Cuban drug-runner’s fortunes built on suffering

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/02/2022 (1331 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

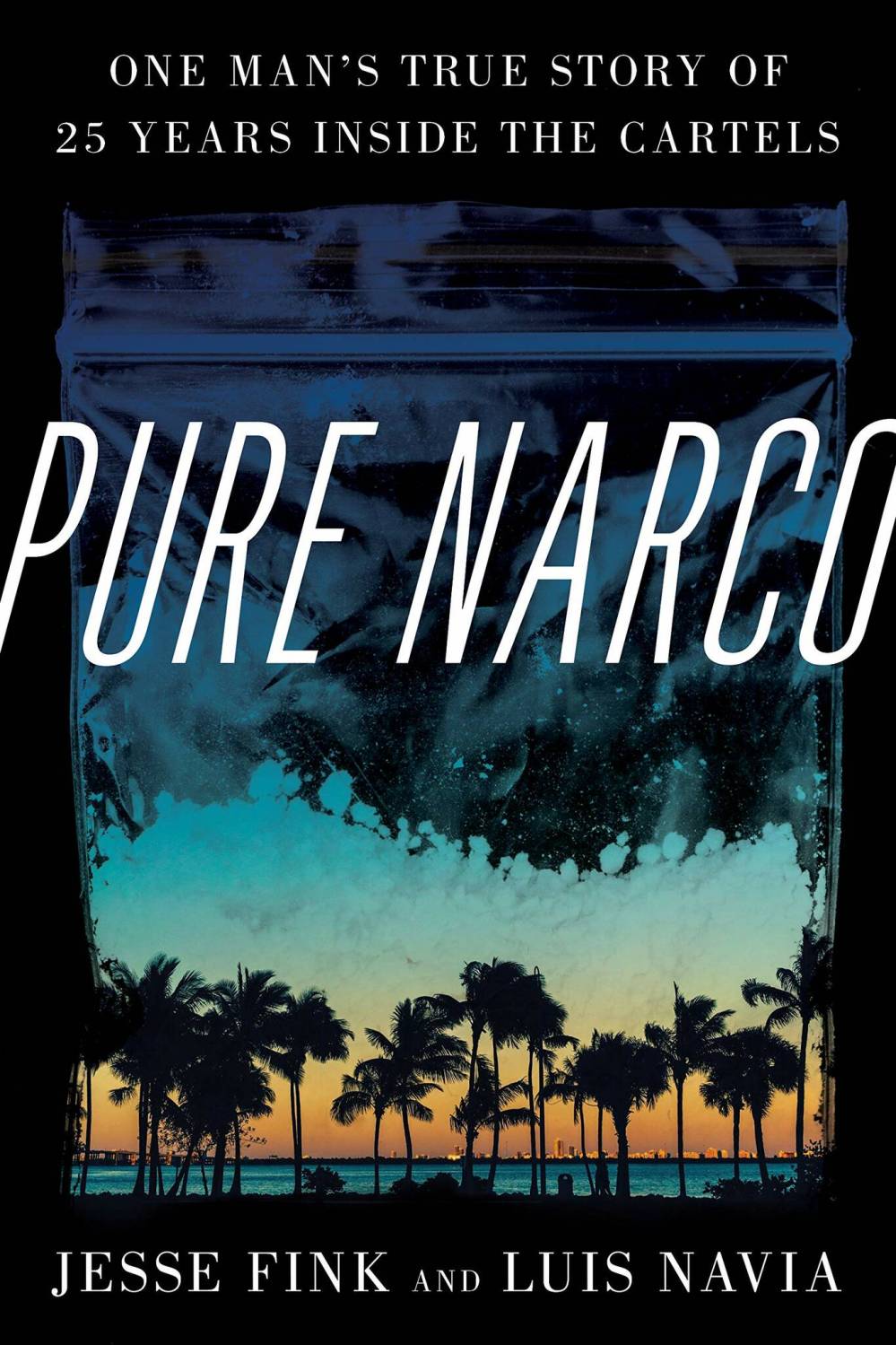

This biography/autobiography is a detailed look at Luis Navia’s 25 years working for the deadliest Colombian and Mexican cartels as a pure narco, a drug smuggler only, which allowed him to escape the ever-present violence and death that marked the international cocaine trade.

That he is now able to live a good life in Florida after being captured by U.S. drug enforcement agencies, giving evidence against the cartels and serving only a short jail sentence, is further evidence of his skills at reading dangerous situations and avoiding violence, and his incredibly good luck.

The book is a mixture of autobiography — Navia’s story in his own words — and biography, including Fink’s research on cartel operations and interviews with family, friends and drug enforcers involved in the 12-nation Operation Journey that brought down Navia and many bigger players in 2000.

As international drug traffickers don’t keep diaries, the book is largely based on Navia’s recollections and, as Fink explains, Navia maintains the account “is true, but is not to be taken as definitive.”

Navia was born into the privileged life of Cuban high society. His family fled Castro’s revolution and relocated in Florida, where his father continued to do well in the sugar trade. Navia could have joined the family business after university, but a stint at Georgetown University where he sold drugs to fellow students set him on a quarter-century path of smuggling “200 tons easy” of cocaine to the United States and later Europe.

After leaving university, Navia became involved in the wild west of 1970s drug trafficking in Miami, fuelled in large part by the influx of Cubans exiled by the Castro regime, a group that included many young criminals with little to lose (reference the movie Scarface).

He was selling a few grams before falling for a woman with connections to the Medellín Cartel and becoming an expert smuggler specializing in logistics. He easily settled into a life of prostitutes and sampling the wares he was transporting.

Navia’s protestations that he didn’t take part in the rampant violence dished out by sadistic cartel killers — that he was just delivering the product — ring hollow.

The 66-year-old admits he doesn’t “have the highest regard for human life.” The gruesome violence didn’t disturb him; for example, he didn’t let the sight of someone being waterboarded before getting “two in the head” distract him from his lunch.

Yet, Navia also claims he was a hapless Mr. Magoo figure, “a normal father and a very loving dad” whose calling card was his refusal to carry a gun. That allowed him to walk out of the criminal underworld alive (he talked his way out of three kidnappings and was almost fed to crocodiles). “Non-violence is a very powerful weapon,” he says. “It’s like that Gandhi s—.”

The former drug smuggler shows no remorse or guilt for his role in a trade that has meant misery for so many addicts. He made millions of dollars, spent the bulk of it, but still has money in offshore accounts. He runs a construction business in Miami, consults with federal enforcement agencies and lives a good life that includes an ongoing relationship with two of the American drug enforcement agents who arrested him and shepherded him through the plea deal that allowed him to serve a short sentence and ease into a new life.

Australian-based Fink, the author of five books, including bestselling biographies Bon: The Last Highway and The Youngs: The Brothers Who Built AC/DC, spoke almost daily with Navia for three years while working on this book, and his research is extensive — the bibliography and endnotes run to almost 50 pages.

While there are descriptions of life among the cartels during their blood-soaked heyday — such as the wanton violence, corrupt police and government officials, and extensive control of drug trade — the result is still the tale of a man born with an opportunity to make a good, legal life opting for an illegal fortune based on misery and death.

Chris Smith is a Winnipeg writer.