Ringside seat to history

Book relives how one reporter scooped the world on the 1917 Halifax explosion

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/12/2017 (2930 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

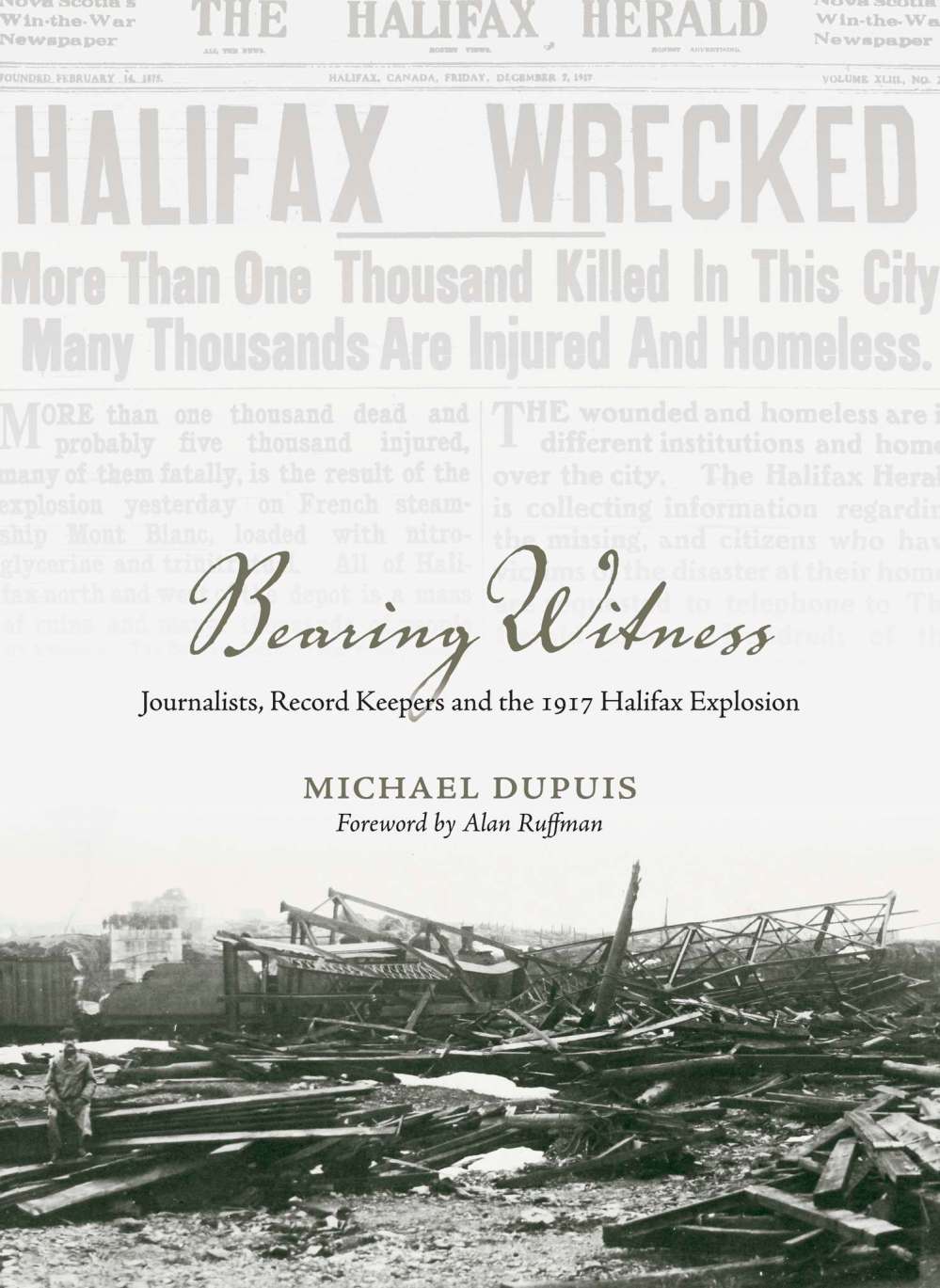

Shortly after 9 a.m. on Dec. 6, 1917, a 2.9-kiloton explosion on board the French munitions ship Mont Blanc rocked the communities of Halifax and Dartmouth. In a 10-square-kilometre area populated by approximately 65,000 people, 2,000 died, most immediately, 9,000 were injured and more than 200 were blinded.

Halifax’s North End resembled a war scene. The blast destroyed more than 1,600 homes and damaged another 12,000. More than 6,000 people immediately became homeless and an additional 12,000 were left without adequate shelter. Gas mains and water pipes ruptured. Railway and streetcar tracks strewn. Debris and human remains covered roads. Trees and telegraph poles splintered.

Halifax Canadian Press superintendent James Hickey scooped all other reporters and correspondents with news of the disaster on Day 1. The following excerpt from Bearing Witness Journalists, Record Keepers and the 1917 Halifax Explosion (Fernwood Publishing), describes Hickey’s actions.

● ● ●

In a special issue on June 20, 1949, honouring Halifax’s bicentennial, Chronicle reporter Graham Allen interviewed James Hickey related to his more than 60 years as a Halifax journalist.

Among Hickey’s recollections was a description of how he scooped all reporters and correspondents in providing the first news bulletin of the explosion to the outside world. The story was headlined: Veteran Newsman Had Ringside Seat for City’s History.

Mr. Hickey believes, and with good reason, that he was instrumental in giving the world its first news of the Halifax explosion in December 1917, half an hour after the disaster occurred.

Like thousands of others, he rushed from his office in the Chronicle Building amid the welter of broken glass. But unlike many, he had a definite plan as a trained newsman. His first idea was to get a taxi to go to the scene of the explosion. But there were none in sight. The streetcars stood immobilized on the tracks.

Then he began to walk towards the North End. He met thousands on the streets, for all had rushed out when the blast came. As he went further north, he met hundreds of women and children crying and bleeding from their wounds, fleeing the devastated area and seeking doctors.

Soon, naval and military men were on the streets warning all to make for open spaces as it was feared the dockyard magazine might blow up. The military men were difficult to pass, Mr. Hickey said, but the bluejackets, after he explained his errand, permitted him to go ahead.

“I went up Cornwallis Street to Gottingen Street and found conditions worse,” he recalled. “The sight was appalling. Masses of humanity were flocking to the Commons. Citadel Hill was crowded, most of the people huddling on the south and western slopes. I talked to many of them.”

Then he rushed down the slope to the telegraph offices, but found them deserted as were stores and offices throughout the downtown section.

However, John Hagen, manager of the Halifax and Bermuda Cable Company, came along the street and Mr. Hickey asked him if there was any chance of getting a message to New York. “We’ll try,” said Mr. Hagen, and, after clambering over some of the debris in the office, he touched a Morse keypad and said, “Yes.”

Then Mr. Hickey stood by Mr. Hagen and dictated the following message:

“Associated Press”

“New York”

“Hundreds killed, thousands injured, and millions of dollars of property damage as result of collision between two steamers in Halifax Harbour this morning and terrific explosion which followed one of the ships said to have been loaded with ammunition. Then fire broke out in ruins and flames raging fiercely with no means to check them. Half of extreme North End of city now levelled.”

After Hickey sent this news bulletin, he went home to find his house damaged and his wife and two of his five children injured. However, he was soon back on the streets gathering information to provide a 2,500-word followup story during the afternoon. His dispatch appeared in newspapers across Canada and the United States.

The Montreal Gazette ran it under the following spreader headline.

Belgian Relief Ship Gored Hull Of Explosive-Laden French Craft Damaged Vessel Caught Fire – 25 Minutes Later Terrific Convulsion Spread Death, Injury and Destruction Over Wide Area – Property Loss Will Reach Millions, Every Structure In The City Being Shaken – One In Each Two Surviving Residents Injures – Temporary Morgues And Hospitals Improvised – Relief Directed To Stricken City From Many Points In Canada And United States

By Canadian Press — Halifax, N.S., December 6 — As the result of a terrific explosion aboard a munition ship in Halifax harbour this morning a large part of the north end of the city and along the waterfront is in ruins and the loss of life appalling…

Chief of Police Hanrahan tonight estimates that the dead may reach 2,000. Twenty-five wagons loaded with bodies have arrived at one of the morgues.

Among the dead are the fire chief and his deputy, being hurled to death when a fire engine exploded. Fire followed this explosion, and this added to the greatest catastrophe in the history of the city.

All business has been suspended and armed guards of soldiers and sailors are patrolling the city. Not a street car is moving, and part of the city is in darkness. All the hospitals and many private houses are filled with injured.

The offices of the railway station, the Arena rink, military gymnasium, sugar refinery and elevator collapsed, and injured scores of people…

The collision between the two steamers occurred near the point of the harbour known as Pier 6, and was between a French munitions ship, the Mont Blanc and a Belgian relief ship, the Imo…

At nine o’clock this morning, the city was enjoying its usual period of calm, the street were crowded with the usual number of people who were wending their way to work. Then came an explosion. From one end of the city to the other glass fell and people were lifted from the sidewalks and thrown to the pavements. In the downtown offices, just beginning to hum with the usual day’s activity, clerks and heads alike cowered under the showers of falling glass and plaster which fell about them…

The main damage was done in the north end, known as Richmond, which was opposite the point of the vessels’ collision.

Here the damage is so extensive as to be totally beyond description. Street after street is in ruins and flames swept over the district…

A few minutes after the explosion occurred, the streets were filled with terror-stricken people trying to make their way as best they might to the outskirts, in order to get out of the range of what they thought to be a German raid.

Women rushed terror-stricken through the streets, many of them with children clasped to their breasts. In their eyes was a look of terror as they struggled on with blood-stained, horror-stricken faces, endeavouring to get anywhere from the falling masonry and crumbling walls.

By the littered roadsides as they passed, could be seen the remains of what had once been human beings, now torn and mangled beyond realization of what had occurred.

Here and there lay the cloth-wrapped bodies of children, scarred and twisted by the force of the horrible explosion.

By the side of many of the burning ruins were women who watched the flames as they consumed the houses which in many cases held the bodies of loved ones. With dry eyes they watched their homes devoured by the flames, and as others passed with inquiries as to whether they could render aid, they shook their heads in a dazed manner, and turned their gaze once more to the funeral pyres.

Michael Dupuis is a retired history teacher, writer and author. His story, Fallout from 1917 Halifax Explosion reached all the way to the Prairies, appeared in the Free Press on Jan. 12, 2012. In 2014, he published Winnipeg’s General Strike: Reports From The Front Lines. He can be reached at michaeldupuis@shaw.ca