Dangerous decisions

Adiga's latest novel highlights plight of refugees in Australia

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/03/2020 (2021 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

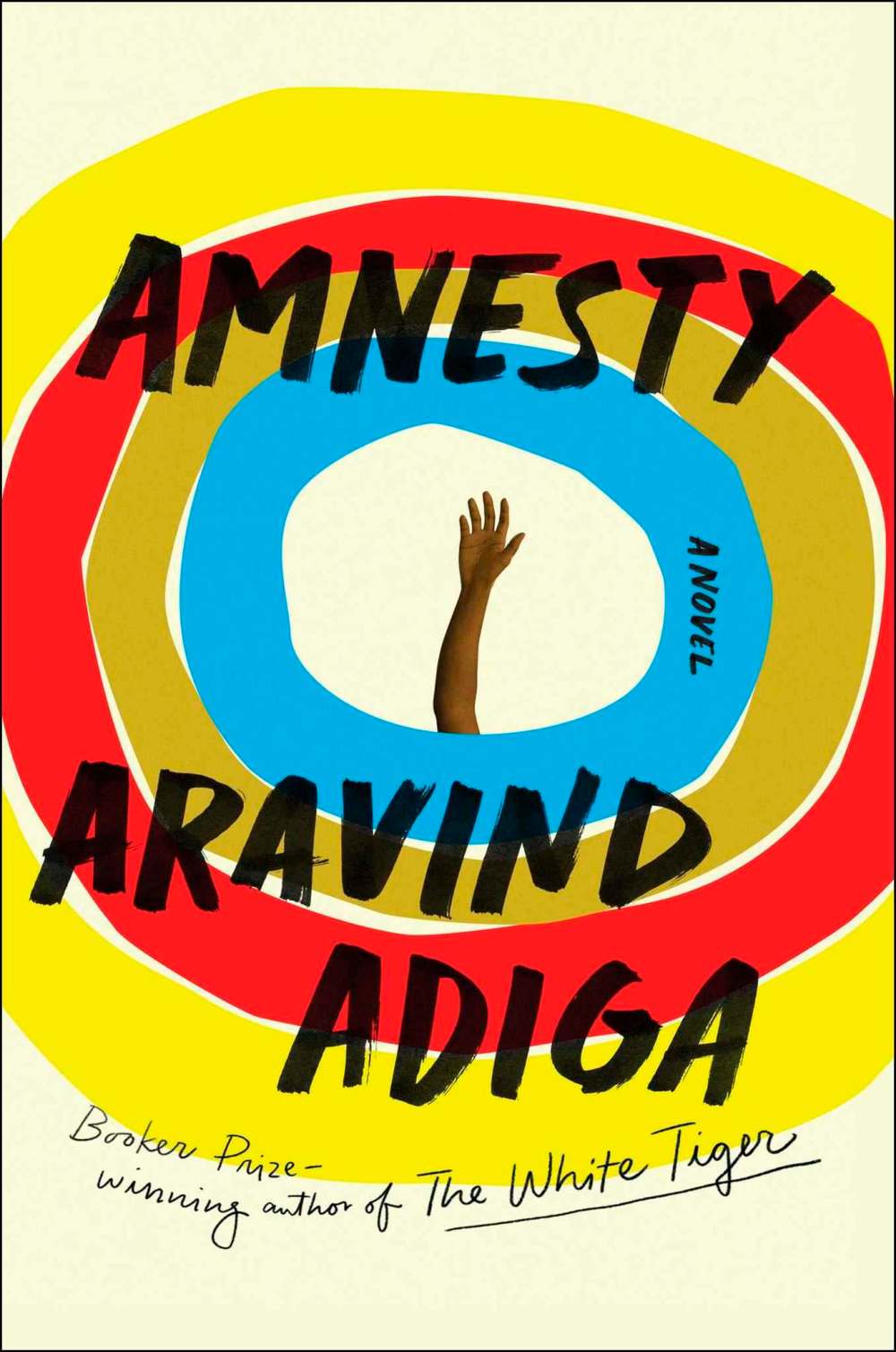

When Indian novelist Aravind Adiga’s first book, The White Tiger, won the Booker Prize in 2008, he became an instant celebrity, and for good reason: the novel fibrillates with manic and febrile energy as Adiga takes his protagonist, Balram Halwai, on a wild ride from his life as a village boy to the heights of entrepreneurial (if sleazy) success in a globalized world. The novel reads like a pithy amalgam of Slumdog Millionaire with The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, with more substantial ethical underpinning than the former and more spectacular narrative pyrotechnics than the latter.

In this, his fifth book, Adiga has focused his formidable talent on another pressing contemporary theme: refugees and illegal immigrants, the world’s seething and growing multitudes of the displaced, now estimated at some 71 million. Adiga situates his dissection of dispossession in Sydney, in a blatantly racist white Australia that oppresses and exploits its burgeoning underclass in every imaginable way.

Like The White Tiger, Amnesty concentrates its narrative tactics on one character — here, Dhananjaya Rajaratnam, or “Danny” as the Aussies mindlessly dub him, a Tamil from Sri Lanka who has fled to Australia originally as a student but has quickly submerged himself in the country’s vast subculture. He has become one of the millions of “illegals,” a furtive housecleaner always on the lam, one eye out for Aussie officialdom, the other out for the next Aussie — or legal immigrant — who will try to trample him underfoot. The narrative is further animated by the insistent internal rhythms of Danny’s paranoia, complemented by and inseparable from his external reality, his identity increasingly atomized as he dodges Sydney’s cops and traffic and gawks at its brutalist architecture.

The pulse of Adiga’s wired narrative is further jacked up by two elements: first, like a latter-day Ulysses, this novel takes place in one day, with the time continuously foregrounded by very short “chapters,” each entitled with a time of day, e.g., “12:03 p.m.,” “1:16 p.m.” and so on. Second, Danny discovers that he has become aware of the identity of a probable murderer when one of his housecleaning clients is discovered stabbed to death and submerged in a creek.

What to do? If he calls the cops, he himself will be revealed as an illegal and instantly deported; if he remains silent he becomes complicit, at least in his own eyes. His girlfriend Sonja — yet another immigrant in this culture — cannot save him; and the little cactus he has carried around for her all day long ultimately serves a less loving but more ironically shambolic end when he hurls it at the presumed killer.

There is a larger game afoot here: through Danny’s dilemma Adiga probes the ethical morass not only of the official racist culture, but of layers of the subcultures. The murderer is a thuggish and adulterous “legal” Indian who has his own set of racist and moral failings, while he and his victim — both addicted gamblers and philanderers — entertain themselves by patronizing Danny, who was himself tortured by Sri Lankan authorities when he returned home from Dubai, where he had fled in his first attempt at escape from the impossible conditions in his homeland. Now in Australia, he must survive by his wits and his wiles — a survival increasingly imperiled as the day unfolds and the killer persecutes Danny with an endless series of calls Danny reluctantly takes on his battered cell phone.

For Danny, there is no hopeful ending, but that must not be revealed herein. You must read Amnesty for any (provisional) hope of it. Or, more accurately: like many good novels, Amnesty re-imagines, inescapably, a dire part of our reality so that readers can neither shirk their complicity nor claim ignorance of its consequences.

In an attempt to save himself, Neil Besner reads and writes about good fiction.