Stolen in plain sight

Account of world’s most famous art burglar told in riveting detail

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/08/2023 (814 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Good writing is like a full bladder. It gets your undivided attention.

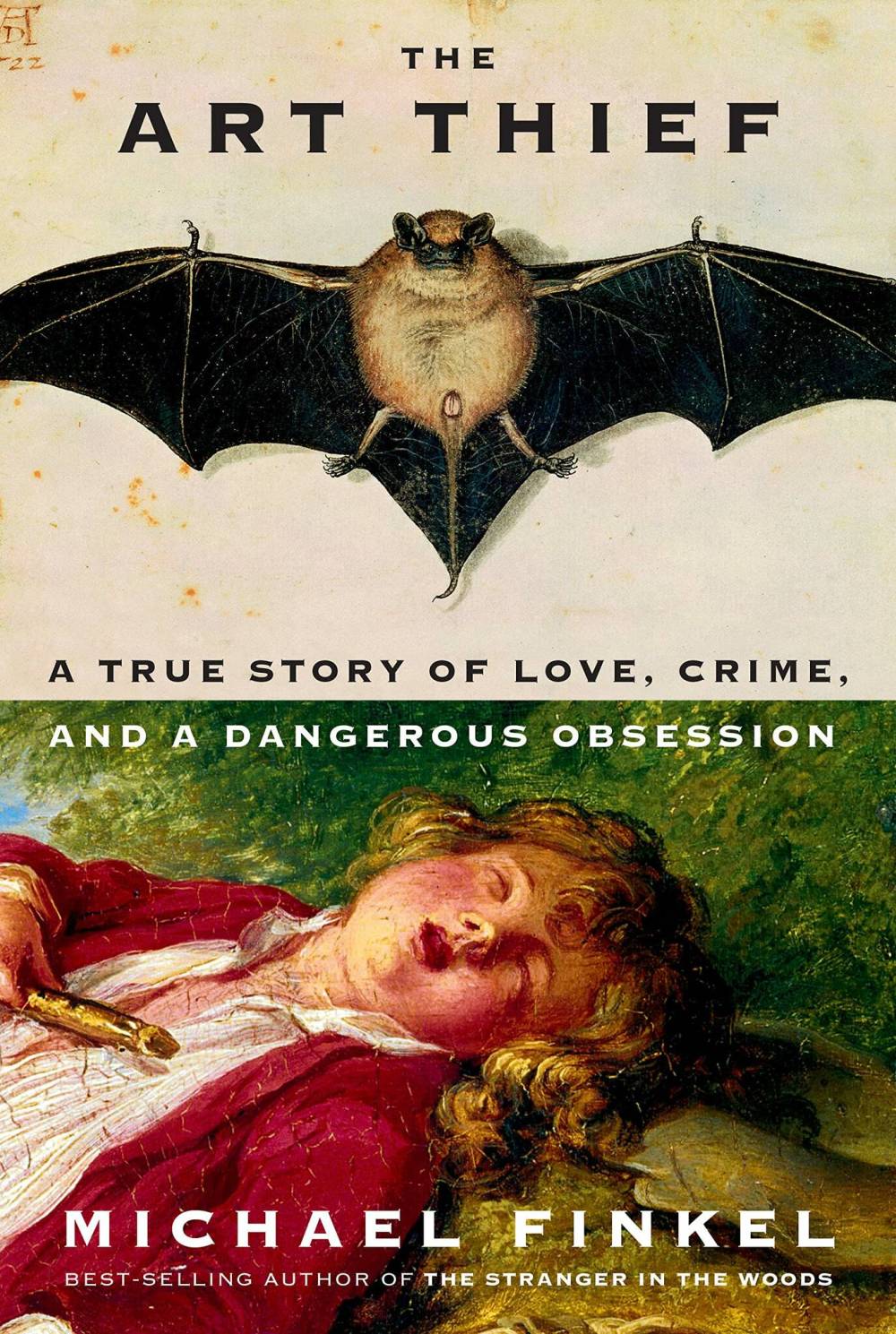

And Stéphane Breitwieser’s wacky life of crime achieves that very focus as author Michael Finkel sketches, in rousing words, what it’s like to have been the world’s greatest-ever art thief, a Houdini of heists who made stealing in very public places appear as matter of fact and doable as walking unmolested out the Tower of London with the British crown jewels in your arms.

As Finkel reveals in The Art Thief, taking somebody else’s property, for Breitwieser, was as much an art form as the paintings, antiquities, tapestry, carvings and other artifacts he stole. He always acted with aplomb — inoffensive, comfortable, unrushed and undistinguished in his robberies — so he would be as anonymous as the law-abiding visitors around him. And his lookout, his then-girlfriend Anne-Catherine Kleinklauss, was equally masterful. On the hunt both were as placid as a bowl of goldfish, even if it was daylight in a crowded picture gallery.

Supplied photo

This portrait of Sibylle of Cleves by Lucas Cranach the Elder, painted circa 1540, was stolen by Stéphane Breitwieser from the New Castle in Baden-Baden, Germany in 1995.

Author Michael Finkel lives in northern Utah. He had the luxury of exhaustively interviewing Breitwieser for The Art Thief. His last book, The Stranger in the Woods, was a bestseller.

As Finkel relates, Breitwieser and Kleinklauss started stealing in the mid-1990s when Breitwieser was in his early 20s. Before he was arrested in 2001, he had criss-crossed Europe to drop into 172 museums, cathedrals and art houses and, with Kleinklauss acting as a brilliant lookout, steal 239 works of art and other exhibits valued at about US$2 billion. One painting alone, Sybille, Princess of Cleves by Lucas Cranach the Elder, was worth over US$8 million.

Astonishingly, if his haul is averaged out during his seven-year crime spree, Breitwieser stole some piece of art every 10.6 days. If there were to be a Stanley Cup for art thieves, Stéphane’s name would be all over it. Among connoisseurs of crime, his name pops up more often than Kleenex. He was also in excellent condition, with a strategic mind that could think its way through a great many security systems.

Breitwieser was so unmemorable in public that he could have been the perfect extra in anybody’s movie. Finkel quotes the Swiss psychotherapist Michel Schmidt: “An extraordinary thing about Stéphane… is that he is so ordinary he can go unnoticed.”

In many ways Breitwieser was a modern example of those stereotypical people created on canvas by American painter Norman Rockwell so long ago — nondescript, reliable and pensive, an image of harmony, not harm.

Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels

Breitwieser stole this 18th-century silver figure of a warship from the Art and History Museum in Brussels, Belgium.

However, explains Finkel, the most astonishing thing about Breitwieser was he never tried to sell these stolen treasures, but rather stored them at his mom’s house in France. He had turned the whole attic into two furnished rooms. That way he and Kleinklauss could climb up, jump into bed and, among other things, lie back and savour the art encircling them. It was Stéphane’s unique layaway plan and it hadn’t cost him a cent. Says Finkel: “They lived inside a treasure chest.”

Finkel elaborates that both Breitwieser and Kleinklauss “are natural thieves, attuned to risk, uncommonly calm. Some of their achievement, though, is true to an uncomfortable truth: many regional museums rely for security, to a shocking degree, on public trust.”

As Finkel puts it, Breitwieser and Kleinklauss are complementary opposites. “He tends to be laser focused; she takes in the whole scene. This yin and yang is central to their stealing prowess.”

Finkel explains that the late German psychoanalyst Werner Muensterberger concludes that unhealthy collecting “takes over one’s life, arising most commonly in people prone to depression who feel out of place in society… and offers these outcasts a magical escape into a remote and private world.”

It is in Brussels, at one of the largest museums in Europe — the Art and History Museum — that Breitwieser commits what he feels is as close to the perfect crime.

Supplied photo

Breitwieser hid most of the stolen artwork his mother’s attic in Mulhouse, France.

Breitwieser’s priorities are as follows: oil paint, silver, ivory. And before him, in a case, is the unsurpassed work of master silversmiths, described as the 16th-century equivalent of Fabergé eggs. He takes two priceless chalices and a tankard. However, explains Finkel, when the pair get away, untouched and to their car, he realizes he’s forgotten the lid to one of the pieces. They return, grab the lid and, while there, steal two more chalices.

But, says Finkel, Breitwieser can’t get his mind off that balloon-sized silver ship he passed over because of its size. So both he and Kleinklauss alter their appearance and, two weeks later, return to the Art and History Museum, stealing not only the birthday-balloon-sized silver ship but also a two-foot-tall chalice.

In 1996 and 1997, three police agencies — two in France, one in Switzerland — are gathering mounting evidence about the disappearing art when a similarly described couple end up visiting galleries in Switzerland and France.

When Breitwieser was caught, it could be argued it was simply bad luck. He was in the Richard Wagner Museum in Switzerland, hadn’t been wearing rubber gloves and stole a bugle. Kleinklauss, furious he hadn’t worn gloves, went back the next day so she could remove his fingerprints. Breitwieser was outside the museum and awaiting her return when a police car drove up. He was handcuffed and taken away. His life was pretty well downhill from there.

Breitwieser’s mother, fearing for him, went into the attic and removed everything. When the police arrived the only thing in the attic was the four-poster bed. Much of the loot was never recovered; his mother burned many of the paintings.

Doug Loneman photo

Michael Finkel

Breitwieser got out of jail in 2015. He was 44.

Barry Craig is a retired journalist.