Short fictions mine the mundane and bizarre

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/08/2021 (1538 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

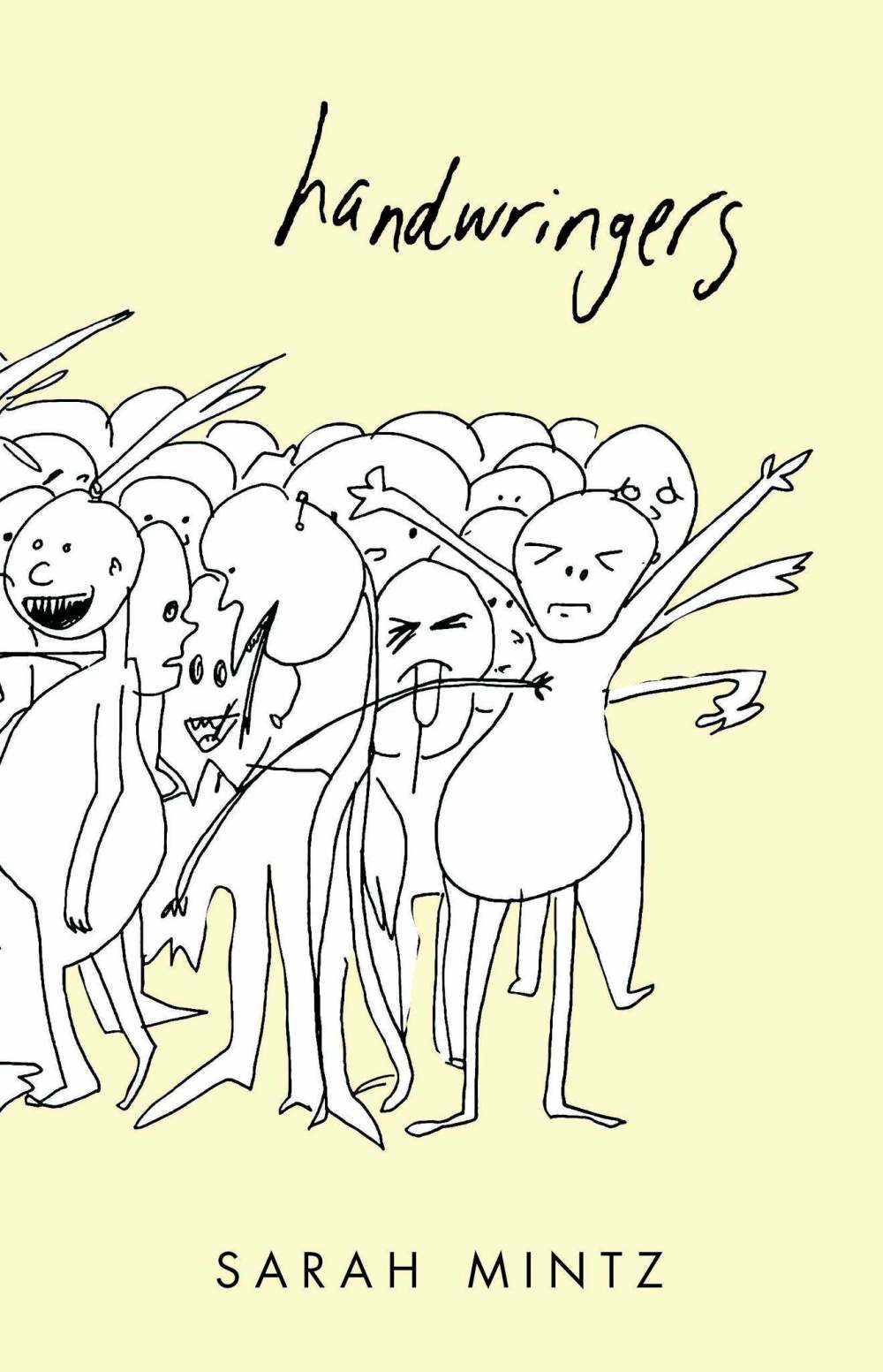

Sarah Mintz is a young writer who uses her Jewish background viewed through a contemporary lens as the overarching theme in her slim book of short stories, Handwringers.

Having recently finished the University of Regina’s English graduate program, Mintz has combined some of the writing she did as a student with new content for her collection. Her stories, which vary in length from a paragraph or two to a few pages, reflect her personal experiences and thoughts about Jewish folktales and culture as well as North American popular culture. Some are highlighted with small pen-and-ink caricatures of that story’s main character, drawn in a grotesque style.

The overall tone of the story collection is slyly humorous. In The Door on Your Way Out, a dead grandmother’s spirit returns to her family’s home in the winter and asks for a glass of water. She then complains that her daughter has added ice cubes without first washing her hands and refuses to share any information about the afterlife.

“‘How long can you stay,’ I asked.

‘Stay,’ Nana said. ‘I just came for the water. I was thirsty, nu.’

‘Okay Mama,’ my mother said. ‘Well, I want you to know that we love you very much.’

‘Of course you love me,’ Nana said. ‘It’s easy to love me now,’ she laughed to herself rather meanly.”

After the grandmother disappears, the granddaughter is sure that the dead woman curses her, as she’s not had a date since that time.

In till the end, Mintz writes about a woman experiencing the end of the world, but who takes time to dress nicely and do her makeup before leaving to face the destruction.

A woman who is taking Hebrew lessons from a rabbi, whom she wants to seduce, has her plans foiled when the rabbi discovers a half-eaten Chinese pork bun in her purse in the aptly-titled story PIG MEAT.

Riffing on an early 1990s Corn Pops commercial in Sponsored Contact, Mintz writes about the revenge that a young girl enacts after her older brother’s girlfriend pours the last pieces from a box of cereal into her bowl.

“Ghlotto thlove chlose Popfs,” the sister splutters with her mouth crammed full of the cereal she retrieved when the girlfriend stormed out.

In Street Trash, a young girl watches as passersby on a busy sidewalk ignore an injured pigeon. She walks to the police station to report the injured bird, asking for permission to stomp on the bird’s head to kill it. She can tell that the police don’t take her seriously, but when she goes back to check on the now-motionless pigeon, she sits nearby waiting for the police to arrive.

Mintz is able to find a story in many of life’s everyday occurrences, and create others that are somewhat bizarre. She views these incidents through her Jewish culture, folklore and traditions, producing a unique take on life as shown in handwringers.

Andrea Geary is a Winnipeg freelance writer.