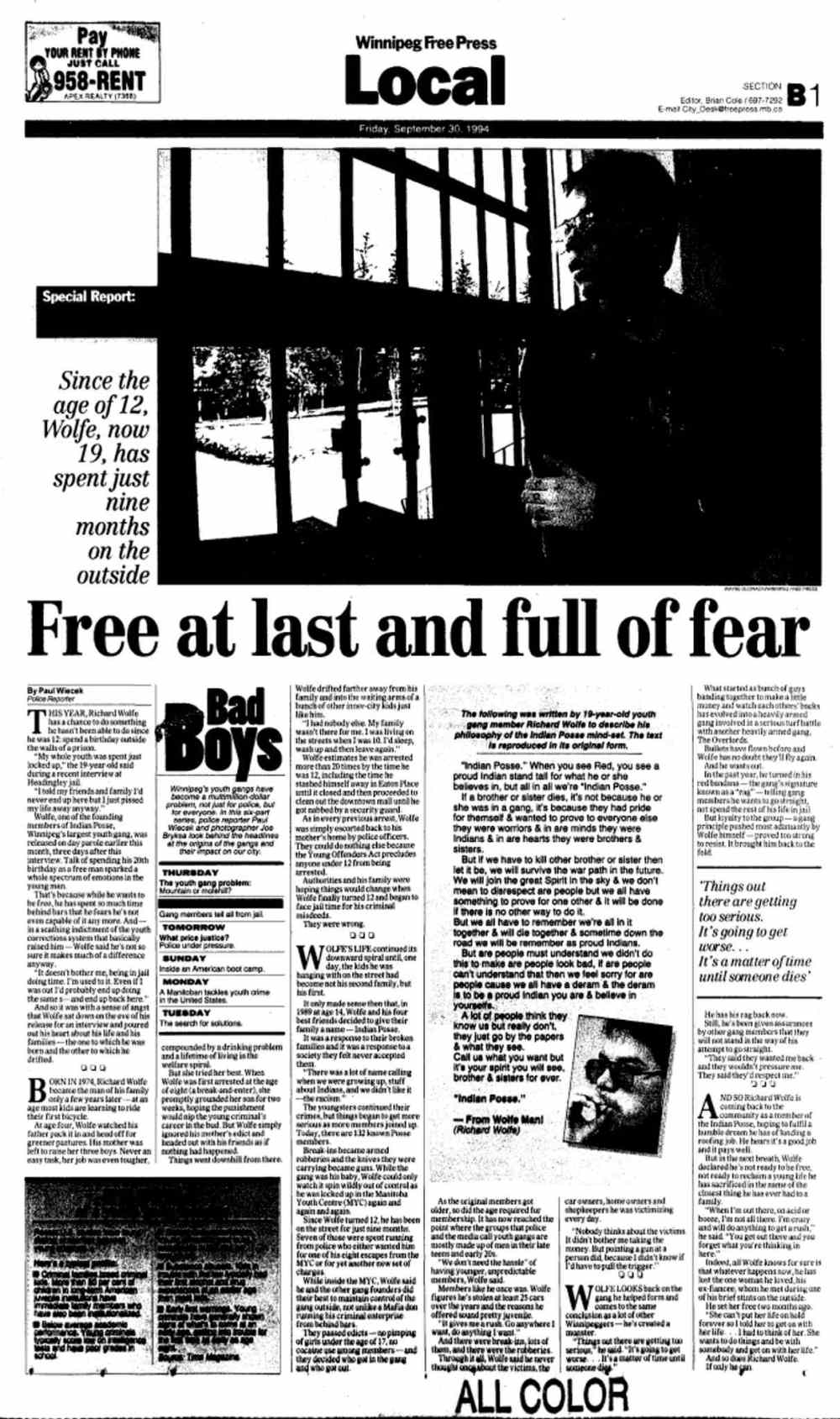

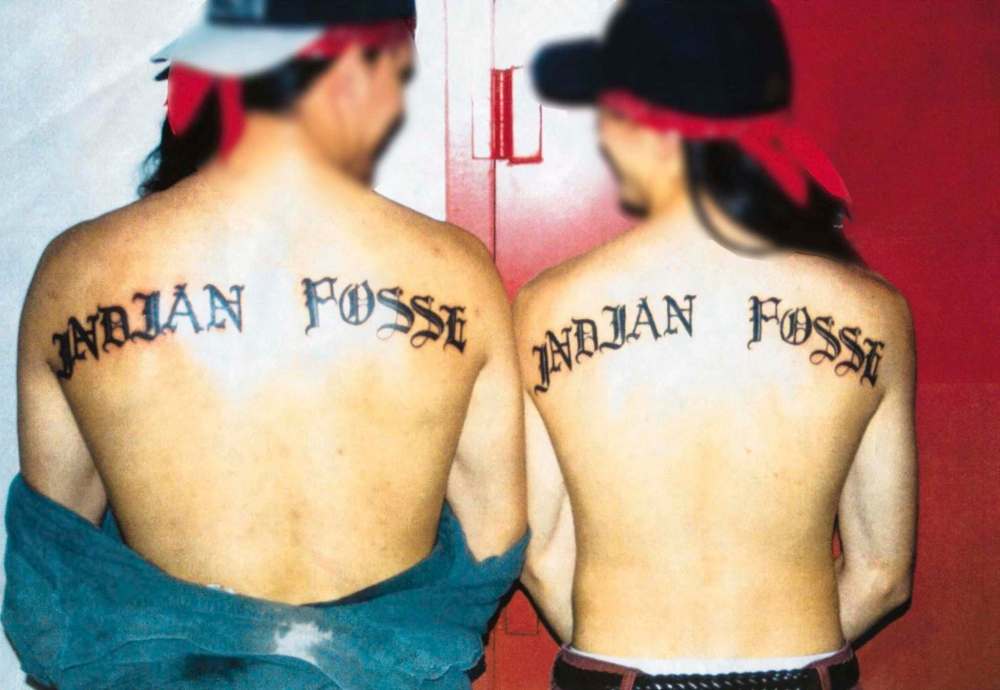

Wolfe, along with his brother Richard, co-founded the Indian Posse in 1988 in Winnipeg. The Posse was Canada’s first and largest aboriginal street gang – eventually boasting 12,000 members.

Wolfe, who had his first brush with the law at age four, took part in a brazen jail break with five other inmates at the Regina Correctional Centre in 2008.

In 2010, he was killed in a brawl involving at least 10 other inmates inside Saskatchewan Federal Penintentiary near Prince Albert.

Wolfe, 33 when he died, had been sentenced to life in prison after being convicted of killing two people and injuring three others during a Saskatchewan home invasion.

The Ballad of Danny Wolfe: Life of a Modern Outlaw examines Wolfe’s upbringing and the system and society in which he lived.

* * *

ARRIVING AT THE MOUNTAIN

1995-96

The note of warning that preceded Danny Wolfe’s arrival at the Stony Mountain penitentiary was spelled out in block capitals. It distilled what the justice system knew of Danny on Sept. 20, 1995, the day he set foot inside “The Mountain” for the first time: “HIGH-RANKING INDIAN POSSE GANG MEMBER.”

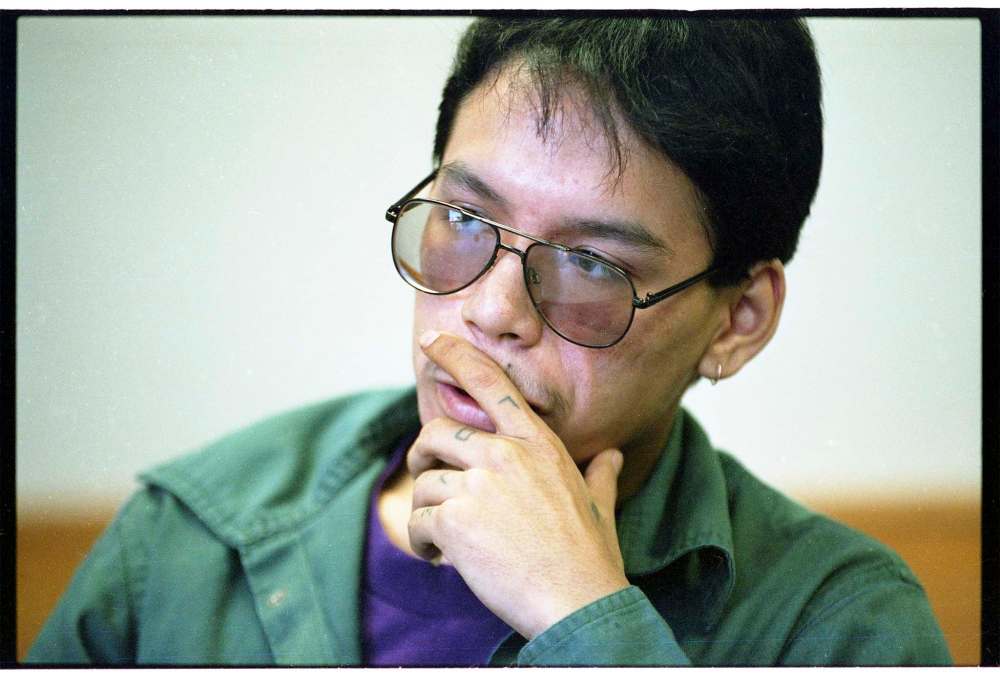

The note was handed to the sheriffs who transported Danny by van from the Remand Centre (where prisoners await trial) in downtown Winnipeg, and the sheriffs then passed it to the guards at the penitentiary when they delivered Danny to his new home later that morning. It’s not clear whether the block capitals were for ease of reading or emphasis. It might have been difficult to convince the sheriffs that this quiet 19-year-old, who weighed about 120 pounds, was to be treated with extreme caution.

Danny was arrested the day after he threatened Darryl and Christa in May 1995. It didn’t take long for police to find him, as they’d been questioning him in connection with the attempted murder barely 12 hours before. He submitted quietly. He was charged with obstruction of justice and using a firearm in the commission of a crime — a small price to pay, in his view, if it helped set his brother free.

Bail was set at $10,000, a sum he could have raised but didn’t. In those days, prisoners on remand were given credit of two days of time served on their eventual sentence for every day spent awaiting sentencing.

When he walked through the gates of the federal penitentiary, his peers treated it not as a failure, but as an achievement. By receiving federal time he had reached a senior level in the gang. Danny was a founder, of course, but that had never been enough to guarantee a position at the top of the gang. It had to be earned.

On arrival, as part of the intake process, Danny submitted to a battery of psychological tests and interviews that revealed a great deal about him.

Among gang members, particularly those still in their teens, bragging about rank and status is often overblown. Danny, however, tried to sound as humble as possible when speaking to the psychological assessors. He played down his status, telling his interviewer that he wasn’t a high-ranking member, despite the intelligence reports to the contrary. He was just one level above a striker, he said.Danny had no bank account, no credit, no collateral, no hobbies and his relationships were described as predatory.

Both of those statements are probably true. Danny wasn’t on the gang’s council, its highest rank, in 1996, but he was no mere foot soldier either. He was one level below the top. In the gang world that meant he could “earn” by taking a portion of what more junior members made selling drugs or committing robberies.

Still, prison officials were skeptical of Danny’s story. In their eyes he was an Indian Posse leader and his mere presence posed a threat within the institution. During his first lengthy interview, Danny explained that leaders could be easily identified because they had the right to speak on the gang’s behalf. He did not have that rank, he said. But then he raised eyebrows with a frank statement about what he intended to do once he was admitted into the prison population.

“He states that when he enters the Stony Mountain population he will go and talk to other members of the gang and find out what they are doing (i.e., selling drugs, taking programs, etc.). He states he will then do what he thinks is good for him and he does not care if the other members want to follow him or not,” the interviewer wrote in his prison file.

That’s not typically how things work in prison, a highly regulated world where those who break norms place themselves at risk. Danny’s attitude was taken as proof that he enjoyed what they called “the privileges of a high-ranking senior member.”

Over the next few months the psychologists and psychiatrists who met with Danny compiled a long list of issues he needed to confront. His life story, as they summarized it, read like a guide to building a sociopath.

His parents were absent and their relationship was abusive and dysfunctional, creating an absence of family ties in childhood. Some of his family members were criminals. He was socially isolated and easily influenced by others, and had mostly criminal friends who abused substances. He didn’t use hard drugs because the gang forbade it, but he sold drugs for profit.

They described the area where he lived, the North End, as “criminogenic,” meaning likely to cause criminal behaviour. Danny had no bank account, no credit, no collateral, no hobbies and his relationships were described as predatory.

A prison psychologist who spent some time with Danny described him as a “high energy” individual who showed signs of underlying anger and anxiety. Danny had relatively low ego strength, the psychologist wrote, which partly explained his impulsiveness and inability to deal with frustration. The family history of abuse and neglect was a contributing factor to his difficulties forming attachments.

“Somewhat nervous,” the psychologist noted in a looping scrawl. “Likely to ‘get involved’ in [the prison] population.”

Stony Mountain is Manitoba’s federal penitentiary, a medium-security jail about 25 kilometres north of Winnipeg. It is also the de facto seat of government for the Indian Posse. The prison council inside the jail is home to the gang’s senior leadership, sometimes referred to as “the circle.” In theory, the circle at Stony Mountain calls the shots.

In the four months of dead time before he was sent to Stony Mountain, Danny began to step out from [his older brother] Richard’s shadow. He organized an extortion racket in the Remand Centre, where he forced prisoners to either pay him protection money or face a beating, according to a prison intelligence report. He also ejected some members of the gang by “rolling” them out – in other words, by initiating a vicious beating.

Danny got so cocky he walked around with the Indian Posse logo painted on his jail uniform, a provocation that resulted in a formal disciplinary procedure. He might have seemed quiet, the disciplinary report suggested, but he was dangerous, and extremely influential behind the scenes. He was becoming a leader in his own right.

Three months after his 20th birthday, on Oct. 6, 1996, Danny met with prison psychologist Richard Howes in a private room at Stony Mountain for an extended evaluation. The purpose of the meeting was to see whether Danny could qualify for early release. Dr. Howes began with Danny’s early life. He asked him when he had last seen his father. Danny provided a very specific answer: it was in 1988, the same year the gang was founded. He told Dr. Howes about not having seen his father in years and then bumping into him on the street, only to be ignored. The psychologist described it in his notes:

After greeting his father and a brief exchange the father moved on with a rather lame “See you later.” The 12-year-old Mr. Wolfe thought to himself, “That’s my dad. Why doesn’t he even want to talk to me?” and in fact he never talked to his father or even saw him again. It is relatively easy to see the attraction of a gang to a young boy who felt so hurt and neglected by the one man who should have cared about him.

Mr. Wolfe has been described in previous reports as a “street orphan”, and I have no doubt the neglect and inadequacies in his childhood led him to willingly join his older brother in the founding meetings of the Indian Posse, which he says took place in his mother’s home when he was just 12 in 1988.

“We had nothing,” Danny told Dr. Howes. He and his friends were raised in impoverished, broken homes surrounded by alcohol and violence. Dr. Howes recorded his observations that the Indian Posse had provided “a sense of ‘strength in aboriginal unity’” for Danny and “friends that loved one another.”

Dr. Howes concluded that forming a gang, given Danny’s circumstances in life, was perfectly understandable, but his membership in the gang made it much likelier that Danny would live his whole life as a criminal.

He had surrounded himself with people who held selfish, exploitive criminal values and “who live in an undisciplined, hedonistic fashion” that Danny embraced. “For as long as he chooses to maintain [his place in the gang] he is unlikely to pursue any sort of conventional life, for such would be the antithesis of all he has experienced and practiced,” Dr. Howes wrote.

Danny wanted the psychologist to understand that there was something different about the Indian Posse, that it was more than a typical street gang.

“When we first started it was all crime,” Danny told him. But as the gang members grew up, the Posse became a source of aboriginal spiritual teaching, a way for kids raised without their families’ stories to understand their place in the world.

Together they attended sweat lodge ceremonies, smudged with sweet grass, and carried medicine bundles, or at least they did when they were in Stony Mountain, where these services were provided for indigenous offenders.

Above excerpted from The Ballad of Danny Wolfe by Joe Friesen. Copyright © 2016 by Joe Friesen. Published by Signal, an imprint of McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company. All rights reserved.

History

Updated on Saturday, May 7, 2016 7:55 AM CDT: Typo fixed.