Inuit translator’s life vividly captured

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/06/2023 (885 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

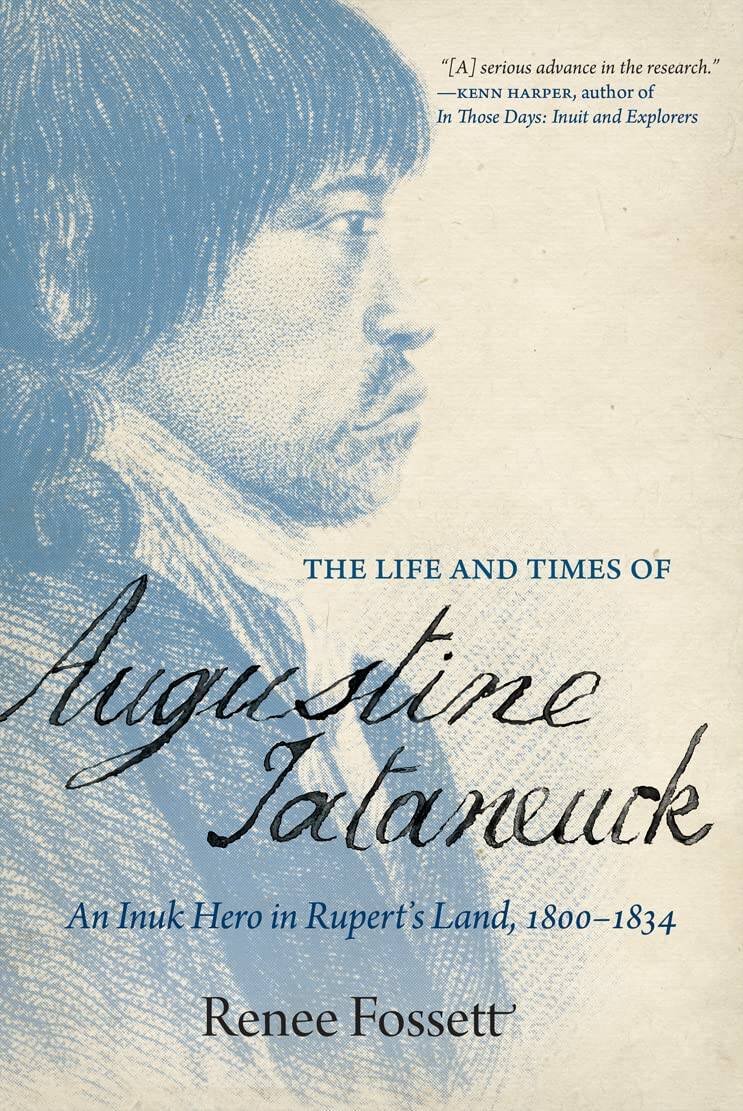

In 1812 a group of nine Inuit men from Hudson Bay’s west coast came to Churchill to trade their winter furs, with one of them leaving his son behind to work for the Hudson’s Bay Company for a year. This arrangement was not unusual and had mutual benefits for the Inuit, who were often fighting for survival, and for the company, which needed to secure its ties to Indigenous traders.

In the end, however, the life of this particular young man, recorded in the HBC records as Augustine Tataneuck, did become exceptional. By 1816 he had worked for the HBC off and on for four years. He had become fluent in English and had proven himself a dependable worker. Thus, when John Franklin asked the HBC for an Inuit interpreter for his first Arctic expedition, Fort Churchill — the only post in contact with the Inuit — suggested Augustine.

To say Franklin’s first search for the Northwest Passage (1819-22) was a disaster is to put it mildly. It was an overland venture, via the Coppermine River, to the Arctic coast, followed by an attempt to explore and map the coast while travelling by canoe. Half the expedition of 22 died of starvation. However, both Franklin and Augustine survived, and Franklin requested Augustine as interpreter for his next venture, via the Mackenzie River (1824-27).

The Life and Times of Augustine Tataneuck

The second expedition was a success. It was carefully planned, and Augustine’s role as interpreter and negotiator became essential. The explorers encountered Inuit groups that far outnumbered them and were not satisfied with a few gifts. Again and again Augustine’s skills and wise advice saved the day.

Author Renee Fossett, a former professor at the University of Winnipeg, lived in the Arctic for 10 years before completing her PhD at the University of Manitoba. She won a Canadian Historical Association prize for a previous book, In Order to Live Untroubled: Inuit of the Central Arctic 1550-1940.

Although the details of Tataneuck’s life are sparse, Fossett has done a formidable job of assembling them from HBC reports and the published journals of Franklin and his colleagues. But that is not her only accomplishment. The context here is very rich — the work at the trading posts, the diet, the celebrations, the hardships, all are fascinating. Imagine, for a moment, the labour involved in cutting holes in the ice to soak out the brine from geese salted the previous summer.

How hard and precarious life was then, and how lucky Augustine was to simply grow up and be able to provide for his own children throughout his adventures. Although one of his bosses reported he was arrogant and another criticized his drinking, most found him knowledgeable, hard-working, loyal and congenial. During two long winters with Franklin, Augustine learned to read and write.

Tataneuck’s adventures did not end with the successful Mackenzie expedition. Accompanied by his wife and youngest child, he was sent to Ungava Bay to help set up the first HBC post in the eastern Arctic. Then, in 1833, he travelled west to assist the Royal Navy in yet another Arctic expedition.

After reaching Great Slave Lake, despite bad weather Augustine insisted on pushing north to Great Bear Lake, where he was to meet other members of a search party. He died along the way in February 1834. By that time he had accumulated so much credit with the HBC that his wife and children were able to draw on his account for the next 20 years.

Faith Johnston’s only northern experience has been two trips to Churchill, but each one was a revelation.

History

Updated on Saturday, June 10, 2023 10:27 AM CDT: Minor copy edit