Quite the trip

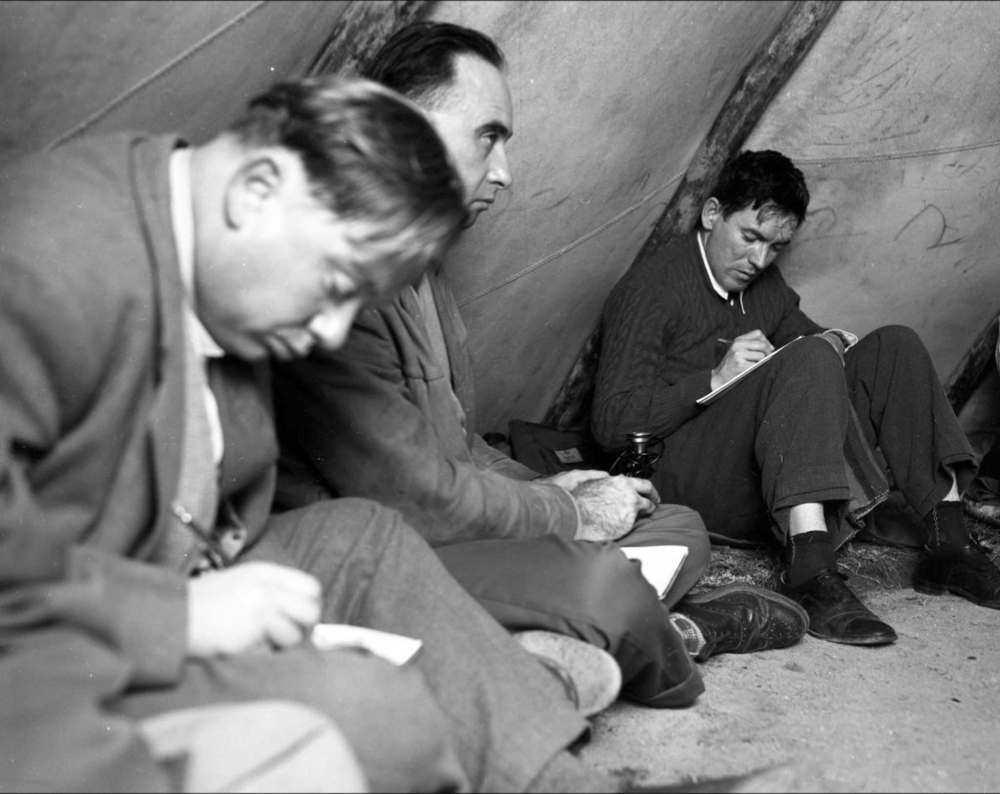

Trio of Saskatchewan researchers explored potential benefits of LSD

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/07/2018 (2737 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Football rivalries aside, the Prairies often exude a bland placidness. It may be surprising, then, that in the 1950s and ’60s Saskatchewan was an internationally renowned research centre on hallucinogens, especially lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD.

In his first full-length book, Saskatchewan author P.W. Barber investigates the scientific and cultural histories of psychedelics in research and therapy over a decade’s span. Lurid cover aside, Psychedelic Revolutionaries is a sober, richly-detailed account, replete with just over 900 endnotes.

If not as familiar as Timothy Leary, the names of Humphry Osmond, Abram Hoffer and Duncan Blewett put Saskatchewan, for a time, at the forefront of LSD research. It was Osmond who coined the term “psychedelic” to describe the effects of hallucinogenic substances. Psychiatrists Osmond and Hoffer and psychologist Blewett were principally interested in how LSD could help explain the architecture of the mind and influence its therapeutic treatment.

Early interest in LSD centred upon its apparent ability to mimic psychosis. Researchers were keen to learn what it might demonstrate about both the treatment and experience of severe mental illnesses. Furthermore, the distorting perceptual effects of LSD were employed to understand how patients might perceive then-abysmal hospital settings, and thus improve patient care.

Identifying structural similarities between adrenaline and mescaline, another psychedelic, Osmond and Hoffer argued that adrenal metabolism dysfunction caused schizophrenia. Such a view challenged prevailing psychoanalytic approaches, suggesting radically new treatment avenues.

Osmond, Hoffer and Blewett also experimented with LSD as an alcoholism treatment. A significant public health concern in Saskatchewan, the conceptualization of alcoholism was shifting from moral failure to medical disease. Initially employed to scare patients into sobriety, treatment soon moved in a different direction, whereby single large doses of the psychedelic provoked profound experiences, often described as transcendental or revelatory. Buttressed with clinical supports, LSD initially proved wildly successful.

Unsurprisingly, psychedelic research was controversial, partially rooted in the rise and fall of counterculture movements of the 1960s and ’70s. More damning to Osmond and Hoffer’s work were methodological issues and the inability of other researchers to replicate their results, though the question of how faithful these attempts were persists.

The effects of LSD are so pronounced that double-blind experimentation proved nigh impossible. This, along with their use of personal impressions and patient narratives, led to condemnation of their work as pseudo-science. Barber does a marvellous job of humanizing research: what underscored the arguments, on both sides of the issue, was not simply the search for truth, but career and social aspirations, petty personal grudges and inabilities to cede ground.

If the scientific ground upon which Osmond and Hoffer stood grew increasingly unstable, it was ultimately the cultural milieu of the 1960s that spelled the end of their work. Widespread use of LSD by the middle class was quickly perceived as a threat to social order. Opinions on psychedelics polarized, with evangelists Leary and Ken Kesey on one side, and much of the broader medical and political bases on the other.

Osmond and Hoffer sought a middle ground — promoting the value of psychedelics in research and perhaps, within tightly regulated contexts, for personal growth — but were ultimately marginalized. In the end, LSD became sole province of the black market, and scientific and therapeutic use ceased.

Psychedelic Revolutionaries is a remarkably detailed accounting of a period in Canadian research history long obfuscated by larger cultural forces. If Barber resists the urge to side with any one camp, it is because the histories he sketches involve questions which today are largely unanswered. Recent thawings in the relation between psychoactive substances and therapeutic treatments and research may eventually help determine precisely how revolutionary Osmond et al. were, and what value their research offers today.

Jarett Myskiw is a retired fence builder.