Drawing on the past

Tomine's autobiographical comic a poignant, moving exploration of life as an author, father and husband

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/08/2020 (1906 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The 1962 film The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (based on a short story by Alan Sillitoe) was part of the British “angry young men” movement of working-class outsiders rebelling against a rigid class system. Adrian Tomine’s thoroughly entertaining and surprisingly tender autobiographical comic, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, riffs on this title, but the protagonist is more self-deprecating than angry, and by the end his loneliness has been alleviated in a beautiful depiction of love for his wife and daughters.

Book review

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist

By Adrian Tomine

Drawn & Quarterly, 168 pages, $35

Tomine is a celebrated fourth-generation Japanese-American cartoonist and illustrator whose work conveys the deep currents of emotion running underneath seemingly banal everyday experiences. Born in California and based in New York, his career started with a self-published minicomic, Optic Nerve, that was picked up by Montreal’s Drawn & Quarterly and published as a complete collection in 1998.

Over the past 15 years, Tomine has become an acclaimed graphic novelist and illustrator. Shortcomings (2007), Scenes from an Impending Marriage (2011), Killing and Dying (2015) and now The Loneliness of a Long-Distance Cartoonist are all on their way to becoming classics of American cartooning, if not literature more generally. Tomine is also a commercial illustrator; his recent cover for the New Yorker of a masked and gloved COVID-19 hospital worker waving goodnight to her family on her phone has become one of the early defining images of the pandemic.

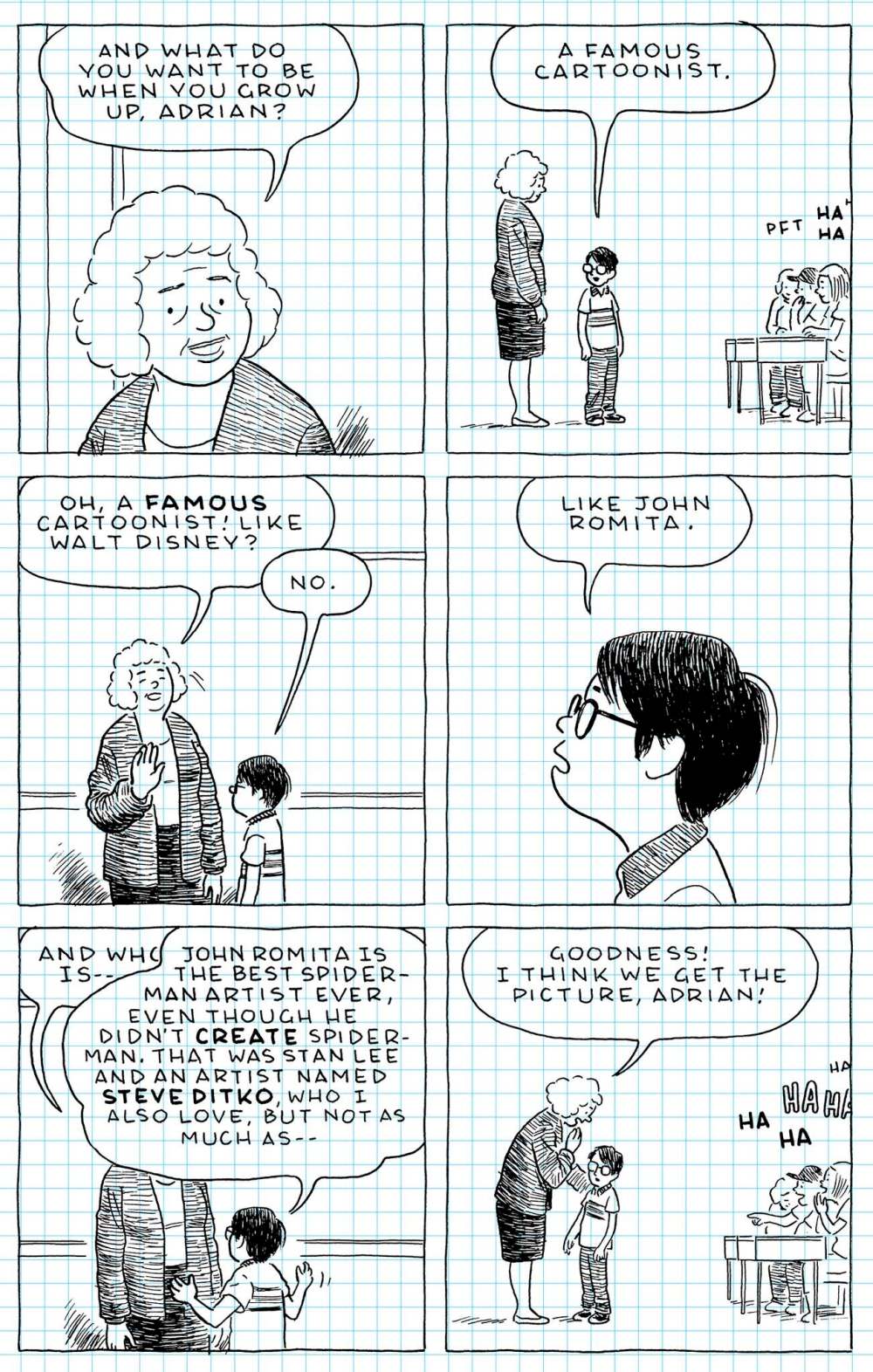

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist presents a series of anecdotes about the artist’s life, from early struggles for recognition to the awkwardness of relative fame in the comics world to a final recognition that love for his family matters more than his professional ambitions. Drawn in black ink on blue-lined graph paper in a regular, clean grid of large panels, it has a sketchbook aesthetic in contrast to Tomine’s usually more colourful, complex layouts.

Appearances can be deceiving, though, as this is a highly crafted graphic autobiography in which Tomine constructs himself as the artist whose life on the road at signings, comic cons and industry events is much more emotionally draining than actually making art.

Tomine is a master cartoonist, and each panel is a lesson in composition, body language and comics’ ability to depict both dialogue and the protagonist’s interior monologue. As well, each anecdote is impeccably structured to deliver a punch line, insight or twist at the end, reminding us that Tomine is as much a writer in the American realist short-story tradition as he is a superb cartoonist.

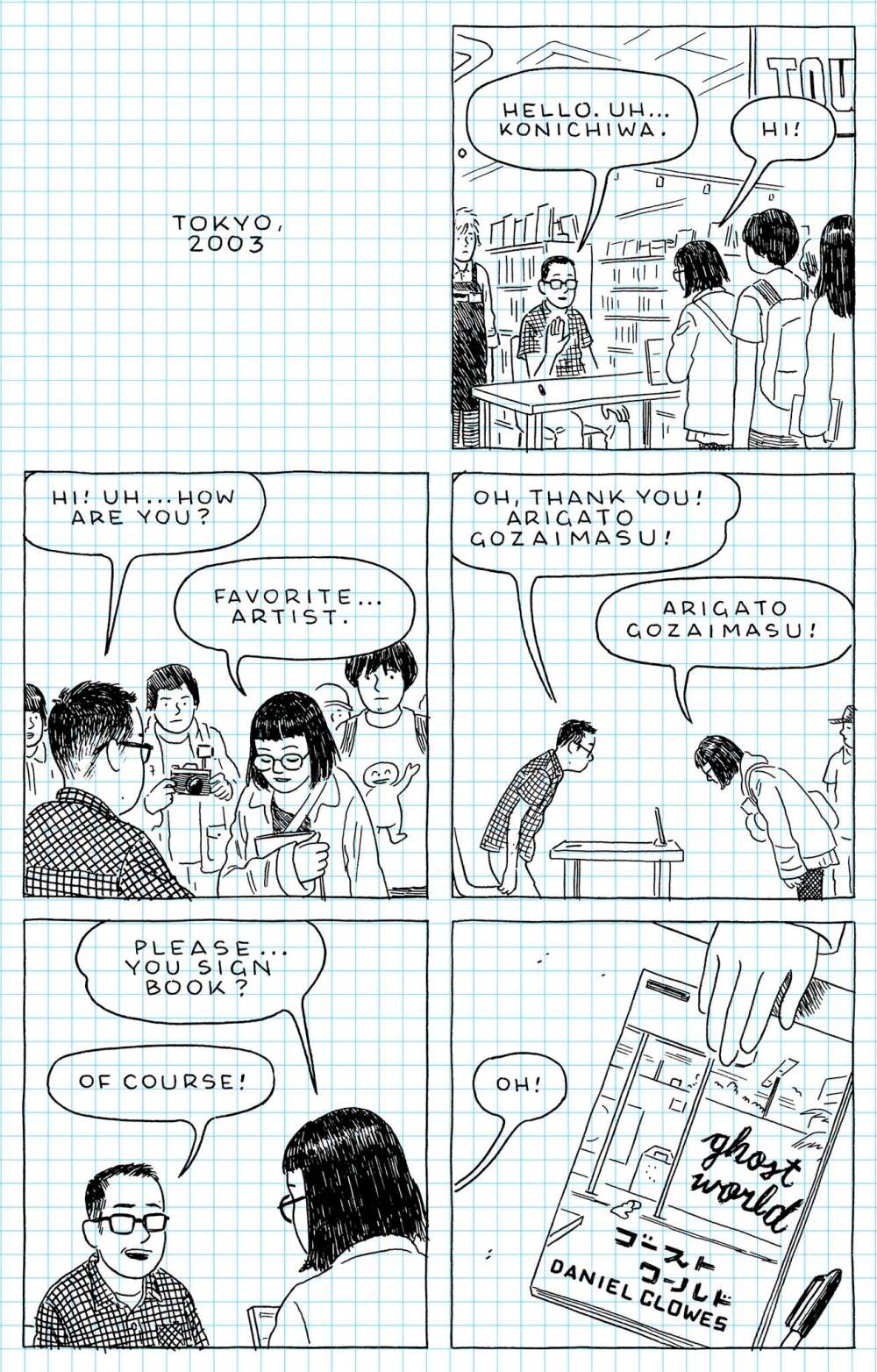

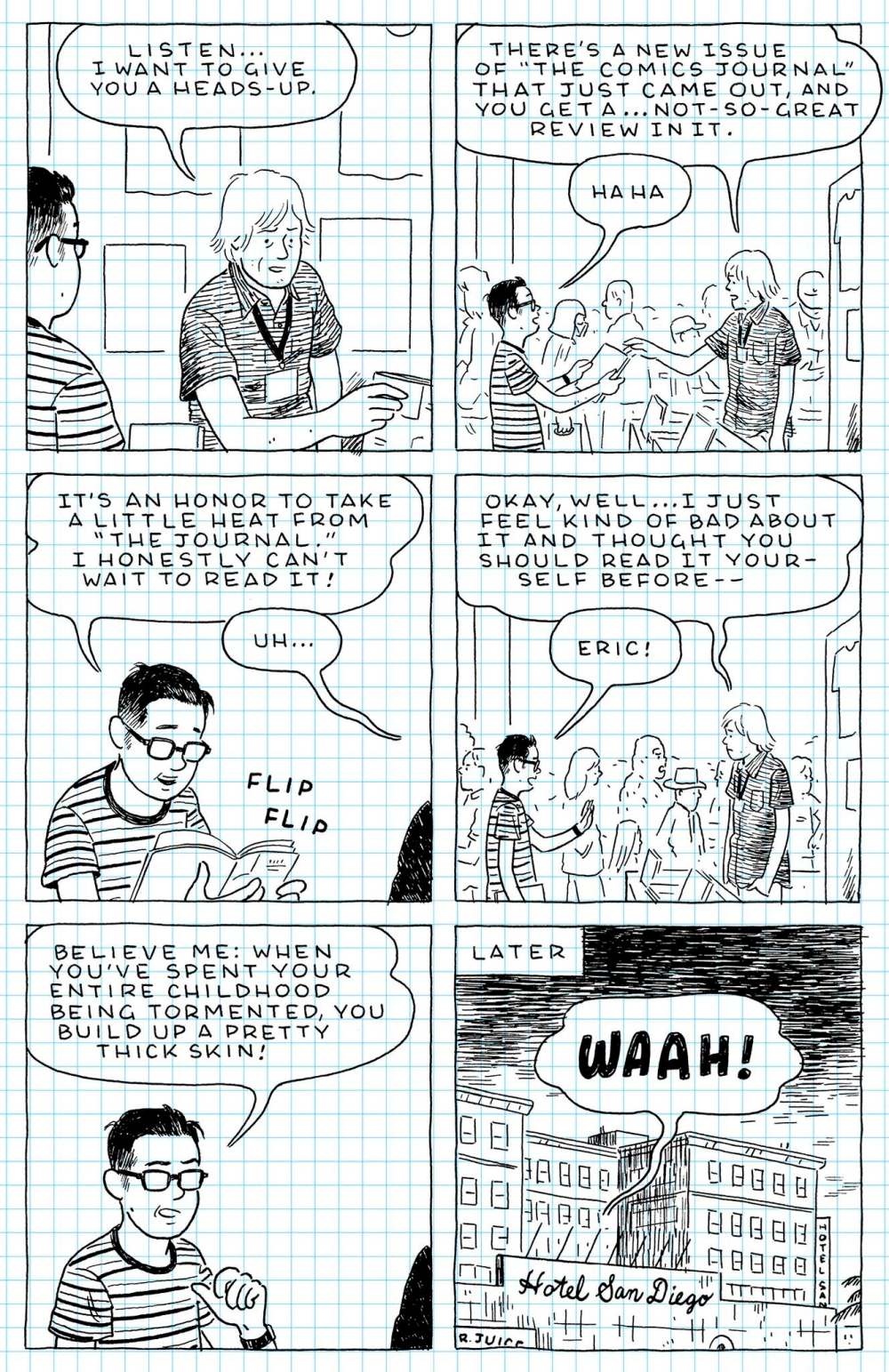

You don’t need to be a comics fan to get most of this book, and even when specific figures become running jokes — Tomine is constantly overshadowed by authors Neil Gaiman and Daniel Clowes — the context is very clear. Indeed, many of the awkward situations are painfully familiar: he’s bullied at school for being a nerd; he pretends he can take criticism but when he reads a negative review in private he falls apart; he has to deal with intrusive strangers while his toddler is having a very public meltdown; and, in perhaps one of the most memorably painful anecdotes, he has a lactose-intolerant-related episode of explosive diarrhea on a first date.

As the story progresses and Tomine becomes more famous, the awkward situations become more specific to the celebrity culture of alternative comics, but also relatable to anyone who has attended a literary event. In the Q&A after one reading, an aggressive and pretentious (but handsome, as everyone agrees later) man attempts to deflate Tomine’s reputation. In another anecdote he has a creepy fan stalker, and when Tomine confronts him, the man responds with a racial epithet.

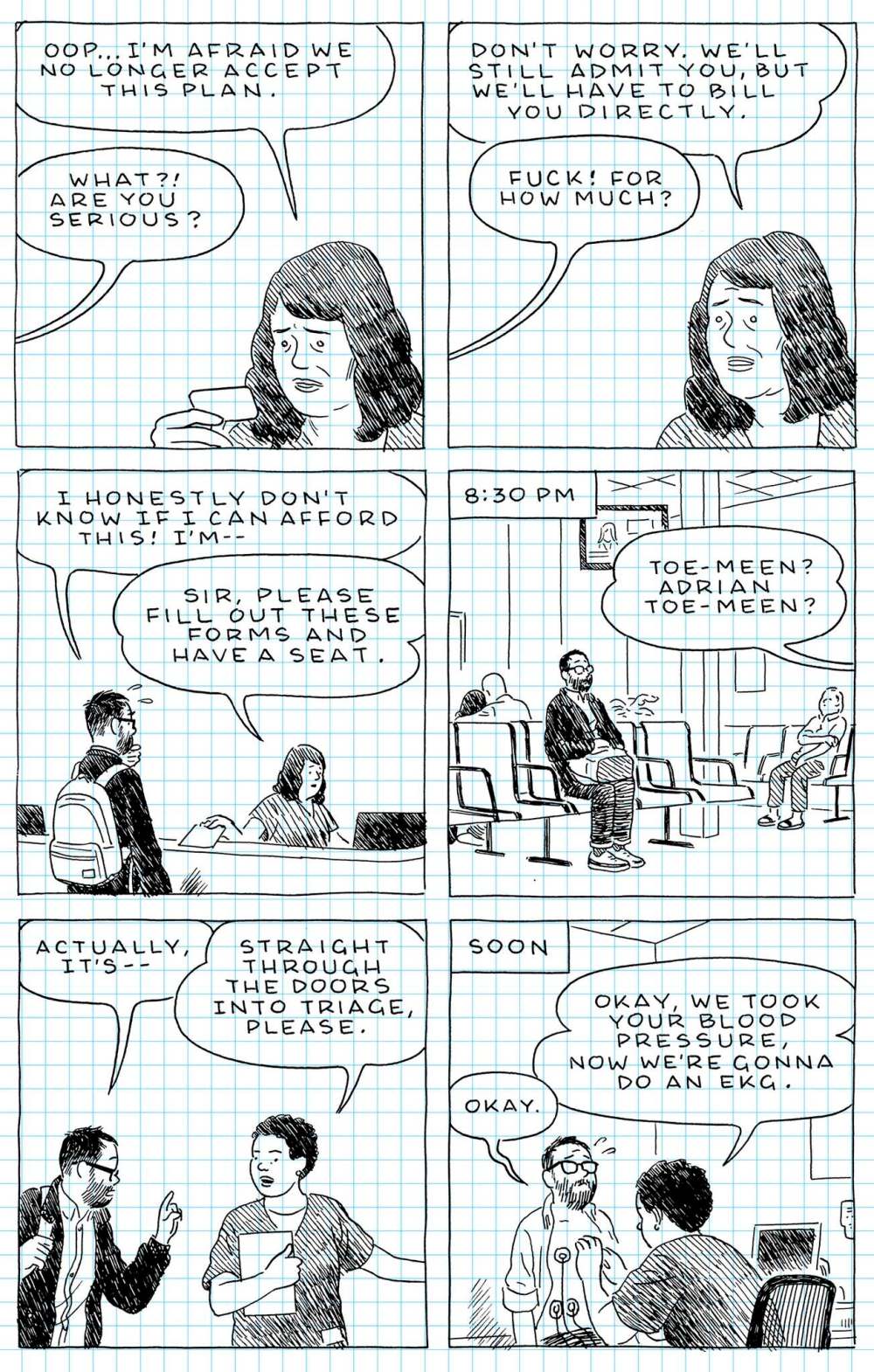

This is one moment when Tomine’s outsider status as a Japanese-American cartoonist in a largely white industry comes to the fore — although, as in his other works, Asian-ness and race in general are represented in visuals or dialogue and without narratorial comment. The embarrassing running gag — that no one knows how to pronounce his last name correctly (TO-meen-uh), nor are they interested in learning — is another way he subtly illustrates his alienation from this dominant white milieu.

This book is really funny at points, but it avoids indulging in the alternative comics trope of the lonely male loser dwelling in his misery. In the final section, Tomine shifts from the life of the professional cartoonist to an episode where he thinks he is dying. In the emergency room, he pens a moving letter of gratitude to his two daughters, reproduced in the book.

The story ends with Tomine admitting to his sleeping wife that his main memories of being a cartoonist “are the embarrassing gaffes, the small humiliations, the perceived insults,” rather than the satisfaction of the work itself or his growing critical acclaim.

This final epiphany that his love for his wife and daughters has given him true joy elevates The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist to a profound meditation on the relationship between creativity, work and fulfillment.

Candida Rifkind is professor in the Department of English at the University of Winnipeg, where she teaches and researches comics and Canadian literature and culture.