Coming-of-age story gets a little too silly

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/07/2016 (3476 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

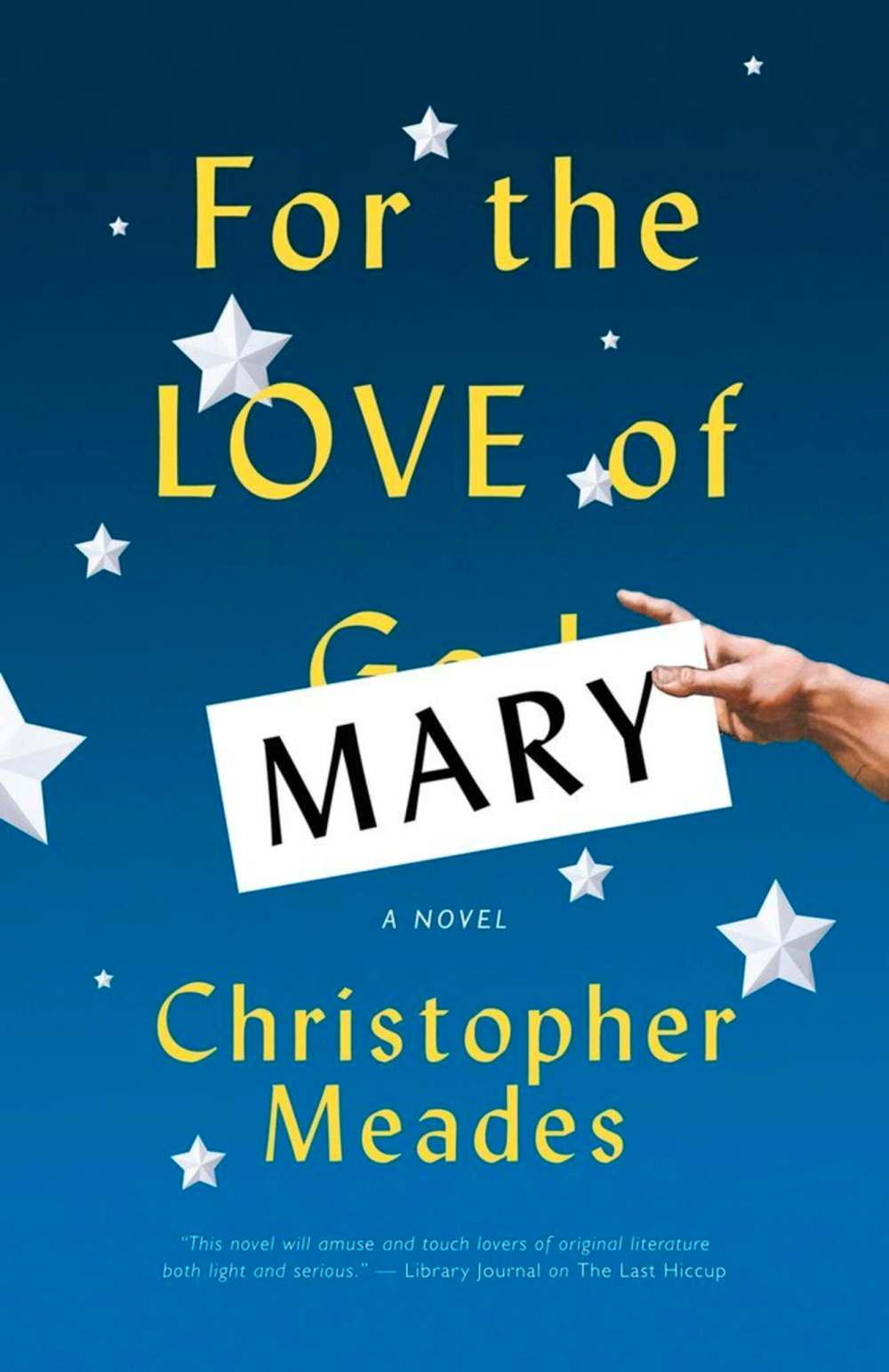

The funniest novels are those that don’t try too hard to be funny: this is conventional writerly wisdom. Also: humour is incredibly difficult to write well. Christopher Meades has bravely ignored both truisms in For the Love of Mary, a coming-of-age satire set in mid-1990s suburbia.

Meades is the author of The Last Hiccup, winner of the 2013 Canadian Authors Association National Award for fiction, as well as 2010’s The Three Fates of Henrik Nordmark and a sizable list of short stories.

For the Love of Mary relies on Meades’ usual panoply of larger-than-life characters and zany set pieces, but they fail to generate much amusement.

This is a pubescent comedy — its narrator is the awkward Jacob, a young man burning with hormones and torturous commitment to family norms. He’s the only vaguely sympathetic figure in the novel: his father, mid-mid-life crisis, has moved into the garage; his mother is a menopausal harpy who denies the family name-brand pancake syrup; and his sister Caroline is a ’90s cliché of the overly sexed surly teenager.

The novel’s main narrative driver is a rivalry between Jacob’s tiny family church and its brand-new rival megachurch that plays out in passive-aggressive church signboard sloganeering. The conflict has something to do with the churches’ stance on Santa Claus, but don’t bother trying to understand it — it isn’t remotely theological. Nobody in the novel seems interested in the differences between Presbyterians and Methodists — which church is which barely merits a mention, and the fact that the author uses the term “mass” to refer to Protestant services signals that even he doesn’t care what actually goes on in any church.

Church-y settings are mere backdrops for Meades’ chief concern — Jacob’s dating foibles as he pursues Mary, the daughter of the rival church’s minister.

Some moments are ripe with potential, such as a relatively deadpan scene in which Caroline takes Jacob and his Cheetos-coated best friend Moss to pick out men’s deodorant that won’t drive the girls away. And scenes where Jacob explores his feelings for Mary ache with some genuine adolescent longing.

But Meades overplays almost every hand. As soon as they appear on the page, characters morph into caricatures: Jacob’s uncle Ted is a dirty uncle, Mary’s boss at Dairy Queen is a bearded lady, and the only East Indian characters in the novel own a convenience store and later don Iraqi fatigues in a re-enactment of Operation Desert Storm. Characters outdo themselves to shriek, fight and take revenge for an ongoing barrage of offences that are as tiring as they are inconsequential.

Meades peppers every page with ’90s references, from metal bands to snack foods and Nintendo games, and while these might trigger nostalgia for millennial-and-older readers, they risk alienating anyone younger.

But the biggest problem with For the Love of Mary is that Meades barely makes an effort to elevate the story above adolescent fantasia. Readers are unlikely to identify with anyone’s crises in this little novel — even Jacob’s, whose fumbling attempts to be a decent person are lost in all the silliness.

Julienne Isaacs is a Winnipeg writer.