Deep freeze

19th-century Antarctic voyage chronicled in riveting, chilling detail

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/08/2021 (1563 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Isolation, illness and even madness might feel a little too close to home after 18 months of COVID-19.

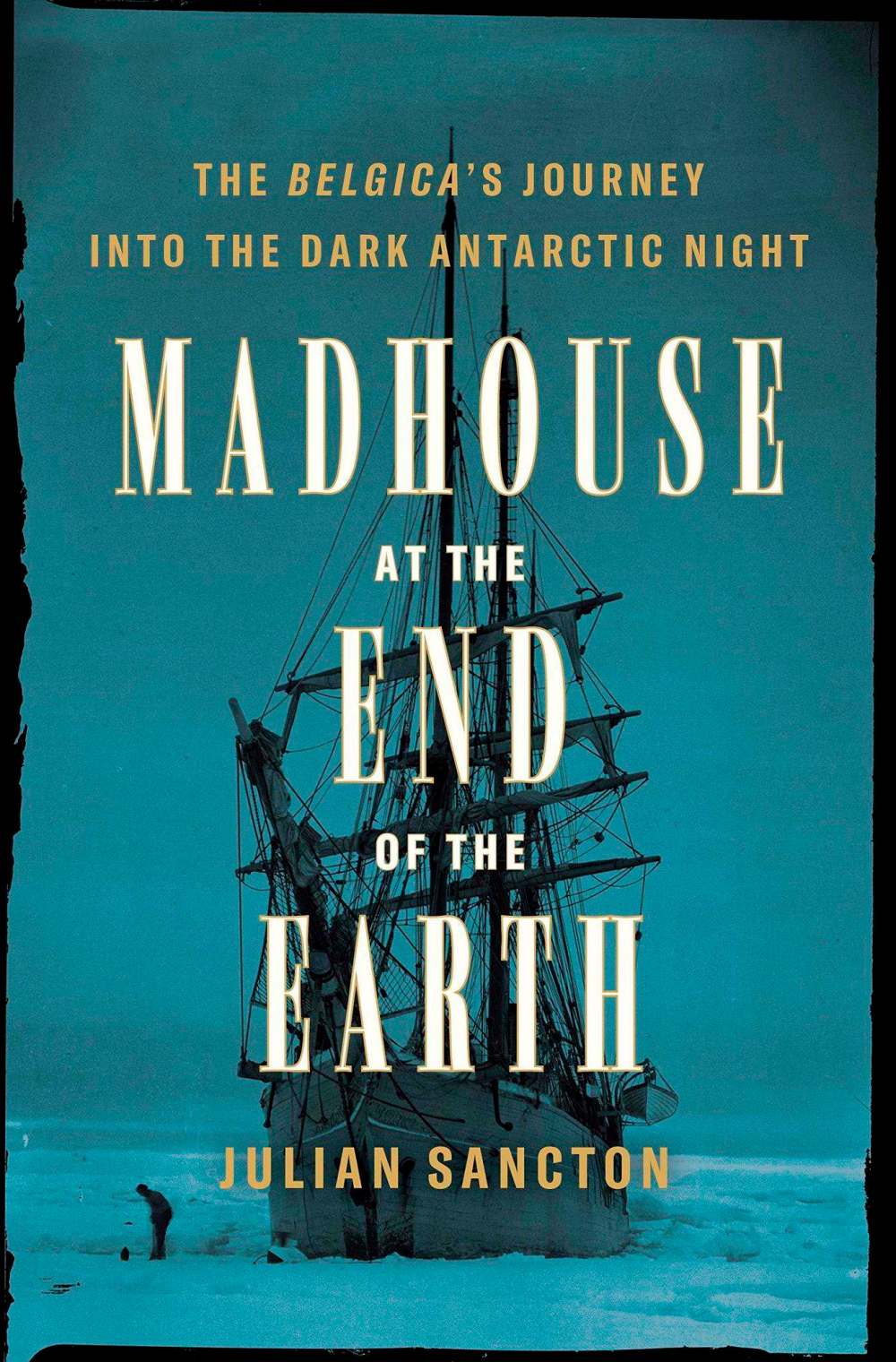

Nevertheless, Julian Sancton, editor for Departures magazine and contributor to Vanity Fair and Esquire, among other publications, manages to relate a thoroughly engaging, well-paced story of hardship and tenacity in Madhouse at the End of the Earth. This true account of Antarctic survival is a fiercely gripping page-turner.

The Belgica, a Norwegian-built steam-powered ship, left Antwerp in 1897 under the command of Adrien de Gerlach. Gerlach was an ambitious 31-year-old from an aristocratic Belgian family, eager to prove himself worthy of his name. He commanded a ship crewed by an eccentric, often-changing cast of sailors and researchers headed toward an Antarctica that, at the time, existed more in imagination than fact. From the planning stages of the mission until its eventual return, the Belgica never drifted far from calamity.

Alongside Gerlach were two figures who had not yet achieved the infamy and acclaim, respectively, that they would soon be accorded: physician Frederick Cook and explorer Roald Amundsen. There was also the nearly indefatigably loyal Georges Lecointe, a surly, often-violent cook and a motley array of researchers and sailors. The Belgica’s crew, breaking longstanding tradition and popular expectation, was international in composition.

The ship’s mission was multifaceted: to push further south than any previous voyage, to map uncharted lands, to catalogue plant and animal life in the Antarctic and to study meteorological phenomena. Desperate to avoid a shameful early return without having achieved its objectives, the Belgica became trapped in the inexorable crush of Antarctic pack ice in March 1898. For a year, the crew waged a tenuous battle for survival; it was not only lack of food and shelter or the threat of the ship’s destruction, but a variety of physical and mental illnesses which progressively weakened the crew’s morale.

Yet among the tragedy, there are moments of humour and astounding bravery. Sancton captures the dreary monotony of an all-day sun (or all-day darkness), of tedious routine and unrelenting anxiety, without losing pace or verve.

Sancton’s storytelling shines particularly bright as he traces shifting interpersonal alliances. There were three principal poles around which these relationships rotated: nationality, ambition and social class. The degree to which each divided or united the crew shifted in response to conditions on the water or in the ice.

Beyond frequent acts of insubordination and the threat of mutiny, there is the enduring friendship of Cook and Amundsen, which bookends the entire tale. These episodes of humanity, whether cunning or caring, of sacrifice or exploitation, give Madhouse at the End of the Earth its narrative centre.

For all its tragedies, the Belgica was able to accomplish a surprisingly long list of objectives in Antarctica before getting free of the pack ice in February 1899, to which Sancton gives due attention. At its heart, the journey comes to be less about exploration or science and more about the interconnected desires, of pride and ambition, that lay in the hearts of de Gerlach, Cook, Amundsen, and Lecointe.

Sancton draws from a wealth of historical research and primary documents to vividly depict not only what each member did during those dark days, but what they, in their innermost thoughts, felt, feared and dreamt.

Stories of adventure and survival appear to have captured the public’s interest of late, if not quite to the extent that they animated popular consciousness during Gerlach’s time. Perhaps we all need vicarious adventure and heroism, especially as our world has shrunk with COVID-19.

While it doesn’t trace an adventure quite so epic, nor nearly so well-remembered as Ernest Shackleton’s exploits on the Endurance, Madhouse at the End of the World is a worthy entry into a storied body of literature.

Jarett Myskiw is a teacher in Winnipeg.