Satellite tech helped nab Quebec burglar on the lam

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/04/2023 (981 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When we think of the countless and effortless ways we communicate with each other as a species, there is often a taken-for-grantedness in the global satellite networks that allows us to instantaneously text, take part in a video conference or send a large file to a distant part of the planet.

But not too long ago, communicating to another continent was next to impossible, international broadcasts merely science fiction. Surfacing the historical significance of the advent of global communication satellites, freelance author Andrew Amelinckx connects two unique events in the 1960s which intersected to bring a high-profile thief to justice and usher in a new era of human communication.

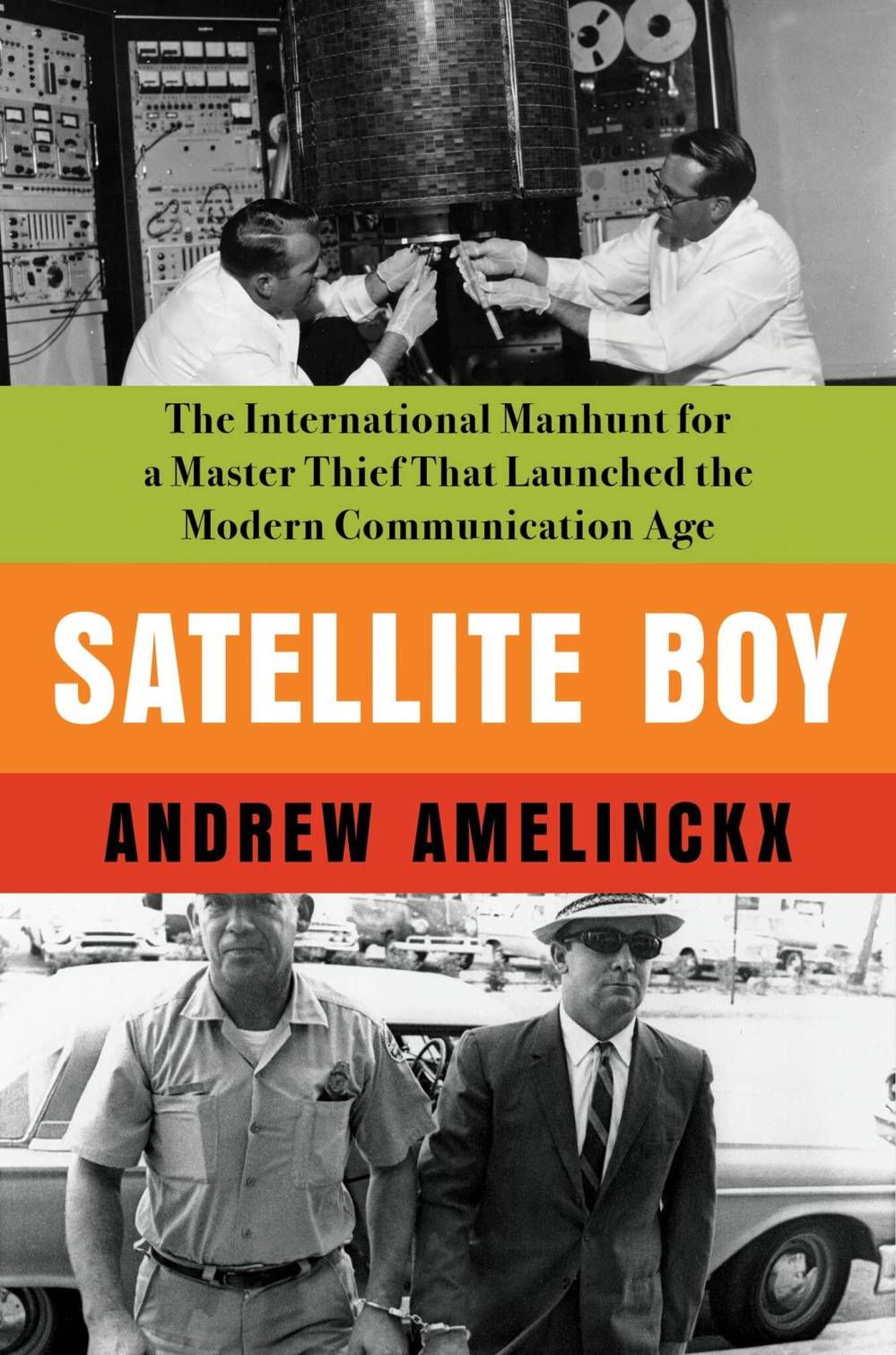

In Satellite Boy: The International Manhunt for a Master Thief that Launched the Modern Communication Age, Amelinckx intersects two seemingly unrelated men in the 1960s — a period of time he qualifies as a decade when “An electric current ran through North America” and “a time when anything seemed possible…”

Satellite Boy

The first principal character was Québécois George Lemay, a handsome Bond-esque character who made his fortunes robbing Montreal banks — institutions that acted as sieves prior to the 1970s. The other was Harold Rosen, an American engineer who worked for Howard Hughes’ aerospace company who would invent the first geosynchronous satellite and whose work would eventually help create Tesla and over 150 other communication satellites.

Amelinckx argues it was this intense time of innovation that not only led Lemay to be recognized as one of the most mysterious burglars on the planet, but also brought on the global communications revolution as part of the space race.

Rosen’s development of the Early Bird satellite series connected the two men, unbeknownst to the pair: “Though they never met, their energies coursed paths, came together, and gave rise to the modern communication age, forever changing the world.”

Following Lemay’s audacious break-in and robbery of the Bank of Nova Scotia in Montreal in 1961, an international manhunt ensued for Lemay, who made off with millions of dollars of private citizens’ and mob money. Hiding in plain sight in Florida, Lemay oozed a prototypical ’60s look: slim suit, skinny tie, sunglasses and a cigarette dangling from his lip. Given the lack of international communication, he was essentially able to hang out in south Florida on his yacht — virtually anonymous.

But the long arm of justice was creeping across the continent.

In California, Rosen was attempting to design and build the first geosynchronous satellite — a satellite that would orbit the Earth in a fixed position over the equator so that 24-hour communication could be maintained. Through various failed prototypes, frustrations finding funding and competition from other communication and aerospace companies, Rosen finally engineered Syncom 3 — a satellite that would broadcast the Tokyo Olympics in the fall of 1964, the first time televised images from one side of the planet were viewed live on another.

For Amelinckx, what it means to be human fundamentally changed on that day.

And as the satellite technology advanced, Lemay’s ability to remain camped out on his yacht in Florida undisturbed flitted away. Early Bird, the next-generation satellite, would host a global broadcast jointly organized by CBS, BBC and the CBC. Each network was able to provide a number of most-wanted images on the broadcast. The RCMP chose Lemay.

Soon enough, Lemay was spotted by private citizens, and landed in a Miami jail. Following an outrageous breakout and further capture years later in Las Vegas, Lemay would find his day in a Montreal court and would serve his time in prison. His dramatic life would fizzle out with a few more failed capers.

Despite Lemay’s demise, Satellite Boy is a fascinating platform and methodology for examining historical significance and cause consequence — two of the six historical thinking skills educators attempt to sear into the minds of young learners. These two individuals, both brilliant and daring in their own minds, tell the story of a specific period of time — one that saw the quest of justice, the divisions of nationalism, the terror of nuclear destruction and the summer of love.

Amelinckx’s storytelling is a compelling way to help us make connections to historical events, allowing the reader into the political and social zeitgeist and to take stock of the possibilities of our species in dark times.

Matt Henderson is assistant superintendent at Seven Oaks School Division.