Van Gogh or no?: Author posits one of artist’s most famous paintings is a fake

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/02/2017 (3206 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Investigative journalist James Ottar Grundvig, a lifelong fan of Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh, claims one of the master’s works hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is a fake, and he goes to great pains to prove it.

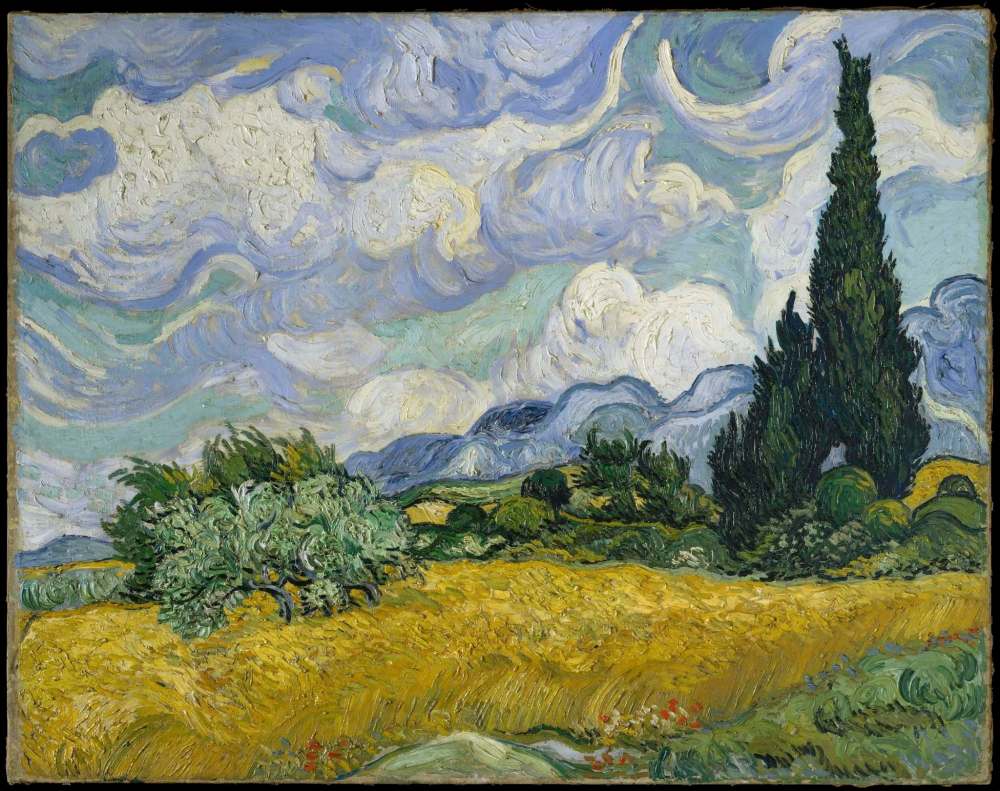

He uses his investigative skills to question the provenance and painting style and materials of Wheat Field with Cypresses in a book that reads like a mystery as he builds layers of evidence that not is all as it should be with the multimillion-dollar painting.

Like a mystery, however, much of the detail uncovered by Grundvig is circumstantial even as it builds toward his assertion. It is missing a key piece to close the case.

Working against him is the fact the Met won’t release the painting’s condition report, which Grundvig asserts will prove it was not indeed painted by van Gogh.

Wheat Field with Cypresses is one of three similar 1889 oil paintings by van Gogh as part of his wheat field series. All were painted at the mental asylum at Saint-Rémy near Arles, France, where he was voluntarily a patient from May 1889 to May 1890. The works were inspired by the view from the window at the asylum towards the Alpilles mountains.

Another, A Wheatfield, with Cypresses, hangs in the National Gallery in London. The third, a smaller painting, is in private hands. The National Gallery has made its condition report public, a report that included “a CSI-like deep-dive investigation to home in on all of the subtle techniques that Vincent van Gogh used,” Grundvig says. It is the van Gogh signature material and techniques that Grundvig feels are missing from the Met painting.

The provenance of this book begins in June 2013, when the author was working on an article for the Huffington Post on fake Jackson Pollock paintings sold to wealthy investors.

During his research he asked art expert Alexander Boyle if there were any fake van Gogh paintings. “Sure there’s one hanging in the Met,” Boyle replied, and the game was afoot.

Even after his July 2013 Huffingtion Post article, Hacking van Gogh: Is the Master’s ‘Fingerprint’ Missing from a Met Painting?, the Met refused to release the condition report.

Grundvig outlines his extensive research, which includes: van Gogh’s correspondence to his brother Theo, an art dealer who stored van Gogh’s paintings shipped from Arles; the size and thread count of van Gogh’s canvases; the special paint colours made just for van Gogh; and sales records of van Gogh’s paintings, which suggest the Met’s painting may been forged by an art restorer.

The author traces the story from van Gogh’s easel to the art forger Emile Schuffenecker, to the collection of a prominent banking family and a Nazi-sympathizing Swiss arms dealer before it is purchased by a U.S. collector as a gift to the Met.

Breaking van Gogh offers a look at the art world of the artist’s time and his struggles in life, at the wartime looting of European art works by the Nazis, at the sometimes-questionable provenance of post-war art sales and at the difficulty in proving authenticity today.

For all his research, Grundvig still uses phrases such as that a Met official “must have known that Schuffenecker was a forger.” That is what you think and say as you are building a case; once you’ve proven that point, you drop the qualifier.

Working in Grundvig’s favour is the fact the Met won’t release the painting’s condition report, which he asserts will prove it was not indeed painted by van Gogh. It’s the old “if you’re innocent, what have you got to hide” argument.

The Met didn’t feel inclined to release the condition report after the initial requests and Huffington Post article. It remains to be seen if a full-length book will reverse that stand. There is a lot at stake, after all.

For now, it appears to be a standoff, but Grundvig and his publisher obviously feel the case has been made for Wheat Field with Cypresses being the work of someone other than van Gogh.

Chris Smith is a Winnipeg writer.